Chapter 16: Group Communication & Decision-Making

16.5 When Decision-Making Goes Wrong

It was a nice moment: they made the decision in two minutes and told the world that the team is now The Great Prunes. Except…. It bothers Fay a little that no actual vote was taken. She didn’t want to look like a stick-in-the-mud by insisting on a formal procedure after that name “popped out” and got such a great reaction, so she figured she was probably the only one who wasn’t sure about it. Meanwhile, Willem thought that nobody else would catch that obscure movie reference and wasn’t crazy about being named after a dried fruit — but he didn’t speak up, either, because everyone else seemed happy about the name. And it turns out that even Mack didn’t intend to propose it as a team name; he just wanted to mention that he liked that line from the movie, and Dave took it and ran with it. In other words, it seemed like there was consensus among the whole team, but there wasn’t.

Management professor Jerry Harvey would say that the group had “driven to Abilene.”[1] He coined the term Abilene Paradox, based on an incident with his family in which they took a 106-mile trip that, it turned out, no one in the family actually wanted to make. The core problem is that people in the group are acting based on what they assume other people want, and no one is clearly stating what they want.

On the quidditch team, this is what happened with Troy and his partner Lacy last Friday, when he came home exhausted and wishing to just spend the night on the couch. But when Lacy came home, Troy could see that she had had a rough week too, and he knew that she liked to relieve stress by dancing. So Troy said “Want to go out to a club?” (secretly hoping she’d say no). When Lacy heard that, she thought to herself “Not really — I’d rather stay home, but he’s so sweet, and it sounds like he really wants to go out, so sure, I guess I can do that.” But out loud she said a cheerful “Sure,” and off they went. All evening long, both of them were just waiting for the other to say it was time to go home, which neither of them did until after midnight. If either one had ever uttered the phrase “I’d rather stay home,” the night out would not have happened — but each was afraid that it would spoil the fun for the other one.

So when other members of the team didn’t express any reservations about the Great Prunes before Nola went off and posted it on social media, was it because they didn’t want to spoil the fun of the moment? Perhaps, or it may have been something even more serious.

In groupthink situations, members are actually afraid to speak up, and those that do are often attacked for it. Irving Janis (one of the developers of the 5-step persuasion model from Chapter 6) analyzed a number of cases of political disasters in which groups of smart people made disastrously bad decisions in the name of preserving the cohesion of the group. Groups in groupthink mode tend to:

- Overestimate their moral superiority (of course we’re the “good team,” so nothing bad can happen to us) and underestimate the opposition, often demonizing or mocking them.

- Put too much faith in their leader, assuming that whatever ideas the leader comes up with must be brilliant.

- Ignore red flags, warnings, and alternatives: they decide on a course of action and don’t listen to any “naysayers” who express doubts or raise objections

- Stress loyalty above all else, and attack doubters for being disloyal. If one or two people get pilloried for speaking up, everyone else in the group who has doubts keeps their mouth shut to protect themselves.

- Impose unnecessary and unrealistic deadlines, and play the “time-shift game.” The game goes like this: if someone suggests that maybe they should take the time to consider the wisdom of an action the leader wants to perform, the response is “This is the time for urgent action; we can talk about it later.” But later when people ask “Now can we talk about it?,” the response is “What’s the point now? What’s done is done.”

The 2017 Fyre Festival seemed to exhibit all those symptoms. The music festival ended so disastrously that it resulted in eight lawsuits from frustrated concert-goers and the organizer Billy McFarland going to prison for four years for fraud. Watch the documentaries Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened or Fyre Fraud and decide for yourself if all five groupthink symptoms were present.

Groupthink doesn’t only happen in high profile cases. As a teacher, I’ve seen classroom project groups exhibit at least some of those symptoms, and several times I’ve heard students admit after the fact that they knew the project was turning into a trainwreck. This raises the question: why didn’t they speak up to prevent that trainwreck?

That question puts the onus on the doubters to say something, and in general it’s a good principle of group functioning that people should speak their minds. But there are other ways of looking at the same situation, and alternative questions one could ask. Why don’t group leaders, for example, check in and make sure they know what their members are thinking? Something like a secret ballot or anonymous survey can reveal things that people may be reluctant to say out loud.

On a more general level, a different phrasing of the question is: “What are the reasons people don’t express their views in groups?” The climate of the group might be intimidating, or members might come from cultures in which speaking up is not the norm [See Chapter 15]. And hidden agendas give members reasons not to speak their mind. At the least, group leaders should not assume they know what everyone is thinking just because no one expresses any objections, and should understand that consensus is sometimes an illusion. It takes work to find out people’s opinions, and being aware of the reasons people don’t speak up can be very valuable.

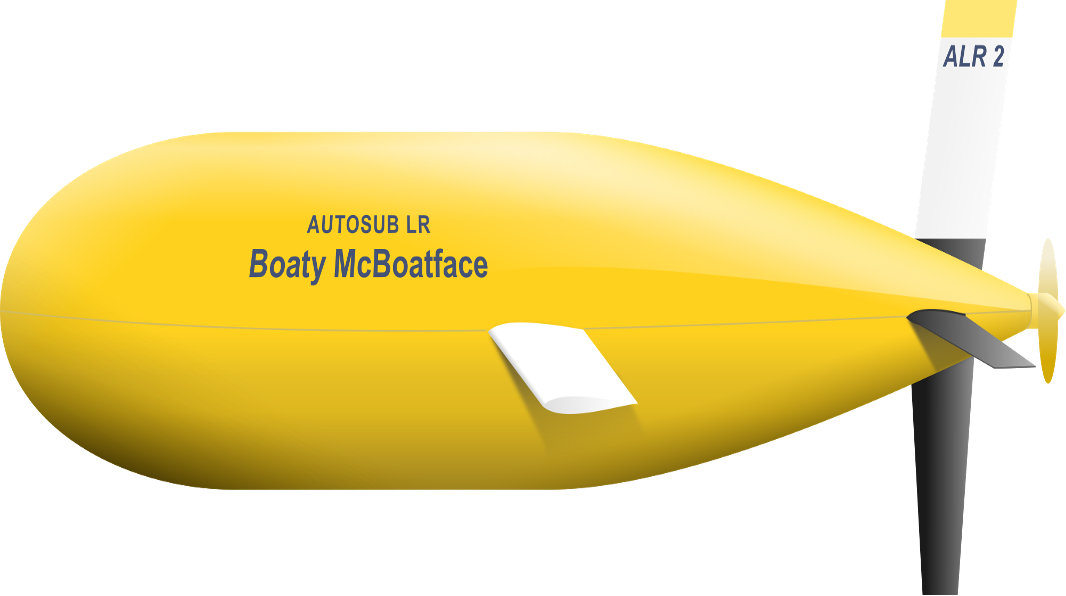

On the other hand, it can be deadly for leadership to gather opinions from group members and then not do anything with that information. My favorite example comes from 2016, when the British National Environment Research Council (NERC) spent £200 million to build a research vessel, and then told the public they wanted their input on what to name it. The top choice was “Boaty McBoatface,” earning 124,109 votes, nearly twice as many votes as all the other suggestions combined. This left NERC with the choice: honor the public opinion poll, or make their own decision? They just couldn’t see writing that name on the side of an expensive ship, so they opted for “RSS Sir David Attenborough” instead…but they did use the voters’ favorite name for a 12-foot autosub.

For some people, the lesson to be drawn here is that people on the internet don’t take polls seriously, but I see this as an example of a much more serious issue that applies to many contexts. With “empowerment” being a popular buzzword these days, many group leaders make a good show of sharing power with others. If that takes the form of asking members (or the public) for their input on decisions, it raises a question that the leaders may not have thought through: “What will you do if you don’t like that input?” They may just think, “Well, if we don’t like their ideas, we can just thank them for the suggestions and do what we want to do anyway.” Whenever I hear the phrase “We’ll take that under advisement,” I wonder if it’s a euphemism for “We’ll humor you, but there’s no way we’ll actually surrender decision-making power to you.”

The problem is that people know when their input has been sought, and watch to see what will be done with that input. If the answer, or even perception, is “nothing,” the actual power situation is made clear, which leads to resentment, bitterness, and disengagement. (See the note above about bands that pretend to be democracies but are really dictatorships in disguise). I know many workers who fill out employee engagement surveys every year, only to realize that no one ever does anything with those survey results.

Despite the silly name, the Boaty McBoatface Dilemma is a problem that no leader should ignore: if you’re going to ask for input, you’d better be prepared to actually do something with it, which means surrendering your own power.

One last decision-making problem I have observed comes when a decision is remade several times. Revisiting a decision is a good idea: perhaps it wasn’t a great idea to begin with, or perhaps the circumstances have changed. But if you revisit the same decision more than two or three times, coming up with a different solution every time, the group will never be able to keep track of the final decision. So, for instance, if you have a group that normally meets on Wednesdays at 3 pm, but in the summertime, when people’s schedules are more free, they decide that 2 pm would be easier, but then rethink the decision again and go back to a 3 pm start time, people won’t remember what the latest decision was, and some will just stay home.

If the Great Prunes decide that this isn’t the best name after all, and change it to the Hippogryphs, and then the Wolverines, people will be permanently confused about what their “real” name is. Perhaps they will do what many people did after the musician Prince changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol in 1993: they called him “TAFKAP” (The Artist Formerly Known As Prince) until he changed it back in 1998. You may have done the same with “X” (formerly known as Twitter) or “Max” (formerly known as HBO Max, or was it HBO Now, or HBO Go?). To prevent the quidditch world from referring to your team as “formerly known as the Great Prunes” for the next 10 years, you should put more thought into getting it right the first time.

- Harvey, J. (1988). The Abilene Paradox and Other Meditations on Management. Lexington Books ↵