Chapter 10: Language

10.1 The Power of Words

Words As Tools

When my son was around a year old, he didn’t enjoy sitting in his high chair. After spending a little time eating, he would squirm until we asked “All done?” In his pre-verbal phase, he would try to convey with gestures that he wanted to get out of that chair. And then came the magical day when he said his first word — actually, a phrase: “Ah duh.” When we realized that “ah duh” meant “all done,” we lifted him out of the chair.

That was the moment he discovered the power of words: all he had to do was make certain sounds with his mouth, and he got what he wanted! As he grew, he made more and more discoveries about how much power words have: if someone was angry at him for something he did, uttering the word “sorry” might change their mood entirely. He was learning what John Austin stated simply in his 1962 book How to Do Things With Words: words don’t only describe things, they accomplish things. Words avoid fights (or start them), provoke emotional reactions (or reduce them), words begin relationships (and end them), and words are the building blocks of rules and laws. If you get a job you enjoy, hope that your boss never utters the words “You’re fired,” because that utterance means your job is over.

As noted in Chapter 1, animals have many channels of communication available to them, but with the exception of parrots and gorillas who have learned sign language, they do not have words. Animals know that the right growl can avoid a fight and the right call can attract a mate, but they don’t have a vocabulary of tens of thousands of words. How many words are at your disposal? If you’re a typical American English speaker, you probably know between 20,000 and 50,000 words.[1]

Even by age three, the average child knows over 3,000 words. If you do the math, that means that even before they begin school, children are learning at least three new words a day, every single day. And a “word” is not a perfect measure of vocabulary size, since so many words have multiple meanings (the word “run,” for example, has 645 different meanings). The good news is, most languages provide a wide variety of ways to express the same thing. This gives rise to the concept of “style,” which here means all of the choices one can make about how to express a single idea.

Imagine this scenario: you walk onto a crowded bus, and all of the seats are taken except one seat with two bags on it, clearly belonging to the woman in the adjacent seat. You would like to sit down, so your goal is to get that woman to move the bags so you can take that seat. What words do you use? You might try “Excuse me, madam — so sorry to bother you, but I’ve had a long day and my legs are hurting so I would really appreciate it if you could possibly move your crap.” Would it work? While you were speaking, the woman looked like she was ready to start picking up the bags — until, that is, you got to the last word. As soon as she heard “crap,” she glared at you and put her hands back on her lap.

Another option would be: “Hey lady, could you quit hogging the seats and move your stuff?” The judicious replacement of “crap” with “stuff” may help, but the terms “lady” and “hogging” do too much damage before you even get to the end of the sentence. You might instead try a simple “Are those your bags?” or dozens of other ways to phrase the request, each with a different chance of success.

Decades ago, a scholar named Richard Weaver noted that some words are particularly powerful, and he used the words “god terms” and “devil terms” to refer to them.[2] This religious-sounding terminology doesn’t imply any connection to actual theology, but does represent how people react to these words. If a god spoke to you, how would you respond? Would you argue, analyze, and debate, or would you blindly obey? Weaver’s point is that certain words provoke a similar response: people don’t argue about them, analyze them, or debate their meaning; they simply respond with automatic obedience.

There are, for example, many dating websites out there, but note how eHarmony distinguishes itself from the competition: by emphasizing that their model is based on “scientific research.” The way they use the word “scientific” indicates that they see it as a god term. What exactly does “scientific” mean here, and what do their scientific methods look like? Few people will ask those questions; most will just think “Okay, scientific: that means it must work.” Since the Federal Trade Commission, the body that regulates advertising in the United States, has no formal definition of “scientific,” there’s no risk of getting in trouble for using the word, and the company can benefit from the assumptions people make about it.

On the other hand, people will automatically respond with revulsion and fear to devil terms such as “censorship.” Does software that prevents children from inadvertently seeing objectionable websites count as censorship? That’s a point reasonable minds could disagree on, but McAfee knows better than to wade into the debate by using the word “censor.” Instead, they feature the word “safe” (such as in an advertisement for their Internet Monitoring Software, where the word “safe” appears no less than six times on one page).

In another example, although you can argue about who is a “freedom fighter” and who is a “terrorist,” there isn’t much debate about whether a “terrorist” is a good thing. If you’re called one, the only appropriate response is to dispute it.

Another way you can recognize a devil term, by the way, is if people are so scared of it that they only use its first initial, as in “the N word” or “the C word” (harking back to the myth that if you say the devil’s name, he will appear, and similar to the fear of saying Voldemort’s name in the Harry Potter universe).

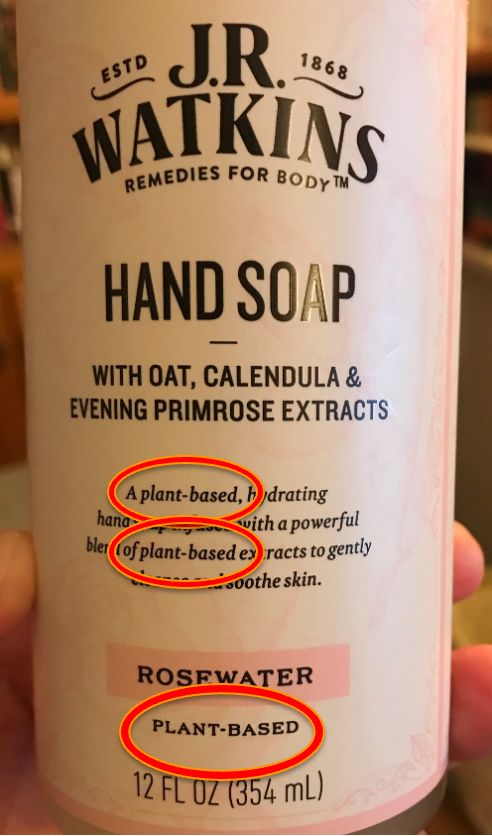

When he introduced this concept in 1953, Weaver had thoughts about what counted as a god term or a devil term, but that was long ago and just one person’s opinion. Today, advertisers and politicians do a great deal of research on people’s reactions to words, and emphasize the god terms heavily while avoiding the devil terms. Someone must have decided that the word “soap” was a devil term at one point, because grocery aisles were full of dozens of varieties of “cleansing bars” and “body wash” without the word “soap” appearing anywhere. But one company that was not afraid to call it soap — J.R Watkins — also relied heavily on a new god term: “plant-based,” using it three times on the front of their bottle.

(With the rise in questions about the potential harms of vaping, some jokesters have wondered if there is a “plant-based” alternative to vapes — like, for instance, cigarettes?).

What is a god term and what is a devil term is also dependent on the audience; you should not assume that everyone responds to words the same way. Beginning with the Black Lives Matter movement in the mid-2010s, the political left considered the term “woke” a god term, representing awareness of systemic discrimination. To the political right, however, it became a devil term, denoting “overrighteous liberalism.” To an elderly audience, “traditional” may be a good thing, while a younger audience might considers it the opposite … unless you call it “old school” or “retro” instead.

- Brysbaert, M., Stevens, M., Mandera, P. & Keuleers, E. (2016) How Many Words Do We Know? Practical Estimates of Vocabulary Size Dependent on Word Definition, the Degree of Language Input and the Participant’s Age. Frontiers in Psychology 7:1116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116 ↵

- Weaver, R. (1953). The Ethics of Rhetoric. Regnery. ↵