Chapter 17: Conflict

17.2 A Definition of Conflict, and Why It’s Healthy

Why is conflict inevitable when human beings get together? Is it because there are so many intolerable people in the world that the statistics are stacked against you: the odds of everyone being nice are too low? No, nice people get in conflict too; it’s not something reserved only for jerks. How people express conflict or manage it may differ based on personality, but personality doesn’t explain why conflict arises in the first place.

Defining what conflict is, on the other hand, does show why it must rear its head from time to time. Conflict has four component parts:

- Incompatible goals. I want you to finish your part in that group paper; you have other priorities. I want the thermostat to be set at 72 degrees Fahrenheit; you want it set at 65 degrees. Having different goals isn’t enough to create conflict; if I get on a bus, my goal is to arrive at my destination, and everybody else on the bus has a different destination. That’s not a problem, though, because we’re not interdependent: it makes no difference to me where another passenger gets off, and vice versa.

- Interdependence. Interdependence means our fates are tied together somehow; we will all get the same grade for that term paper, or we have to find a room temperature we can both live with. If you can “agree to disagree,” that means you don’t have the element of interdependence; if you do have it, then letting everyone follow their own path is not an option. This is one of the frustrating aspects of group life, and one reason that students who earn high grades in other courses sometimes struggle with group communication classes: the idea that your grade depends on what someone else does is not always a comfortable one. Occasionally, a student will gripe about doing group projects in college, thinking that that’s not necessary to prepare them for the work world where that sort of thing doesn’t happen. I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but if anything, the interdependence problem is worse in the work world than it is in school; even freelance workers and solo practitioners with no employees still rely on vendors, customers, and allies.

- Perceived interference. This element stems from the previous two — if I want Goal A, you want Goal B, and we are tied to each other, you are in the way of me achieving my goal. If a bus passenger hijacks that bus and won’t let me off at my stop, they are preventing me from getting where I need to go, and I need to do something about it.

- Communication. This is an issue of definition: can it be conflict if it’s not communicated? A person might get angry with someone else about incompatible goals and perceived interference, but they might just “bottle it up” and not express that frustration. We won’t call that conflict. To earn that name, someone has to express the conflict somehow. It doesn’t have to be words — it can be an “evil eye” look or a slammed door — and people have different thresholds for what kind of expression is required to earn the name conflict. I knew of a mild-mannered professor who married into a “vociferous” family, and the first time he went to his in-laws’ house, there were plates flying through the air and people shouting. He was shocked, but his wife said, “Oh no, they’re not fighting; they’re just letting off a little steam.”

Breaking the definition into component parts helps us answer two questions about the nature of conflict. First, why is it inevitable? Because no matter how well people like each other or generally get along, their goals will never be identical. Second, can communication solve all conflicts? I hear people sometimes imply that “opening up a dialogue” is all that’s necessary to work everything out, and this was true for the student group. I would go so far as to say that conflict can’t be resolved without communication (even wars end with agreements and conferences), but that’s different from saying that communication can fix everything.

One key word in element three is “perceived,” and communication is vital in clearing up misperceptions and helping people realize that their goals are not as incompatible as the participants thought. Sometimes, though, they just are incompatible and the interference is real, and no matter how long the dialogue goes on, the conflict won’t be fixed. There are irresolvable conflicts, and maybe Billy quitting the band was the only thing to be done.

Let’s take a metaphor and explore its implications a little further, perhaps to the point where it gets a bit weird, but bear with me. Chapter 16 introduced systems theory, which is based on the metaphor that a group is like a living organism. If that’s true, then what is one thing that all living organisms do?

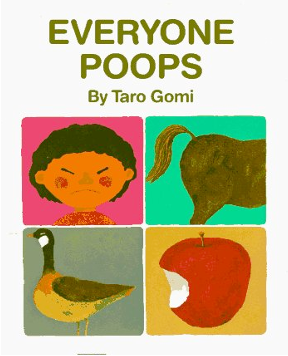

Ask children’s author Taro Gomi:

Let’s use the phrase “excrete waste” instead. When people interact with each other, it can bring up unpleasant thoughts and feelings that must be processed somehow. Following the “excrement” metaphor, there are healthy and unhealthy ways for that to happen. If your attitude is that bodily waste is so unhealthy that you avoid going to the bathroom, things won’t go well for you. On the other hand, the reason most people avoid conflict is because they find it unpleasant and potentially toxic, which is true for bodily waste as well. The point is that finding healthy and productive ways to deal with this part of life is important, and there are consequences if it’s not handled well.

How you think about conflict makes a difference in two ways:

- Your willingness to engage in conflict when it arises. If you think of conflict as inherently unhealthy, you will avoid it at all costs, and perhaps panic when it rears its head. You don’t have to be happy when signs of conflict pop up, but the difference between “Okay, now it’s time to deal with something that needs to be dealt with” vs. “Everything’s fallen apart! Time to end the relationship and head for the hills!” can affect everything.

- Your expectations for success. If you think of conflict as a process with a potentially good outcome, it’s worth putting up with the unpleasantry. If, on the other hand, your belief is that it never ends well, is always harmful, or spells the end of a relationship or group, it won’t be easy to put the energy into it and try to make it work. By the way, that Dublin soul band in The Commitments fell apart after only a few gigs, depriving the world of great music that could have enriched everyone.[1]

Healthy conflict management can have many benefits, including:

- Close examination of issues. It’s easy to float through life without looking at how things are working for everyone. Conflict makes people stop and look closely at whether things are actually working. Before the George Floyd protests in 2020, for instance, many people thought that race relations were at an acceptable point in America and other countries. It took that upheaval to get people to really see what life was like for people of other races, and how systematic racism is perpetuated. And while you may have mixed feelings about lawsuits, one thing that trials do particularly well is examine things very closely. Did you know that when legislators pass new laws, no one tests to see if those laws are constitutional until someone sues and a case rises to the level of the Supreme Court?

- Recognition of difference. Going back to the thermostat example under “Incompatible Goals,” you may have thought, “Someone likes the thermostat set at 65 degrees? Really?” Yes, there are people like that in the world, along with people who have different religious beliefs, attitudes toward guns, definitions of family, and even opinions about how your classroom project ought to be done.

- Overcoming resistance to change. People have a natural resistance to change, some more than others, and sometimes it takes some powerful dynamite to break through that barrier. If you are an American, try this thought experiment: if there had been no American Revolutionary War, would the United States even be a country, or would it still be a British colony?

That said, it’s important to also acknowledge that some conflict is wholly destructive. If your direct experience of conflict has been the toxic or abusive variety, whether it be in the home, in romantic relationships, in groups, or in the workplace, I don’t blame you for not being able to see the positive side of conflict or for having extreme anxiety when it arises. Hopefully you can find resources to help you overcome your past trauma and learn coping strategies.

- That’s the fictional band in the movie. The real-life band that arose from the movie is still going after three decades. ↵