4.6 Systemic Mycosis – Histoplasmosis – Small Animals

Learning Objectives

- Remember! Histoplasma capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus, which prefers to live in nitrogen-rich organic matter containing bird and bat excrements. In the USA, most cases occur in the central part in the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi River Valleys (same region as Blastomyces organisms).

- Know that the infection occurs via inhalation of the organism and after a lung infection is established, dissemination may occur via blood and lymphatics to become systemic.

- Know that most cases will present with disseminated disease affecting the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract (especially dogs), spleen and liver. Eyes, central nervous system, bone and skin can also be involved but less frequently.

- Know that finding the organisms on cytology or histopathology is the gold standard test.

- Know that the same urine antigen test used for the diagnosis of blastomycosis has shown to have very good sensitivity for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis because these organisms cross react.

- Keep in mind that the AGID antibody test is not reliable because it is associated with many false positive and negative results.

- Learn if routine fungal culture should be performed and explain the rationale.

- Know how do you manage histoplasmosis.

- Learn about the disease prognosis to be able to discuss this issue with your client.

-

Etiology

- Histoplasmosis is caused by Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum.

- It is a dimorphic fungus.

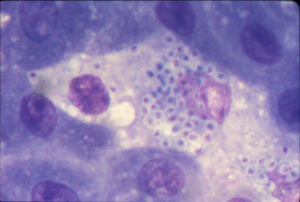

- At body temperature it transforms into a yeast form. The organism is 2 to 4µm in diameter and has a thin cell wall. The white halo commonly present is an artifact and results from the shrinking of the yeast during staining. See photo below.

- The fungal organism is typically seen within macrophages.

-

-

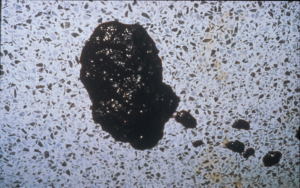

- Histoplasma capsulatum lives in the soil as a mycelium.

-

Important Facts

- Histoplasma capsulatum is an opportunistic dimorphic fungus, which lives in the soil as a mycelium and in the body as a yeast.

-

Geographic Distribution

- Histoplasmosis is endemic in temperate/tropical regions worldwide. In the USA, most cases occur in the central part in the Ohio, Missouri, Tennessee, and Mississippi River Valleys (same region as Blastomyces). It has been also reported in Australia, Japan, Central and Latin America.

- Surveys indicate that most people and canine inhabitants of endemic areas become infected.

- The organism can survive broad temperature variations but prefers areas with warm, moist, humid conditions and soil containing nitrogen-rich organic matter such as bird (e.g. starling) and bat excrements.

Important Facts

- The fungal organisms prefer soil containing nitrogen-rich organic matter such as bird and bat excrements.

- In the USA, most cases occur in the central part in the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi River Valleys (same region as Blastomyces).

-

Natural reservoir and epidemiology

- The organism thrives in nitrogen-rich organic matter such as decaying bird feces and fresh bat excrements. Bats are the primary reservoir of the organism and serve to disseminate the disease geographically as live organisms are present in their gastrointestinal tract and are eliminated through the feces.

- Most affected animals have exposure to the outdoor environment. However, the disease has been reported in animals restricted to the indoors.

-

Pathogenesis

- Infection occurs via inhalation of the organism (microconidia). Within the lungs, the organisms are converted to the yeast form and a local infection is established. However, the infection can disseminate via blood and lymphatics to become systemic.

- Organs rich in the mononuclear phagocyte system such as the liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow are most commonly affected. Other organs such as, skin, eye, bone and central nervous system can also be involved. The disease can be limited to the gastrointestinal tract suggesting that infection may occur via ingestion.

-

Species

- The disease has been reported in dogs, cats and horses. It can potentially affect any species.

-

Signalment and Clinical Signs

- Cats appear to be slightly more susceptible than dogs.

- Dogs and cats of any age can be affected (2 months to > 15 years). Similarly, there are no sex and breed predilections.

- Sporting or working dogs are more susceptible.

- Most cats are FIV negative and co-infection with FLV has been reported in about 16% to 28% of cats with histoplasmosis.

- Nonspecific signs such as fever, weakness, depression, weight loss, anorexia and lymphadenopathy may be present in cats and dogs.

- Specific signs:

- Cats:

- Most cases will have disseminated disease.

- Dyspnea, tachypnea, and abnormal lung sounds occur in more than 50% of the cases.

- Lymphadenomegaly, splenomegaly and hepatomegaly are common.

- Organs less often affected include skin, eye, gastrointestinal tract and bone.

- Skin signs include one or more of the following: nodules, ulcers, sinus tracts and oral mucosal lesions.

- Cats:

-

-

- Dogs:

- Signs of small or large bowel diarrhea is the most common clinical sign in dogs.

- Large bowel: tenesmus, dyschezia, mucous and fresh blood in stools.

- Small bowel: watery diarrhea, melena, and dyschezia.

- Some cases may present with only gastrointestinal disease.

- Signs of small or large bowel diarrhea is the most common clinical sign in dogs.

- Dogs:

-

-

-

-

- Pale mucous membrane because of bone marrow involvement or gastrointestinal blood loss.

- Visceral lymphadenomegaly, hepatomegaly, icterus, ascites and splenomegaly are common signs.

- Dyspnea, cough and abnormal lung sounds – lung signs are more common in cats than dogs.

- Primary pulmonary disease is asymptomatic, often transient, and is recognized in dogs.

- Less common clinical signs include vomiting, peripheral lymphadenomegaly, lameness, ocular disease, cutaneous lesions and central nervous system signs.

-

-

Important Facts

- The disseminated form of the disease affects mainly the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, spleen, visceral lymph nodes and liver.

- The gastrointestinal tract is more often affected in dogs than cats and it can be the only organ affected in dogs.

- Lung signs are more frequent in cats.

- Eyes, central nervous system and bone can also be involved but less commonly.

- Skin is rarely affected and lesions are characterized by nodules, draining sinus, ulcers, and mucosal lesions.

-

Diagnosis

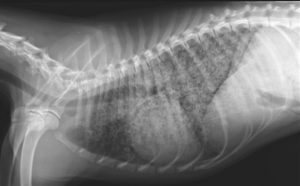

- Radiographs:

- Thorax – hilar lymphadenopathy, miliary to nodular interstitial pattern.

- Radiographs:

-

- Ultrasonography – hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, and mesenteric lymphadenomegaly.

- Finding the organism on cytology or histopathology is the gold standard test

- Cytology

- Numerous small (i.e. 2 to 4µm) round yeast cells inside macrophages.

- In cats, organisms can be found in bone-marrow, lung, lymph nodes and occasionally in peripheral blood smears (monocytes primarily).

- In dogs, rectal scrapings, imprints of colonic biopsy specimens, aspirates of the liver, lung, spleen, and bone morrow are most productive.

- Histopathology

- Pyogranulomatous inflammation (i.e. macrophages and neutrophils) and yeast cells inside macrophages. To learn about the characteristic of the yeast in histology refer to the review article by Hoffmann et al, 2023.

- Cytology

- Antigen and antibody tests:

- Elisa immunoassay antigen (EIA) test (Mira Vista Diagnostics, Indianapolis, ID)

- This is the same antigen test used in dogs and cats to diagnose blastomycosis.

- Because of the cross reactivity between the Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum organisms, this test is also reliable for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in dogs and cats.

- Studies have shown good diagnostic sensitivity (~94%) of the antigen EIA test using urine samples.

- A study in cats showed that urine or serum antigen tests were sensitive to determine disease remission in cats.

- Agar gel immunodifusion test (AGID):

- Currently there is no reliable antibody test.

- The AGID test may be negative in active chronic disease. Moreover, a positive result may indicate previous exposure or resolution of infection.

- This test is not reliable to detect subclinical infection in endemic areas.

- Elisa immunoassay antigen (EIA) test (Mira Vista Diagnostics, Indianapolis, ID)

- Fungal culture – not recommended in a routine practice setting because of the pathogenic potential of this organism. It is generally not needed; however, if culture is deemed necessary, submit the samples to a laboratory with the patient’s detailed history and clinical signs description.

Important Facts

- The patient’s detailed history and clinical signs are important diagnostic tools.

- Thorax radiographs and abdominal ultrasound findings may support a presumptive diagnosis.

- Finding the organisms within macrophages in cytological samples or histopathology is the gold standard test.

- The same urine antigen test (Enzyme Immunoassay – EIA) is sensitive to diagnose histoplasmosis and is currently the recommended test when organisms cannot be found in cytology or histopathology.

- The AGID antibody test is not a very reliable test.

- Fungal culture is not indicated in a practice setting and it is rarely needed. However, it should be performed if other test results are negative. In this case, submit the samples to a laboratory with the patient’s detailed history and clinical signs.

-

Treatment

- Itraconazole: Do not use compounded formulations.

- Dose:

- Dogs and cats: 5 mg/kg q 12-24h.

- Oral suspension (cyclodextrin): 3-5 mg/kg q 12-2 h.

- It can be combined with fluconazole, especially if the eyes and central nervous system are affected.

- Monitor for liver disease.

- Dose:

- Amphotericin B:

- Dose: deoxycholate formulation:

- Dogs: 0.5 mg/kg IV q 48h.

- Cumulative dose: 5-10 mg/kg.

- Cats: 0.25 mg/kg IV q 48h.

- Cumulative dose: 4-8 mg/kg.

- Dogs: 0.5 mg/kg IV q 48h.

- Consider using amphotericin B especially in severe pulmonary disease, central nervous system disease, or gastrointestinal cases with dissemination. Follow with itraconazole therapy.

- Dose: deoxycholate formulation:

- Fluconazole:

- It has better ocular and central nervous system penetration than itraconazole.

- Studies have shown similar effectiveness to itraconazole in dogs. It can be combined with itraconazole in selected cases to improve efficacy.

- It should be considered for central nervous system and ocular cases or cases that do not respond to itraconazole and amphotericin B.

- Dose:

- Dogs: 5 to 10 mg/kg q 12h.

- Cats:

- 50 mg (cats < 4 kg) and 100 mg (cats > 4kg) q 24h.

- 10 mg/kg q 12h.

- Posaconazole or Voriconazole:

- Posaconazole is a newer triazole structurally related to itraconazole.

- Dose:

- Dogs: 5-10 mg/kg q 12-24h.

- Cats: 5 mg/kg q 24h.

- Side effects:

- Inappetence, vomiting, diarrhea and increase in liver enzymes.

- Monitor liver enzymes during treatment.

- Voriconazole is a newer triazole structurally related to fluconazole.

- Dose:

- Dogs: 4-5 mg/kg q 12h. Cats: 2.68 to 5.10 mg/kg q 72-96h or 12.5 mg/cat q 72h. The dose for unusually large or small cats should be based in mg/kg and not mg/cat.

- Side effects:

- At the q 72-96h dose regimen above, the reported side effects are few and less severe and include hyporexia, weight loss, and less commonly ALT increase.

- Cats treated with voriconazole at the dose range of 4.32 mg/kg to 13 mg/kg q 24h are prone to develop various side effects that include one or more of the following: inappetence, mydriasis, apparent blindness, ataxia, nystagmus, tremors, pelvic limb paralysis, cutaneous drug reaction, azotemia, decreased menace and decreased pupillary reflexes.

- Monitor liver enzymes during treatment.

- Terbinafine

- It has shown to have a synergistic effect with azoles.

- Consider using as a salvage drug to increase the effect of azoles.

- Dose: It can be given with or without food

- Dogs: 35-50 mg/kg q 24h.

- Cats: half of 500 mg tablet (i.e 250 mg q 24h).

- Treat for at least 60 days past clinical resolution of signs.

- Generally, most cases are treated with oral antifungals for at least 4 to 6 months.

- Itraconazole: Do not use compounded formulations.

Important Facts

- Itraconazole and fluconazole are similarly effective to treat histoplasmosis.

- Fluconazole should be considered first in cases involving the central nervous sytem or eyes as it penetrate better the blood brain barrier.

- Amphotericin B followed by an azole should be considered in severe cases.

- Terbinafine has shown a synergistic effect with azoles and as such can increase the efficacy of azoles.

- Treat for at least 30 days past clinical resolution of signs.

-

Prognosis

- Pulmonary disease – fair to excellent.

- Disseminated disease – guarded to poor.

- Infected tissues difficult to treat: central nervous system, ocular, bone and epididymis.

- The disease may relapse 6 to 15 months after treatment. In one report, the disease relapsed in a cat 8 years after remission underscoring the need for a long follow-up period.

- To decrease the risk for disease relapse, some clinicians recommend treating for 1 month beyond a negative urine EIA antigen test and then repeat the urine EIA test 1 to 2 months after discontinuing therapy.

References

Aulakh HK, Aulakh KS, Troy GC. Feline histoplasmosis: a retrospective study of 22 cases (1986-2009). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012; 48:3, 182-187.

Barrs VR, Bęczkowski PM, Talbot JT et al. Invasive fungal infections and oomycoses in cats. 1. Diagnostic approach. J Fel Med Surg 2024; doI: 10.1177/1098612X231219696

Barrs VR, Hobi S, Wong A et al. Invasive fungal infections and oomycoses in cats. 2. Antifungal therapy. J Fel Med Surg 2024; doI: 10.1177/1098612X231220047

Easterwood LF, Harkin KR, Rankin AJ. Oral voriconazole therapy in cats with histoplasmosis yielded mild side effects and a favorable outcome. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2023; doi.org/10.2460/javma.23.05.0276.

Greene CE. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier, Saunders, 2012.

Hanzlicek AS, Meinkoth JH, Renschler JS et al. Antigen concentrations as an indicator of clinical remission and disease relapse in cats with histoplasmosis. J vet Intern Med 2016; 30: 1065-1073.

Hoffmann AR, Ramos MG, Walker RT et al. Hyphae, pseudohyphae, yeasts, spherules, spores, and more: A review on the morphology and pathology of fungal and oomycete infections in the skin of domestic animals. Vet Pathol 2023; doi.org/10.1177/03009858231173715

Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier, Mosby, 2013.

Reinhart JM KuKanich KS, Jackson T et al. Feline histoplasmosis: fluconazole therapy and identification of potential sources of Histoplasma species exposure. J Fel Med Surg 2012; 14: 841-848.

Rippon JW. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988.

Scott DW. Large Animal Dermatology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988.

Vishkautsan P, Papich MG, Thompson GR III et al. Pharmacokinetics of voriconazole after intravenous and oral administration to healthy cats. Am J Vet Res 2016; 77: 931–939.

Wilson AG, KuKanich KS, Hanzlicek AS et al. Clinical signs, treatment, and prognostic factors for dogs with histoplasmosis. J AM Vet Med Assoc 2018; 252:201-209.