16. Self-inflicted Non-inflammatory Alopecia – Feline

Learning Objectives

- Know! Self-inflicted non-inflammatory alopecia (SNIA) is an alopecia induced by the cat’s licking, chewing/nibbling, hair pulling and/or overgrooming. Consider as differential diagnoses pruritic parasitic disorders (most frequently surface demodicosis); allergic diseases, systemic diseases or psychogenic causes. Make sure to rule out other causes before blaming the cat’s mind if the cat’s history does not indicate a possible psychogenic trigger.

- Know! Because feline SNIA is diagnosed primarily by ruling out other differential diagnoses the following steps are needed in the pursuit of the underlying cause: (i) thorough history and physical examination; (ii) skin scraping, fecal flotation and/or parasiticidal trial to help rule out surface demodicosis, cheyletiellosis and flea infestation; (iii) food elimination trial to pursuit food allergy after other pruritic disorders have been ruled out; (iv) CBC, chemistry profile, and urinalysis if the cat’s history and clinical signs suggest the presence of a systemic disorder or the cat is old at the time the SNIA develops. Identifying the cause for the SNIA can be difficult and frustrating.

- Know! The diagnosis of psychogenic causes triggering SNIA can only be considered after ruling out other possible triggers. However, if the patient’s history highly indicates that SNIA has a psychogenic origin, a possible psychogenic cause can be addressed first.

- Know! The psychogenic origin of SNIA is believed to be a stereotypic behavior disorder. It is believed that endorphins are released during stress situations associated with obsessive grooming behavior and endorphins play an additive reinforcement role maintaining the stereotypic behavior response.

- Know! Many predisposing factors have been associated with the development of stress-related anxiety activities such as breed; the introduction of a new pet, a baby, or visitors into the cat’s environment; moving to a new home or boarding of the animal. Therefore, a thorough history is very important to identify and modify or remove these factors.

- Know! The successful management of SNIA depends on identifying and controlling the triggering factor. Treatment has to be specific to the identified cause. If the cause is psychogenic in origin, the treatment goal is to remove the cat’s desire to obsessively lick, chew/nibble and/or pull out its hair, thus reducing self-trauma. The authors recommend consulting with a behaviorist to delineate the best treatment plan for the patient.

- Remember to tell the owner that it is often difficult to identify the trigger of SNIA and the search for the trigger can be time consuming and expensive. However, determining the cause and specifically treating it increases the chances of resolving the clinical signs and preventing recurrences.

-

General Considerations

- As the name indicates, self-inflicted non-inflammatory alopecia (SNIA) is an alopecic disorder induced by the cat, without causing clinical inflammation. The triggering factors are various, which makes managing this condition challenging.

-

- The owner’s main complaint is typically one or more of the following:

- Excessive grooming, hair pulling, chewing, nibbling or merely hair loss if owners do not witness the cat doing any of these activities.

- The owner’s main complaint is typically one or more of the following:

-

- Excessive grooming, hair pulling and/or skin chewing/nibbling can be a response to itching or a psychogenic cause.

- If history does not strongly suggest a psychogenic cause, do not blame the cat’s mind before ruling out other possible causes.

- Remember, the cat is likely causing the alopecia. Therefore, even if the owner does not see the cat grooming excessively, hair pulling and/or chewing/nibbling, do not rule out the possibility that the cat is the culprit. In these cases, perform a trichogram to show the owner that the hair shaft has been damaged by the cat (e.g. the tip is broken off).

- Excessive grooming, hair pulling and/or skin chewing/nibbling can be a response to itching or a psychogenic cause.

-

- In contrast to dogs with non-inflammatory alopecia where the alopecia develops spontaneously as the result of hormonal disorders (e.g. hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism, alopecia X) or follicular dysplasia, most cases in cats are self-induced and caused by allergies, pruritic parasitic disorders or psychogenic triggers.

Important Facts

- As the name indicates, self-inflicted non-inflammatory alopecia (SNIA) is an alopecic condition induced by the cat as the result of various factors.

- In contrast to dogs with non-inflammatory alopecia where the alopecia develops spontaneously due to hormonal disorders (e.g. hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism, alopecia X) or follicular dysplasia, most cases in cats are self-inflicted and caused by allergies, pruritic parasitic disorders or psychogenic triggers.

-

Cause and Pathogenesis

- SNIA should be considered a multifactorial condition; therefore, it is not a specific disease but the clinical presentation of various disorders. A thorough history is very important in trying to determine the triggering cause. Potential causes associated with this clinical presentation are as follows:

- Parasitic: Be sure to consider surface demodicosis in every cat with SNIA. Surface demodicosis caused by Demodex gatoi is typically a pruritic condition. Perform not only multiple skin scrapings of affected and non-affected areas but also fecal flotation to increase your chances to find mites (remember D. gatoi lives on the skin surface and cats ingest the mites when grooming). Consider also cheyletiellosis as a possible differential if the alopecia is along the dorsum. Significant flea infestation may also result in self-induced alopecia as cats may overgroom to remove the fleas.

- Allergic: A subset of cats presenting with self-inflicted non-inflammatory symmetrical pattern of alopecia will have feline atopic skin syndrome or food allergy. A study showed that most cats with SNIA, in the population investigated by the authors, had food allergy.

- Psychogenic: SNIA can be caused by a stereotypic behavior disorder (anxiety, neurosis) manifesting by incessant grooming, self-licking/chewing/nibbling and hair pulling. HOWEVER, IF THE HISTORY DOES NOT INDICATE A BEHAVIOR CAUSE, MAKE SURE TO RULE OUT ALLERGIC AND/OR PARASITIC CAUSES BEFORE BLAMING THE CAT’S MIND!

- There is a probable relationship between stressful stimuli and the release of adrenocorticotropin hormone and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH), which then cause increase in endorphin production. Endorphins protect the animal from abnormalities associated with chronic stress. However, their narcotic, addictive-like effect may act to reinforce the abnormal grooming behavior.

- Many predisposing factors have been associated with psychogenic causes of SNIA.

- Some cats are temperamentally predisposed, with predilections reported for Siamese and Abyssinian cats.

- Lifestyles of cats may predispose to territorial or psychological stress.

- The introduction of a new pet, a baby, or visitors into the cat’s environment.

- Death of a companion animal or family member.

- Displacement factors, such as moving to a new home, boarding or hospitalization of the animal etc.

- Systemic illness: Be aware that cats with systemic diseases such as hyperthyroidism, hepatic lipidosis, diabetes mellitus, anal sacculitis etc., may develop SNIA because they are not feeling well.

- In some of these cases, the initial stimulus may no longer be present or identifiable, but overgrooming and/or chewing/nibbling have become self-reinforcing.

- SNIA should be considered a multifactorial condition; therefore, it is not a specific disease but the clinical presentation of various disorders. A thorough history is very important in trying to determine the triggering cause. Potential causes associated with this clinical presentation are as follows:

Important Facts

- SNIA is multi-factorial, and a thorough history is very important to determine the triggering cause.

- Potential causes associated with this clinical presentation are pruritic parasitic diseases, allergies, systemic illness, and psychogenic.

- Many predisposing factors have been associated with psychogenic causes such as breed; the introduction of a new pet, a baby, or visitors into the cat’s environment; moving to a new home; boarding of the animal; hospitalization; loss of a close companion etc.

-

Clinical Signs

- The alopecia is localized to areas where the cat can reach. Areas more commonly affected include the forelegs, inner and lateral aspects of thighs, caudal abdomen, and inguinal region. Less commonly, the dorsal lumbar, sacral, or tail regions are involved.

-

- These cats lick/chew/nibble at their skin and/or pull their hair out without inducing any clinical inflammation.

-

- A symmetrical pattern of alopecia is common.

-

- The disease course may be long and progress slowly, sometimes waxing and waning or remaining static for months or years.

- In the Siamese cat, the color of newly grown hairs is changed. They may be darker due to activation of the temperature-labile enzymes that convert melanin precursors to melanin (the skin surface is cooler after the alopecia develops resulting in activation of these enzymes).

Important Facts

- SNIA can be expressed in many ways such as gentle chewing/nibbling, hair pulling, and incessant grooming.

- A symmetrical pattern of alopecia is common.

- Areas that the cat can lick easily are the most affected.

- The disease course may be long and progress slowly, sometimes waxing and waning or remaining static for months or years.

-

Diagnosis

- Identifying the cause of SNIA is often challenging.

- A thorough history and physical examination are essential in trying to identify the inducing cause for the licking, chewing/nibbling and hair pulling behaviors.

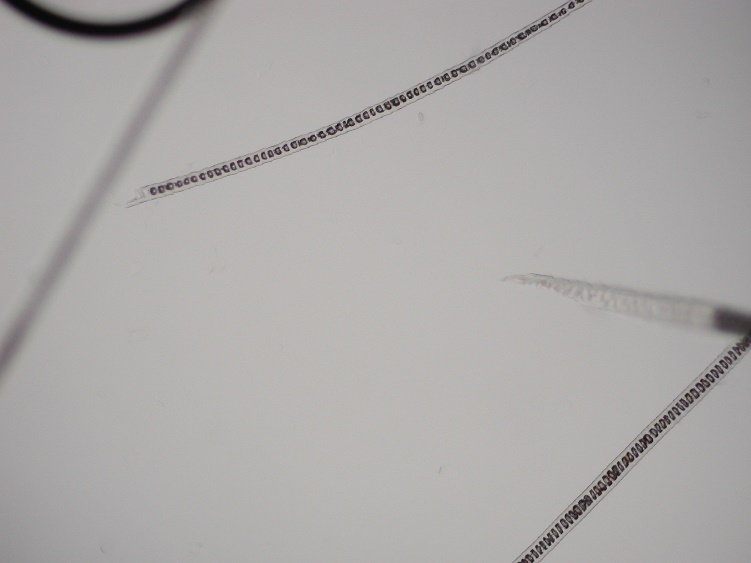

- If there is any question about the self-inflicted nature of the alopecia, a trichogram should be performed to demonstrate broken hair shafts.

-

- Once the self-induced nature of the problem has been confirmed by the history or trichogram findings, start ruling out primary pruritic causes, which would include external parasitic disorders (e.g. surface demodicosis, cheyletiellosis, flea infestation), or allergies (food allergy, feline atopic skin syndrome).

- To identify the specific cause, a complete work-up is necessary.

- Skin scraping, fecal flotation and/or parasiticidal trial should be performed to help rule in/out surface demodicosis and cheyletiellosis. In addition, exam the cat thoroughly for the presence of flea infestation.

- Perform food elimination trials to rule out food allergy.

- A CBC, chemistry profile, and urinalysis should be done if the cat’s history and clinical signs suggest the presence of a systemic disorder and if the cat is old at the time the SNIA develops.

- In some cases, a trial with oral glucocorticoids (e.g. prednisolone) is warranted before pursuing allergic causes. However, it can only be considered in cases where owners witness the cat overgrooming, chewing/nibbling and/or pulling out the hair.

- If a significant response is seen, consider pursuing allergic causes. Make sure to rule out parasitic causes before pursuing a glucocorticoid trial.

- The diagnosis of psychogenic causes for SNIA can only be considered after ruling out other possible triggers as discussed above.

- However, if the patient’s history highly indicates that SNIA has a psychogenic origin, a possible psychogenic cause should be addressed first.

Important Facts

- Identifying the cause of SNIA is often very challenging.

- To identify the specific cause a complete work-up is necessary, which includes (i) skin scraping, fecal flotation and/or parasiticidal trial to help rule in/out surface demodicosis, cheyletiellosis and flea infestation; (2) food elimination trials to rule out food allergy after parasitic causes have been ruled out; (iii) a CBC, chemistry profile, and urinalysis if the cat’s history and clinical signs suggest the presence of a systemic disorder or if the cat is old at the time the SNIA develops.

- The diagnosis of psychogenic causes for SNIA can only be considered after ruling out other possible triggers. However, if the patient’s history highly indicates that SNIA has a psychogenic origin, a possible psychogenic cause should be addressed first.

-

Treatment

- Once the triggering cause has been identified, the treatment will be tailored to the cause. Refer to previous sections in the book for treatment of surface demodicosis, cheyletiellosis, food allergy and feline atopic skin syndrome.

- Remember that systemic diseases or any factors that cause discomfort can trigger some cats to overgroom and cause SNIA.

- If the cause is psychogenic in origin, the goal is to remove the cat’s desire to obsessively lick, chew/nibble and/or pull out its hair, thus reducing self-trauma.

- The authors recommend consulting with a behaviorist to delineate the best treatment plan for the patient. The two approaches to achieving this goal are:

- Identify and modify or remove the initiating stress factor(s).

- Use medical therapy to reduce the cat’s response to the stress factor(s).

- The identification and modification of stress factors require counseling and education of the client.

- The following behavior modification techniques have been recommended for obsessive compulsive grooming:

- Limit exposure to situations that may lead to anxiety.

- Do not pat or talk softly to the cat when it exhibits the behavior because this reinforces the abnormal behavior rather than calms the cat.

- Spend ~10 to 15 minutes daily at a set time playing, grooming and otherwise interacting with the cat.

- Grow an indoor garden of safe plants such as catnip or catmint for the cat to use.

- Provide a variety of toys and alternate or change them weekly.

- Many of the medications used for psychogenic alopecia have potential side effects, require frequent administration and are expensive. The side effects of these drugs can be significant; thus, one must consider the severity of the disease against the possible drug toxicity.

- Medical therapy, in general, have a better chance to work if used in combination with behavior modification programs.

-

Client Education

- The hair loss is induced by the cat.

- Many diseases can trigger the cat to overgroom, pull out the hair, and chew/nibble at the skin and coat and induce SNIA.

- The diagnostic approach can be extensive since it involves ruling out, one at a time, various possible causes (e.g. parasitic, allergic, psychogenic, systemic illness).

- Many of the possible causes are non-curable or the trigger may not be identified; therefore, long-term treatment may be required.

Important Facts

- Once the triggering cause has been identified, the treatment will be tailored to the cause.

- If the cause of SNIA is psychogenic in origin, the goal is to remove the cat’s desire to obsessively lick, chew/nibble and/or pull its skin and/or hairs, thus reducing self-trauma. The two approaches to achieve this goal are: identify and modify or remove the initiating stress factor(s); and use medical therapy to reduce the cat’s response to the stress factor(s) (remember that medications have potential side effects, have to be given frequently and are expensive).

- Owners have to be well educated about this frustrating condition, so they know to expect a long and often expensive process before the triggering factor can be identified and controlled. They also have to understand that despite the methodical search for the trigger of SNIA, not always it can be determined.

References

Buffington CAT. Multimodal environmental modification (MEMO) for prevention and treatment of disease in cats: part 1. Feline Focus 2017; 1; 275-280.

Demontigny-Bedard I, Beauchamp G, Belanger MC et al. Characterization of pica and chewing behaviors in privately owned cats: a case-control study. J Feline Med Surg. 2016; 18: 652-657.

Ellis SL, Rodan I, Carney HC et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219-230.

Herron ME and Buffington CAT. Environmental enrichment for indoor cats: Implementing enrichment – Part2. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2012; E1-E5

Herron ME and Buffington CAT. Environmental enrichment for indoor cats. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2010; 32E1-E5.

Miller WH, Griffin GE, Campbell KL. Muller & Kirk Small Animal Dermatology. 7th edn. St Louis: Elsevier Inc., 2013; 654-657.

McKeever PJ, Nuttall T, Harvey RG. A Color Handbook of Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2nd edn. London: Manson Publishing Ltd., 2009; 66-67.

Mertens P, Torres S, Jessen C. The effects of clomipramine hydrochloride in cats with psychogenic alopecia: a prospective study. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2006; 42:336-343.

Overall KL, Rodan I, Beaver BV et al. Feline behavior guidelines from the American Association of Feline Practitioners. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 227: 70-84.

Overall KL and Dunham AE. Clinical features and outcome in dogs and cats with obsessive-compulsive disorder: 126 cases (1989-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 221: 1445-1452.

Scott, Miller & Griffin. Psychogenic Skin Diseases. In: Small Animal Dermatology. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1995; 845-858.

Seksel K and Lindeman MJ. Use of clomipramine in the treatment of anxiety-related and obsessive-compulsive disorders in cats. Aust Vet J 1998; 76: 317-321.

Sueda KLC. Feline compulsive disorder. Clinician’s Brief 2020; 32-36.

Sueda KLC. Canine compulsive disorder. Clinician;s Brief 2019; 17: 57-62.

Titeux E, Gilbert C, Briand A et al. From feline idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis to feline behavioral ulcerative dermatitis: grooming repetitive behaviors indicators of poor welfare in cats. Front Vet Sci. 2018; 5:81 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00081.

Tynes VV, Sinn L. Abnormal repetitive behaviors in dogs and cats: an approach to behavioral diagnosis in the absence of a “gold standard”. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2014; 44: 543-564.

Waisglass SE, Landsberg GM, Yager JA, et al. Underlying medical conditions in cats with presumed psychogenic alopecia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006; 228:1705-1709.