2.15 Bullous Pemphigoid – Dogs and Cats

-

General Considerations

- Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a rare autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease of dogs and cats.

- In contrast to other autoimmune subepidermal bullous diseases, bullous pemphigoid affects primarily haired skin with no or mild mucosal involvement and typically with no systemic signs.

Important Facts

- Bullous pemphigoid is a rare subepidermal bullous disease of dogs and cats

- Lesions are typically limited to haired skin and if mucosal or mucocutaneous lesions are present, they are mild.

- Systemic signs are usually absent.

-

Clinical Signs

- Signalment: the information is based on nine cases reported in the literature.

- The German shepherd dog and dachshund were the breeds overrepresented in the few reports.

- The reported median age at disease onset was 5 years; range 10 months to 15 years.

- The few reported cases showed that males are affected twice more often than females.

- Lesions:

- Primary lesions are rare and include erythematous macules, erythematous patches or plaques, tense vesicles (blisters), and bullae. These lesions are ephemeral and not seen often.

- Signalment: the information is based on nine cases reported in the literature.

-

-

- Secondary lesions are common because vesicles and bullae rupture easily and are replaced with deep erosions, ulcers, and crusts.

- Pruritus is uncommon.

- Systemic signs including anorexia, fever, and depression are typically absent but may be present in severe cases.

- Pain is variable and correlates with the extent and severity of signs.

- Lesion distribution:

- Haired skin was affected in all reported cases and included mostly the areas of frictions such as axillae, groin, and elbows. The concave pinnae were also often affected. These sites were involved in 56% of the cases.

- Lesions on mucosae and mucocutaneous junctions are typically mild. Areas affected in the report include the lips (56%), tongue (33%), gingivae (22%), nasal planum (22%), eyelids (11%), and plate (11%).

- Footpads, nail folds and perianal/perigenital regions were affected in 22% of the reported cases.

-

Important Facts

- German shepherd dogs and dachshunds were overrepresented in the few reported cases.

- The median age at disease onset was 5 years and males were reported to have the disease twice more often than females.

- Primary lesions such as vesicles, bullae, erythematous macules and patches form initially but they are ephemeral and are replaced by deep erosions and shallow ulcers and crusts.

- All reported cases had lesions on haired skin and especially at sites of friction.

- Mucosal and/or mucocutaneous regions, footpads, nail folds, and perianal and perigenital areas were reported to be less frequently affected but when present the lesions tended to be mild.

- Systemic signs were generally absent on the reported cases but they can be present depending on the extent and severity of clinical signs.

-

Diagnosis

- Differential diagnoses:

- All diseases that cause predominantly vesicles/bullae and deep erosions/ulcers including pemphigus vulgaris, mucocutaneous lupus erythematosus, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, mucous membrane pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and drug reaction.

- A compatible history and characteristic clinical signs are important parts of the diagnostic equation.

- Cytology:

- Direct smears of the exudate collected from intact vesicles or bullae or obtained from an ulcer, deep erosion, or underneath a crust will yield nonspecific findings.

- The test results are nonspecific, but this test is important to investigate the presence of secondary infections

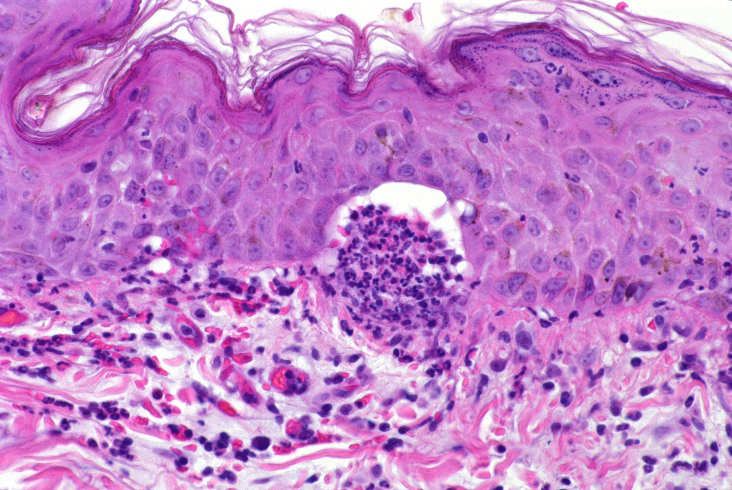

- Histopathology:

- Subepidermal cleft and vesicle with no inflammatory cells or variable numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils. Similar infiltrate can be seen in the superficial dermis.

- Biopsy an intact vesicle/bulla if possible; otherwise, sample the active border of an erosion or ulceration.

- Aim to submit the biopsy samples to a pathologist with interest in dermatohistopatholgy. Make sure to include a detailed history and clinical signs description. If possible, also submit good quality photos.

- Ask the pathologist to perform periodic-acid Schiff (PAS) staining of the sample or immunohistochemistry for collagen IV. The PAS stain will color the lamina densa of the basement membrane zone magenta. In the case of bullous pemphigoid, the floor of the vesicle/bulla should stain magenta. This test result will help differentiate bullous pemphigoid from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita but not from the other autoimmune subepidermal bullous diseases, which also stain the floor of the cleft/vesicle. Keep in mind that the sensitivity of this test is low.

- Subepidermal cleft and vesicle with no inflammatory cells or variable numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils. Similar infiltrate can be seen in the superficial dermis.

- Differential diagnoses:

-

- Direct immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry:

- A linear deposition of immunoglobulins along the basement membrane zone means a positive test but this finding is non-specific.

- Remember! Skin biopsy is submitted for these tests and samples should be fixed in Michel’s fixative for immunofluorescence and formalin for immunohistochemistry.

- False negative results are common.

- Indirect immunofluorescence:

- Same staining pattern obtained with direct immunofluorescence.

- Salt-split canine buccal mucosa tissue is the best substrate and positive results were seen with all tested serum from affected dogs in the report.

- Remember! Serum is the sample submitted for this test.

- Same staining pattern obtained with direct immunofluorescence.

- CBC, chemistry profile, urinalysis:

- Used as baseline for monitoring potential side effects associated with therapy.

- Leukocytosis is a common finding due to severe skin inflammation.

- Direct immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry:

Important Facts

- A detailed history and clinical signs are crucial information to achieve a diagnosis.

- Cytological exam of direct smear from intact vesicles/bullae or from the exudate present underneath a recent crust or from a deep erosion/ulceration reveals nondegenerate neutrophils, mononuclear cells and no acantholytic keratinocytes.

- Histopathology is the most important diagnostic test and reveals a subepidermal cleft and vesicle formation with no or variable numbers of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and eosinophils. Early changes include vacuolar alteration in the basement membrane zone with or without disruption of basal cells.

- Direct and indirect immunofluorescence tests are not frequently used as a diagnostic tool because they are not typically available in commercial laboratories.

-

Treatment

- One or more of the following treatment options is recommended. See “Therapy for Autoimmune Diseases” for dose and specifics on treatment regimens.

- Glucocorticoids.

- Azathioprine (do not use it in cats because they develop bone marrow suppression).

- Chlorambucil.

- Oclacitinib.

- Doxycycline and niacinamide. Practice antibiotic stewardship and try to avoid this treatment modality to prevent bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

- One or more of the following treatment options is recommended. See “Therapy for Autoimmune Diseases” for dose and specifics on treatment regimens.

-

Prognosis

- Prognosis is good if proper therapy is instituted with most cases having partial to complete remission.

References

Bizikova P, Linder KE, Anderson JG. Erosive and ulcerative stomatitis in dogs and cats: which immune-mediated diseases to consider? J Am Vet Med Assoc 2023; doi.org/10.2460/javma.22.12.0573.

Bizikova P, Olivry T, Linder K et al. Spontaneous autoimmune subepidermal blistering diseases in animals: a comprehensive review. BMC Vet Res 2023; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-023-03597-1.

Medleau L, Hnilica KA. Chapter 8. Autoimmune and immune-mediated skin disorders. In: Small Animal Dermatology: A color Atlas and Therapeutic Guide 2006. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders, Missouri, 189-227.

Miller, Griffin and Campbell. Chapter 9. Autoimmune and immune-mediated dermatoses. In: Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology 2013. 7th ed., W.B. Saunders, Missouri; 432-462.

Olivry T. Auto-immune skin disease in animals: time to reclassify and review after 40 years. BMC Vet Res 2018; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1477-1.

Olivry T, Chan LS. Autoimmune blistering dermatoses in domestic animals. Clin Dermatol 2001; 19(6):750-760.

Olivry T., Jackson HA. Diagnosing new autoimmune blistering skin diseases of dogs and cats. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001; 16: 225-229

References

Banovic F, Olivry T, Linder KE. Ciclosporin therapy for canine generalized discoid lupus erythematosus refractory to doxycycline and niacinamide. Vet Dermatol 2014; 25: 483-e-79.

Bizikova P, Linder KE, Olivry T. Immunomapping of desmosomal and nondesmosomal adhesion molecules in healthy canine footpads, haired skin and buccal mucosal epithelia: comparison with canine pemphigus foliaceus serum immunoglobulin G staining patterns. Vet Dermatol 2010; 22:132-142.

Bizikova P. Olivry T, Linder K, et al. Spontaneous autoimmune subepidermal blistering diseases in animals: a comprehensive review. BMC Vet Res 2023; 19:55.

Bryden SL, White SD, Dunston SM et al. Clinical, histopathological and immunological characteristics of exfloiative cutaneous lupus erythematosus in 25 German short-haired pointers. Vet Dermatol 2005; 16:239-252.

Jackson HA. Eleven cases of vesicular cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Shetland sheepdogs and rough collies: clinical management and prognosis. Vet Dermatol 2004; 15:37-41.

Jackson HA. Vesicular cutaneous lupus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2006; 36:251-255.

Harvey RG, Olivri A, Lima T et al. Effective treatment of canine chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus variants with oclacitinib: Seven cases. Vet Dermatol 2022; DOI:10.1111/vde.13128.

Manzuc PJ, Koch SN, Benzoin L, Grandinetti J. Mycophenolate mofetil in the therapy of vesicular cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a case report. Vet Dermatol. 2016; 27(Suppl. 1):87. (abstract).

Martinez N, McDonald B. and Crowley A. A case report of the beneficial effect of oclacitinib in a dog with pemphigus vulgaris. Vet Dermatol 2022; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13063.

Mauldin EA, Morris DO, Brown DC, et al. Exfoliative cutaneous lupus erythematosus in German shorthaired pointer dogs: disease development, progression and evaluation of three immunomodulatory drugs (ciclosporin, hydroxychloroquine, and adalimumab) in a controlled environment. Vet Dermatol 2010; 21(4): 373-382.

Medleau L, Hnilica KA. Chapter 8. Autoimmune and Immune-mediated Skin Disorders. In: Small Animal Dermatology: A color Atlas and Therapeutic Guide. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders, Missouri, 2006; 189-227.

Miller, Griffin and Campbell. Chapter 9. Autoimmune and Immune-mediated Dermatoses. In: Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed., W.B. Saunders, Missouri, 2013; 432-462.

Oberkirchner U, Linder KE, Olivry T. Successful treatment of a novel generalized variant of canine discoid lupus erythematosus with oral hydroxychloroquine. Vet Dermatol 2011; 23: 65-e16.

Olivry T and Chan LS. Autoimmune blistering dermatoses in domestic animals. Clin Dermatol 2001; 19(6):750-760.

Olivry T, Rossi MA, Banovic F, et al. Mucocutaneous lupus erythematosus in dogs (21 cases). Vet Dermatol 2015; 26: 256-e55.

Olivry T, Linder KE and Banovic F. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus in dogs: a comprehensive review. BMC Vet Res 2018; 14:132.

Olivry T et al. Diagnosing new autoimmune blistering skin diseases of dogs and cats. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001; 16(4):225-229.

Rossi MA, Messinger LM, Linder KE, Olivry T. Generalized canine discoid lupus erythematosus responsive to tetracycline and niacinamide. J Anim Hosp Assoc 2015; 51(3): 171-175.,

Tham HL, Olivry T, EL Linder et al. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in dogs: a retrospective study of 16 new cases. Vet Derm 2016; 27: 376-e94.