2.5 Pemphigus Vulgaris

-

General Considerations

- Pemphigus vulgaris is the deep form of pemphigus and considered the most severe of the pemphigus disorders of dogs and cats.

- It is much less common than pemphigus foliaceus.

- It is the erosive/ulcerative form of pemphigus affecting primarily the mucosa and/or mucocutaneous junctions but lesions can also develop on haired skin and rarely on nail folds and nail plates.

Important Facts

- Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare and severe form of pemphigus diagnosed in dogs and cats.

- Lesions are formed deeply in the epidermis and are clinically manifested as deep erosions to ulcerations localized to the mucosa and/or mucocutaneous junctions. Haired skin can also be affected and rarely nail folds and nail plates.

-

Clinical Signs

- Signalment: The information below was taken from a comprehensive review on deep pemphigus disorders.

- German shepherd and German shepherd crossbred dogs were most frequently affected accounting for 17% of the cases.

- Male dogs were slightly more affected than females, in contrast to humans.

- The age of dogs ranged from 8 months to 14 years; mean 6 years and median 7 years. More than 70% of the dogs were at least 5 years old at the time of disease onset.

- Signalment information for cats is based in only four cases. All cats were domestic shorthair. Three of the four were male cats. The median age was 5 years (1 to 14 years).

- Lesions:

- Lesions are deeper than the ones present in pemphigus foliaceus.

- Primary lesions are rare and include flaccid vesicles, and bullae.

- Secondary lesions are common and include deep erosions, shallow ulcers, and crusts. However, ulcers are not formed because histologically the stratum basal of the epidermis is seen attached to the basement membrane. Because the erosions are deep, the clinician cannot differentiate them from shallow ulcers. Erythema, depigmentation, and alopecia are also variably present.

- Pruritus is rare and, when present, it is typically due to a secondary bacterial skin infection.

- Lesions are often painful.

- Secondary systemic signs such as pyrexia, dysphagia, decreased appetite, lymphadenopathy, and depression can be present.

- Lesion distribution:

- Oral mucosa, lips, and nasal planum were reported in 92% of the dogs with pemphigus vulgaris in a comprehensive review on deep pemphigus disease. In this report, all four cats with pemphigus vulgaris had shallow ulcers in the oral cavity, lips and nasal planum.

- The photos below show different views of deep erosions affecting the oral mucosa of a dog with pemphigus vulgaris. These lesions are typically painful and many affected dogs will have ptyalism, as seen in one of the photos.

- Signalment: The information below was taken from a comprehensive review on deep pemphigus disorders.

-

-

- Mucocutaneous junctions including the eyes, mouth, genitalia, scrotum, and anus are typically affected. In a comprehensive review article on deep pemphigus diseases, mucosal or mucocutaneous sites were affected in 93% of the dogs with pemphigus vulgaris cases.

-

-

-

- Nail folds can be affected. Remember! Nail folds are also affected in pemphigus foliaceus in cats (pustular and crusty lesions).

- Ear pinnae, nails, footpads, and axillary and inguinal regions can also be affected. In a comprehensive review of deep pemphigus diseases, 4% (2/50) of the dogs with pemphigus vulgaris only had skin lesions and 4% only had their nails affected.

-

Important Facts

- Primary (i.e. vesicles, bullae) and/or secondary (i.e. deep erosions, crusts) lesions will be present at the mucosal and/or mucocutaneous regions, nails, nail folds, footpads, pinnae, and inguinal and axillary areas.

- Deep erosions will be present at the oral mucosa and lips in about 92% of the cases.

- Animals can become systemically ill and present with dysphagia, decreased appetite, lymphadenopathy, fever, and depression.

-

Diagnosis

- History:

- Disease onset may be sudden or gradual.

- Anorexia and depression may be part of the pet owner’s complaint.

- Clinical signs:

- One or more of the following lesions and body sites: erosions, ulcers, crusts, vesicles, and bullae localized to the mucosa and/or mucocutaneous junctions of oral cavity, pinna, axillary and inguinal regions (other body regions may be affected).

- Nikolsky sign may be positive. It means that the epidermal cohesion is lost enabling the epidermis to be peeled back with a blunt instrument.

- Differential diagnoses:

- Subepidermal blistering dermatoses such as, bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, junctional epidermolysis bullosa, and mucous membrane pemphigoid. Other disorders with oral mucosal ulcerative lesions to consider include erythema multiforme major, severe periodontal disease or oral variants of epitheliotropic T-cell lymphoma.

- Cytology:

- Direct smears prepared from the exudate collected from intact vesicles or bullae (rarely possible because these lesions are transient) or from the exudate obtained from a deep erosion and underneath a crust will reveal typically few acantholytic keratinocytes ± inflammatory cells.

- Histopathology:

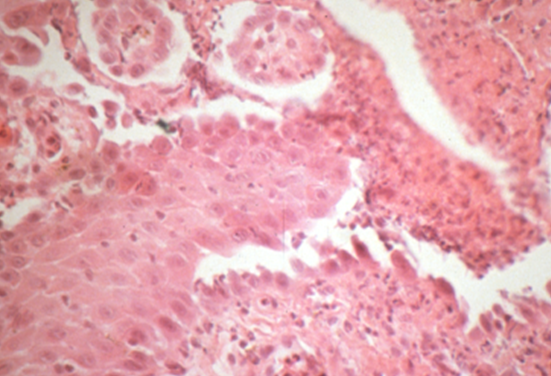

- Suprabasilar acantholysis and clefting of the epidermis and/or mucosae, forming a vesicle or bullae, which contains clear serous fluid. Free floating or rafts of acantholytic cells or inflammatory cells in the vesicle are typically absent. Basal cells detached from the upper epidermis or mucosal epithelium have a “tombstone” appearance. The hair follicle wall may be involved.

- History:

-

-

-

- Depending on the pathologist and biopsy samples, the diagnosis may not be apparent. Biopsy an intact vesicle or bullae if possible. If these lesions are not present, biopsy the inflamed edge of an eroded/ulcerated lesion in addition to the eroded/ulcerated area.

- If possible, send the samples to a pathologist with interest in dermatopathology.

- It is important to send to the pathologist a thorough history, detailed clinical signs, good quality photos, and diagnostic test results if available.

- Contact the pathologist if any questions arise.

- Consider repeating the biopsy to obtain the diagnosis.

-

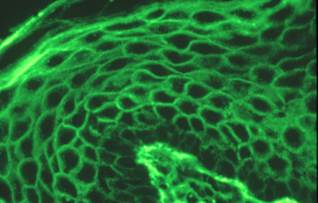

- Direct immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry:

- Direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry show intercellular deposition of immunoglobulins (same pattern seen in pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus erythematosus).

-

-

-

- Remember! Skin biopsy is submitted for these tests. The samples should be fixed in Michel’s fixative for immunofluorescence and 10% formalin for immunohistochemistry.

- False negative results are common.

- Indirect immunofluorescence:

- Same staining pattern obtained with direct immunofluorescence.

- Remember! Serum is the sample submitted for this test.

- It is usually associated with low titer or negative results.

- CBC, chemistry profile, urinalysis:

- Will provide a baseline for monitoring of potential therapeutic side effects.

- Leukocytosis is a common finding due to severe skin inflammation.

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA):

- Negative.

-

Important Facts

- A detailed history and characteristic clinical signs are helpful diagnostic information. Crusts, deep erosions and/or shallow ulcerations affecting primarily the oral cavity and lips are common signs. Flaccid vesicles and/or bullae are rare.

- Cytological exam of direct smear from intact vesicles/bullae or from the exudate present underneath a recent crust or erosion/ulceration typically reveals few acantholytic keratinocytes ± neutrophils.

- Histopathology is the most important diagnostic test and reveals a suprabasilar cleft.

- Direct and indirect immunofluorescence tests are not frequently used as a diagnostic tool because false negative results are common and these tests are not widely available.

- CBC will frequently show leukocytosis due to severe skin inflammation.

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test is negative and not typically performed.

-

Treatment

- Aggressive combination therapy is often required.

- Options of immunosuppressive drugs include one or combination of the following: (See “Therapy for Autoimmune Diseases” for dose and specifics on treatment protocols).

- Glucocorticoids – First line therapy alone or in combination with adjunctive immunosuppressants.

- Azathioprine – Do not use this drug in cats because they develop bone marrow suppression.

- Cyclosporine.

- Chlorambucil.

- Mycophenolate mofetil may be considered as a glucocorticoid sparing agent.

- Gold salts.

-

Prognosis

- The prognosis is poor without therapy and the patient usually dies.

- Guarded to good with therapy. In a comprehensive review paper, complete remission was reported in 65% of dogs that received treatment. Relapses can occur when the dose of immunosuppressants is reduced or the drugs are discontinued.

Important Facts

- The prognosis is poor without therapy and guarded to good with treatment.

- Complete remission was reported in 65%.

- Relapses can occur if the drug dose is reduced or the treatment is discontinued.

References

Dalmau A, Ordeix L. Putative pemphigus-like reaction to oral fluralaner in a dog. Vet Dermatol 2023; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13243.

Bizikova P, Linder KE, Anderson JG. Erosive and ulcerative stomatitis in dogs and cats: which immune-mediated diseases to consider? J Am Vet Med Assoc 2023; doi.org/10.2460/javma.22.12.0573.

Martinez N, McDonald B. and Crowley A. A case report of the beneficial effect of oclacitinib in a dog with pemphigus vulgaris. Vet Dermatol 2022; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13063.

Medleau L, Hnilica KA. Chapter 8. Autoimmune and immune-mediated skin disorders. In: Small Animal Dermatology: A color Atlas and Therapeutic Guide 2006. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders, Missouri, 189-227.

Miller, Griffin and Campbell. Chapter 9. Autoimmune and immune-mediated dermatoses. In: Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology 2013. 7th ed., W.B. Saunders, Missouri; 432-462.

Olivry T. Auto-immune skin disease in animals: time to reclassify and review after 40 years. BMC Vet Res 2018; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1477-1.

Olivry T, Chan LS. Autoimmune blistering dermatoses in domestic animals. Clin Dermatol 2001; 19(6):750-760.

Olivry T., Jackson HA. Diagnosing new autoimmune blistering skin diseases of dogs and cats. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001; 16: 225-229.

Olivry T. Linder KE. Dermatoses affecting desmosomes in animals: a mechanistic review of acantholytic blistering skin diseases. Vet Dermatol 2009; 20: 313-326.

Outerbridge CA, Affolter VK, Lyons LA et al. An unresponsive progressive pustular and crusting dermatitis with acantholysis in nine cats. Vet Dermatol 2017; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12501.

Tham HL, Linder KE, Olivry T. Deep pemphigus (pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans and paraneoplastic pemphigus) in dogs, cats and horses: a comprehensive review. BMC Vet Res 2020; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02677-w.