Chapter 4: Listening

4.1 “Can You Hear Me Now?”

Are You a Good Listener?

It seems like an impossible riddle: “You’re driving a bus, and at the first stop, five people get on; at the second stop, two more people get on and three get off; at the next stop, three people get on and two get off; at the next stop, six people get on and four get off; at the next stop, one person gets off. What color are the bus driver’s eyes?”

Most people just get annoyed, since it’s an obvious switcheroo after doing all that math, and they don’t think the answer can be found in the riddle anyway. But maybe one person in 10 will get it. The most interesting scenario is when more than one person gets it, and when the first one says “brown,” the riddler responds “correct,” but when the second one shouts out “blue!,” the riddler also says “correct!” To most listeners, this doesn’t make any sense — but that’s because they aren’t as good at listening as they think they are. They missed the very first word: “you” (the riddle is just asking “What color are your eyes?”).

Riddles aside, the lesson is a valuable one: most people are not as good at listening as they think they are. Research shows that “on the average, people are only about 25 percent effective as listeners.”[1]

Have you had the experience of realizing, midway through a conversation, that you missed a crucial detail in what the other person was saying? Perhaps the conversation was with your boss, and they end by saying, “Okay? So get started on that,” and you hope you can figure out what “that” refers to without having to admit that you weren’t listening. Was it because you just don’t like your boss and can’t be bothered to listen to them, because your brain went on a temporary detour, or because you got lost in the details of what your boss was telling you and had to slow down to sort it out while your boss kept talking? Or maybe you’re just a terrible person? It’s probably not that, although the situation can be a good reminder that listening takes work, and there are a variety of reasons why that work is not always easy.

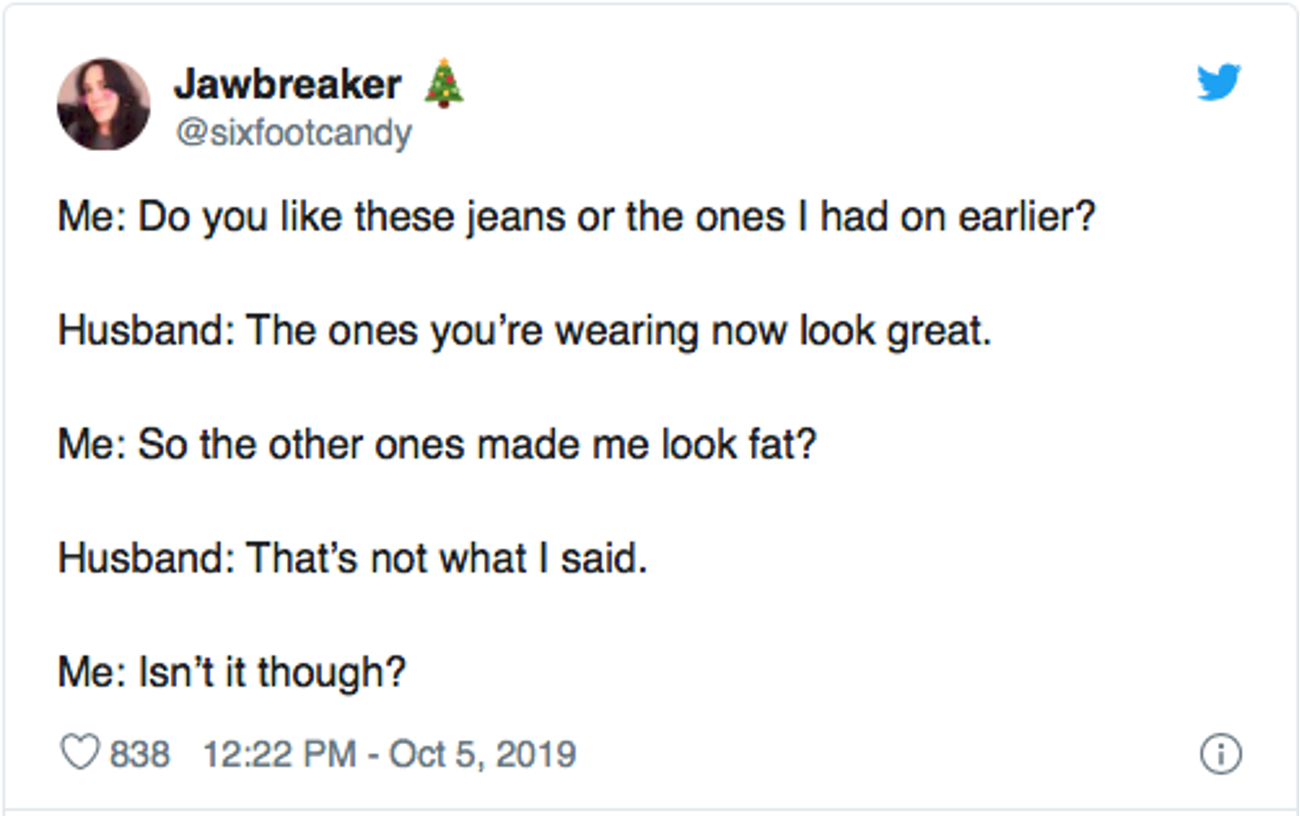

On the other hand, some people put a little too much work into listening, hearing things that the speaker did not say or even imply. I think of a tweet by a person who goes by Jawbreaker, highlighting the perils of a seemingly harmless conversation between married partners:

Some people are eager to finish your sentences, which may seem like a nice gesture unless they get it wrong (which, in my experience, they do at least half the time), and now you have to back up and clarify, “No, what I was going to say was…”.

Many people get frustrated with the poor listening skills of the humans around them, and resort to thinking “At least my dog is a good listener!” (SEE BOX 4.1). And yes, dogs do exhibit some of the helpful listening behaviors we’ll explore below…but I also have to point out a big limitation that pet lovers often willfully ignore: dogs don’t understand English! (Or any other human language — at least, not beyond a few dozen commands). I understand why Chuck (Tom Hanks) so desperately needed a companion to talk to in Cast Away (2000), and I get why he became emotionally attached to Wilson … but even he would have to admit that talking to a volleyball is not really communication. And no, Wilson was not a good listener: “he” was an inanimate object.

If we rank good listeners on a scale of 1 to 10, the good news is that you are better than a volleyball — but probably none of us earns a 10, and those little lapses are useful reminders that we can all do better.

This is a shame, because everything about the communication process ultimately rests on the listener. To put it another way, the whole point of communication is for a listener to absorb what the speaker says, and if that step does not occur, then everything the speaker does to convey a message is pointless.

Picture two recording devices attempting to communicate with each other. The only situation in which they are actually exchanging information is when one is on PLAY and the other is on RECORD. But don’t forget the PAUSE button, which means that nothing is being recorded. In face-to-face conversations, it sometimes looks like people are listening to each other, but in fact each is just waiting for their turn to talk. After the conversation is over, if neither machine was ever on RECORD, nothing happened. Yes, there are times when people express themselves regardless of whether others are listening or not — screaming into a pillow in a moment of frustration, whistling while you work, or repeating something out loud so you remember it — but most of the time, when you communicate, it’s for the purpose of someone else understanding and remembering your message.

I have occasionally heard speakers who seem to lose sight of that simple truth, such as a salesperson who tries to explain a technical product to me but gets going so fast and uses so much esoteric jargon that I get completely lost. In that situation, I often wonder if I should stop them and point out that they are just wasting words, or if I should “humor” them and nod politely. Either way, I’m not getting anything out of the situation, and it doesn’t seem like they are either (unless they like the sound of their own voice, need to kill a little time, or think they have some kind of abstract duty to say things just for the sake of saying them, even if the listener gets nothing out of it).

I’ve also heard academic presentations with the same quality, where the speaker seemed too focused on the esoteric value of just getting the words out, regardless of whether they meant anything to the audience. My favorite example is a dissertation defense where a friend showed up to provide support to the Ph.D. candidate. After the hourlong presentation, the friend said “You seemed really nervous at first, until you hit your stride. Once you started to relax and get into it, I could tell how enthusiastic you were, but I didn’t understand a word you said after that.” It was a charming statement of support, but may have been discouraging to the candidate. I have also tried my hand at judging high school and college debates, but the dizzying speed at which the debaters speak (topping 400 words a minute, roughly three times the normal rate) makes it nearly impossible for me to track 90% of their thoughts. From my perspective, none of those situations count as effective communication.

BOX 4.1: Are Dogs Good Listeners?

This is a question that a number of bloggers have tackled. David Wangel argues that his corgi is a good listener just because the dog isn’t multi-tasking and is fully present: “When you are being present, you don’t have to understand everything that is being said. You can use what you don’t understand as an opportunity to learn more from the other person and help you gain an understanding. Being present is just as much about the journey as it is about the destination.”

Nancy Rones adds that although dogs can’t understand the verbal content of what you are saying, they are pretty good at picking up the emotional tone… and, of course, they maintain confidentiality: “Your deepest secrets and emotional outpourings are safe with your trusty canine companion.”

Liz Scott concurs that dogs are “the best listeners” because of their natural empathy and compassion.

Amy Castro cites a 2010 Associated Press Poll showing that, in the UK, a third of wives and 18% of husbands thought their pet was a better listener than their married partner, and listed a dozen reasons why:

- Pets don’t interrupt.

- Pets don’t take over the conversation.

- Pets don’t judge.

- Pets realize that how you say something is more telling than what you say.

- Pets don’t try to rush you to your point.

- Pets don’t tell you that your feelings are invalid.

- Pets don’t try to top your stories by saying the fish they caught was bigger, their pay raise was higher, or their car is cooler.

- Pets don’t criticize or laugh at your ideas.

- Pets don’t hold grudges when you give them negative feedback.

- Pets don’t let their emotions block what they hear.

- Pets don’t ask a bunch of irrelevant and annoying questions.

- Pets will always keep your secrets.

I can’t help noticing that all 12 of those advantages are things dogs don’t do, and leaves off the things they can’t do. On a personal note, when I was in the process of writing this book, I had many conversations in which I bounced ideas off of other humans, but I never bothered to read a chapter to a dog to get their reactions.

- Burley-Allen, M. (1996). Listening: The forgotten skill (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ↵