Chapter 2: How Communication is Studied

2.5 Qualitative Approaches

Qualitative methods include in-depth interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic research, as well as textual analysis of written and visual messages.

Interviews. What is the difference between a survey and an interview? It’s mostly about depth vs. breadth: a survey is a large collection of very short interviews, whereas an interview is a long survey done with one person. A more stark difference emerges when you look at the results: survey results are usually expressed numerically, but interviews can’t be boiled down to numbers. To put it another way, quantitative researchers like to see graphs; qualitative researchers like to see quotes.

Of course, just as it’s easy to do a bad survey and hard to do a good one, the same applies to interviews. The question of who do you interview is even more crucial when you are talking about only a few interviewees instead of hundreds of survey respondents. Unbiased questions are just as big a concern as they are with surveys, and interview questions can also be open-ended or closed-ended (although, if you’re not a lawyer doing cross examination or a police officer trying to pin down a suspect, most interviewers prefer open-ended questions). Interview guides often stress the importance of establishing rapport with the interviewee — putting them at ease, creating a sense of connection so that the conversation is more open and free-flowing. Whether it’s possible to establish rapport and still be objective is a good philosophical question, and relates to issues such as whether it’s okay for the interviewer to express any opinions of their own.

Focus groups are a form of group interview, but with some advantages. In some cases, you don’t want an interviewee to be influenced by anyone else’s opinions, but in a focus group such influence can be a good thing: people can bounce ideas off each other, and bring up topics that one person might not think of on their own. In a typical focus group, 6–10 respondents are brought together in a room, along with a moderator who asks questions and facilitates a free-flowing discussion for an hour or two. One advantage of a focus group is that it allows you to expose the group to a stimulus of some kind — a new product, a television commercial, a legal case — and get their feedback about it. This is routinely done with full-length movies as well, and may lead the director to change the ending or come up with a new title. If you have the time and money, you can conduct multiple focus groups about the same thing, but it’s usually feasible to conduct only a small number of groups, so you get the views of dozens of people and extrapolate that to the masses. For this reason, choosing representative respondents is crucial.

Ethnographic research involves going out into the world and observing up close, while taking lots of notes on what you observe. The idea derives from anthropologists who studied tribes all over the world, but it can be done in any kind of social environment. When I was first in graduate school, I thought a great model of research would be summarized as “Go out there and experience interesting things, then come back and tell us about it.” Later I discovered the scholarly journal Symbolic Interaction, which is full of such research. A typical issue included studies of war veterans who became antiwar activists, contestants in a reality show, cheerleaders who deal drugs, musicians who collaborate digitally with other musicians they’ve never met, and an examination of prison parolees.

One question that arises in ethnographic research is whether the people you are studying know that you are a researcher. When Margaret Mead went to Samoa in 1926, there was no way she could pass as a Samoan, so her role as a researcher was clear from the start. Other people don’t want to influence the people they are studying, so they keep their status as researchers secret.

One form of ethnographic research is participant observation, in which the researcher is an active participant in the community they are observing. A well-known example is Arlie Hochschild, who wanted to find out what it was like to have to smile for your job all day long, so she got a job as a flight attendant and interviewed many of her co-workers, thus creating a field of research on “emotional labor.” Some research is more autobiographical, such as James Baldwin’s No Name in the Street (1972), recounting his personal experiences during the civil rights movement in America.

Possibly the oldest form of qualitative research is textual analysis (also known as rhetorical analysis) — the detailed examination of texts such as speeches and films. What was Sojourner Truth doing in her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech in 1851? What made Winston Churchill’s speeches great? What are the techniques employed by Greta Thunberg in her address to the United Nations Climate Summit in 2019? Why is the Macintosh computer ad that aired in 1983 considered one of the greatest commercials of all time? What are the underlying messages in Forrest Gump? What gives Taylor Swift songs their power?

What distinguishes textual analysis (a qualitative method) from content analysis (a quantitative method) is that textual analysis is interpretive and typically only focused on one message, whereas content analysis is quantitative and has a broad scope, summarizing hundreds or thousands of messages in the same category. Calling it “interpretive” may imply that textual analysis is free-form and completely subjective, but rhetorical scholars will stress that you have to use a particular method or framework, such as the Burkean Pentad, the Toulmin Model, or Standpoint Theory.

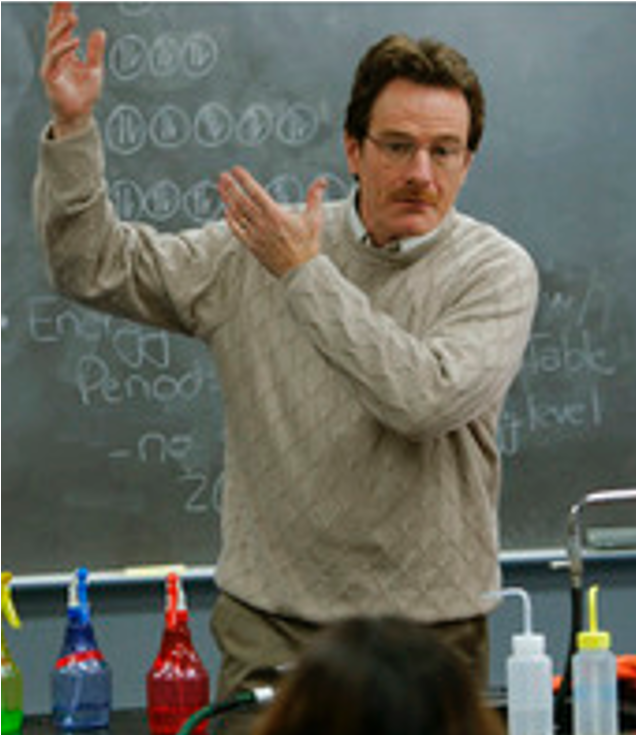

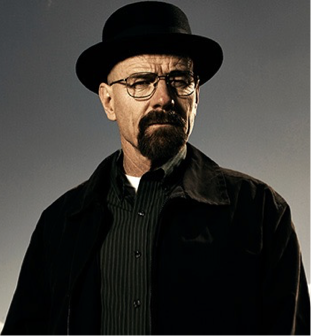

One form of textual analysis is semiotics, the study of visual codes and symbols in particular cultures. Why do so many commercials feature images of a woman staring at a man? What are the visual codes that tell us to love the Na’vi and hate Colonel Quaritch in Avatar? Why are so many Disney villains thin? Why are funeral homes designed the way they are? One of my personal favorites is the visual codes used in the television series Breaking Bad, which is about the transformation of a nerdy high school teacher into a ruthless drug lord.

All of these forms of research are based on different assumptions, habits, and values, yet they all count as “studying communication,” and they all contribute to our understanding of this vast domain of experience. And as with everything else to do with communication, some form of these methods can be done by anyone, whether they studied them formally or not, but taking the time to learn how to utilize them properly is worth the trouble.

BOX 2.5 What does “Square One” look like?

I don’t know if I’m jealous of Louise Banks or not. I enjoy the luxury of teaching communication classes to students with whom I share a baseline of common knowledge; although roughly 10–15% of my students hail from countries on the other side of the world, I get to lecture in my own language and mention things like COVID, artificial intelligence, and Zoom, knowing my students get those references. I can also use terms like “square one” and assume they know what that means or are able to look it up (or if I say that the phrase “square one” comes from board games, they know what a board game is). Even if I were to find myself in Laos or Cote D’Ivoire, I’m sure I could find ways to communicate at least rudimentary concepts with the locals, since human travelers have, for thousands of years, found techniques to communicate with people who don’t share their language.

What I have never had to do was test my communication skills by trying to have a conversation with a creature with whom I have no common baseline at all — not a single word, gesture, visual symbol, or shared experience. But Louise Banks (Amy Adams) is recruited to do just that in the 2016 film Arrival. It is, obviously, a film written by human beings who had to imagine what first contact with aliens would be like, as opposed to an actual first encounter with true aliens, but it is a very useful exercise in figuring out where “square one” really is.[1]

Long before the movie was made, real life scientists were trying to figure out how to communicate with aliens who might intercept messages from humans. In 1977, two Voyager probes were sent into space; one carried a golden record designed by astronomer Carl Sagan and a team from Cornell University. They spent a year deciding what to put on this disc, finally including photographs, diagrams, written messages, and audio recordings of music, nature sounds, and human speech (greetings in 55 languages and a message from U.N. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim). Sagan said “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced space-faring civilizations in interstellar space, but the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet.” Sagan is not clear about whether we are “saying something very hopeful” to each other, or to potential recipients in the constellation Camelopardalis, which it will approach in 40,000 years, but if it’s the former, the target audience is actually us, not aliens. And though very smart people worked on this challenge for a long time, you can’t help but wonder why they included the Latin phrase “Per aspera ad astra” in Morse code, considering how few people on this planet can decipher Morse code or Latin. Even teaching those potential aliens how to play the disc relies heavily on an enormous number of assumptions and shared knowledge. There are two potential take-away messages from this:

- Communicating remotely with a non-earth species is impossible.

- Square One is farther back than most of us can imagine.

So in Arrival, when 12 extraterrestrial spacecraft park themselves around the world, one of the first questions world leaders face is: who should we recruit to try to communicate with them? Call a linguist! They could have involved someone from Communication Studies, or any of the numerous related academic disciplines mentioned in this chapter. But linguist Louise Banks is the right call, largely because she knows that the army’s view of communicating with extraterrestrials is hopelessly naive. They want to rush straight to asking about the aliens’ intentions, but she recognizes why you can’t just jump to asking “What is your purpose on Earth?” There are an awful lot of fundamentals that need to be established first, as she explains:

First, we need to make sure that they understand what a question is: the nature of a request for information, along with a response. Then we need to clarify the difference between a specific you and a collective you, because we don’t want to know why Joe Alien is here, we want to know why they all landed. And purpose requires an understanding of intent. We need to find out, do they make conscious choices or is their motivation so instinctive that they don’t understand a “why” question at all. And biggest of all, we need to have enough vocabulary with them that we understand their answer.

Those are huge questions that even someone who has been teaching communication courses for years can’t begin to answer. Still, I have been tempted to make the movie required viewing for my students, because it is perhaps the best exploration of the fundamental nature of communication I’ve ever seen. And when Louise and the aliens form enough common ground for the aliens to say “offer weapon,” she’s smart enough to figure out that “weapon” means “tool” or “gift.” And what is the gift these aliens came to give us? A new language.

- This film is just one of many that pondered the same “where to begin” question, but in most of the other movies (Contact, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Starman), the alien race had either been to earth before or took the initiative to make it easy for us humans. In other films, the aliens are hostile and have no desire to communicate (A Quiet Place, Independence Day, Signs). ↵