4.12 Oomycosis – Small and Large Animals

Learning Objectives

- Know that oomycetes that cause disease in animals belong to the genera Pythium, Lagenidium and Paralagenidium. They cause pythiosis, lagenidiosis and paralagenidiosis, respectively.

- Know that oomycetes are not true fungi because they lack ergosterol in their cell membrane. They belong in the kingdom Protista and class Oomycetes.

- Know that oomycetes are ubiquitous in soil and aquatic environments. In the United States, most cases have originated from states bordering the Gulf of Mexico, although there have been reports from Missouri, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Oomycosis has been diagnosed in many countries around the world with subtropical and tropical climate.

- Know that pythiosis appears to be the most common oomycosis of animals and has been reported in dogs, cats, horses and other animal species. Lagenidiosis has been reported in dogs and cats, and paralagenidiosis only in dogs.

- Learn that lagenidiosis and pythiosis are typically progressive and severe diseases that can result in death because they can affect non-cutaneous systems and become disseminated. Few cases of paralagenidiosis have been reported and the disease appears to be limited to the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and have a protracted and slowly progressive behavior.

- Know that animals typically become infected by standing in or drinking stagnant water and damaged skin appears to be a prerequisite for infection.

- Know that ulcerated nodules develop, often rapidly, into large, firm to boggy masses with draining tracts.

- Know that horses with pythiosis develop coral-like bodies in the sinus tracts, which are called leeches, cankers or roots.

- Learn that oomycosis cutaneous lesions are usually very pruritic.

- Know that the diagnosis is based on a characteristic history and clinical signs in addition to the results of one or more of the following tests: cytological exam of aspirate or direct smears of exudate, histopathology, culture, ELISA for serum anti-oomycete, and PCR. The cytological exam will show a granulomatous or pyogranulomatous inflammation with large numbers of eosinophils but rarely organisms can be demonstrated. Histopathology reveals a pyogranulomatous to granulomatous inflammation rich in eosinophils with typically numerous wide, occasionally septate, irregularly branching hyphae. Remember! Oomycetes are similar to Entomopthorales and Mucorales organisms. Oomycete (especially Pythium insidiosum) can be more easily demonstrated in tissue when stained with Grocott or Gomori methenamine silver stain (GMS). Know that oomycetes grow rapidly at 37ºC in blood agar and ideally peptone-yeast-glucose agar. In dogs and cats, small pieces of fresh, nonmacerated tissue are the preferred material for culture. Leeches, vigorously washed in water are the preferred material for culture in horses. For PCR, fresh or frozen ( –70°C ) tissue or DNA extracted directly from culture isolates are the preferred samples.

- Learn the treatment options to manage this condition and the prognosis.

-

General Considerations

- Oomycosis is caused by oomycetes protists in the Stramenopila-Alveolata-Rhizaria supergroup. The causative agents belong to the genera Pythium, Lagenidium and Paralagenidium.

- Oomycetes are taxonomically closer to red algae and Prototheca spp. than to fungi and differ from fungi because they do not generally have ergosterol in their cell membrane and produce motile flagellate zoospores. Their cell wall contains cellulose and beta-glucans.

- The causative agents share some similarities with fungi of the orders Entomopthorales and Mucorales. They all cause a pyogranulomatous inflammation often rich in eosinophils, which is associated with large, sparsely septate hyphae with nonparallel walls.

- Oomycosis, and specially pythiosis, occurs most often in dogs and horses but it has been also reported in cats, sheep, cattle, birds, camels, big cats, bears, fish and humans.

- The skin is often affected but the organisms can invade bone, lungs, and tissues of other organs, especially the gastrointestinal tract.

- Most cases of this disease have been reported in tropical and subtropical areas, mainly Costa Rica, Brazil, Australia, India, Thailand, and southern United States.

- In the United States, most cases have originated from states bordering the Gulf of Mexico, although there have been reports from Missouri, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Kansas, New Jersey and California.

- Oomycosis has been called as: phycomycosis, hyphomycosis, summer sores, swamp cancer, Florida horse leeches, bursatti, and granular dermatitis.

Important Facts

- Oomycosis is caused by oomycetes of the genera Pythium, Lagenidium and Paralagenidium

- Oomycetes are taxonomically closer to red algae and Prototheca spp. than to fungi and differ from fungi because they do not generally have ergosterol in their cell membrane and produce motile flagellate zoospores.

- The causative agents of oomycosis share similarities with fungi of the orders Entomopthorales and Mucorales

- Most cases have been reported in tropical and subtropical areas.

- In the United States, most cases have originated from states bordering the Gulf of Mexico.

-

Cause and Pathogenesis

- Oomycosis is caused by water molds, which include Pythium insidiosum (dog, cat, horse and other species), Lagenidium giganteum forma caninum (dog), Lagenidium deciduum (cat), and Paralagenidium karlingii (dog).

- They belong in the kingdom Stramenopila and class Oomycetes and are found throughout the world.

- Pythium insidiosum causes pythiosis, Lagenidium spp. causes lagenidiosis, and Paralagenidium spp. causes paralagenidiosis. Pythiosis appears to be the most common disease.

- The organisms are associated with soil and standing bodies of fresh water. Many animals become infected by standing in or drinking stagnant water and damaged skin appears to be a prerequisite for infection. Infected animals are not typically immunocompromised.

- The motile biflagellate zoospore stage shows chemotaxis towards decaying plants and animal tissues. They then attach to the host tissue, encyst, develop a germ tube, and actively infect the host.

- Most cases are seen during the summer and fall in tropical and subtropical areas of the world.

Important Facts

- The causative agents of oomycosis are water molds in the class Oomycetes including Pythium insidiosum (dog, cat, horse and other species), Lagenidium giganteum forma caninum (dog), Lagenidium deciduum (cat), and Paralagenidium karlingii (dog).

- The organisms are associated with soil and standing bodies of fresh water.

- Animals become infected by standing in or drinking stagnant water and damaged skin appears to be a prerequisite for infection.

- Most cases are seen during the summer and fall in tropical and subtropical areas of the world.

-

Clinical Signs

- Dogs:

- Dogs have been diagnosis with pythiosis, lagenidiosis and paralagenidiosis.

- Large-size, young adult, male dogs and outdoor working breeds are most commonly affected probably because they are more exposed to the areas where oomycetes live.

- German shepherd dogs and Labrador retrievers appear to be particularly susceptible to pythiosis.

- Pythiosis is a severe disease that is often fatal. Pythium insidiosum can cause progressive gastrointestinal or cutaneous disease. The disease can rarely affect the respiratory tract or become disseminated. The gastrointestinal form predominates in dogs and is characterized by diarrhea, fever, anorexia, lethargy, and weight loss. Invasion of mesenteric vessels may result in bowel ischemia, infarction, perforation, and acute hemoabdomen. The infection can rarely invade adjacent tissues such as the uterus or pancreas.

- Lagenidiosis is also a progressive and severe disease. The organism can invade great vessels in the abdomen, which may result in their rupture and ultimately hemoabdomen. Regional lymph nodes, lungs, pulmonary hilus or cranium mediastinum can be affected. Masseter muscle infection that progressed to invade the brain has been reported in a dog. Occult systemic lesions involving the chest and abdominal organs are common in infection caused by Lagenidium giganteum forma caninum.

- Paralagenidiosis appears to be a more protracted and slowly progressive disease. Lesions are generally limited to the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues.

- In pythiosis, lagenidiosis and paralagenidiosis, cutaneous lesions involve the dermis and often extend to the subcutaneous tissue. They are characterized by nonhealing ulcerated nodules that develop, often rapidly, into large, firm to boggy masses with draining tracts. The disease can extend to regional lymph nodes. Non-ulcerated nodules may also be present.

- Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions can be solitary or multiple and are usually confined to one area of the body, especially the legs, face, and tail head. Cutaneous lesions tend to be progressive, locally invasive, and poorly responsive to therapy.

- Lesions are often pruritic.

- Early lesions on distal limbs may resemble acral lick dermatitis.

- Rarely, dogs develop locally invasive (skeletal) or disseminated infection, which can occur with lagenidiosis or chronic pythosis.

- Cats:

- Oomycosis is rarer in cats than dogs. Cases reported in cats were caused by Pythium insidiosum. However, an anecdotal report of a cat with lagenidiosis caused by Lagenidium deciduum can be found in review articles. This cat had chronic and pruritic skin lesions along the caudal dorsum characterized by miliary dermatitis that evolved to form erythematous to whitish plaques.

- Cats under 12 months of age appear to be predisposed but the disease can occur at any age. There is no breed or sex predilection.

- The disease is typically protracted in cats and often limited to the subcutaneous tissue; however, dermal nodules that may ulcerate and drain can also develop.

- Gastrointestinal pythiosis can occur in cats. The small intestine is typically affected and mesenteric lymph nodes can be involved. Clinical signs include one or more of the following: anorexia, vomiting, hematemesis, weight loss and diarrhea.

- Horses:

- Currently, only pythiosis has been reported in horses.

- Subcutaneous lesions are typically found in the distal extremities, neck, perianal areas, ventral abdomen and chest.

- Lesions are usually single and unilateral but may be multiple and bilateral.

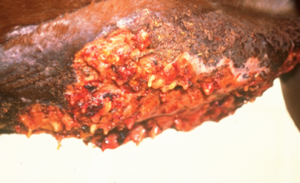

- Large (up to 45 cm) roughly circular, ulcerative granulomas with a serosanguineous discharge are characteristic.

- Dogs:

-

-

- Numerous elongated, gritty, gray-white to yellowish, coral-like bodies are present in the sinus tracts. These bodies are composed of Pythium filamentous structures and reactive host tissue.

-

-

-

- Because of their gross appearance, these bodies were originally described as cankers, leeches, or roots.

- Lesions are usually very pruritic.

- Limb edema, tendon sheath involvement, joint involvement, lameness, and regional lymphadenopathy may occur in chronic cases. Lesions older than 2 months can be associated with osteomyelitis. Bone involvement is not typically seen in lesions less than 4 weeks old.

-

-

-

- Systemic involvement is rare, with lesions of lymph nodes, trachea, lungs and, stomach being described.

-

Important Facts

- Dogs have been diagnosis with pythiosis, lagenidiosis and paralagenidiosis, cats with pythiosis and lagenidiosis and horses only with pythiosis.

- Pythiosis and lagenidiosis are considered severe diseases in dogs and paralagenidiosis is a more protracted and slowly progressive disease limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissues.

- In dogs and horses, ulcerated dermal to subcutaneous nodules develop, often rapidly, into large, firm to boggy masses with draining tracts.

- Lesions are often pruritic.

- German shepherd dogs and Labrador retrievers appear to be more susceptible to have pythiosis.

- Horses develop coral-like bodies in the sinus tracts, called cankers, leeches or roots.

- Systemic involvement is rare.

-

Diagnosis

- Cytology: Cytological examination of aspirates from lymph nodes, thickened gastrointestinal wall, or cutaneous nodules/plaques and direct smears from exudates reveal granulomatous to pyogranulomatous inflammation often associated with numerous eosinophils. However, organisms are rarely seen and if present, they will not stain or will appear basophilic.

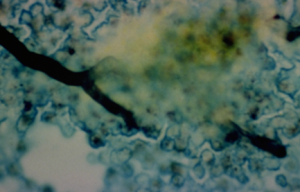

- Incisional biopsy: Histopathology is characterized by a nodular to diffuse granulomatous to pyogranulomatous inflammation and panniculitis. Large numbers of eosinophils are typically present. Multiple foci of necrosis associated with neutrophils, eosinophils, and macrophages can be present. Moreover, discrete granulomas composed of multinucleate giant cells, epithelioid macrophages, and fewer neutrophils and eosinophils are often present. Oomycetes are typically found within areas of necrosis or at the center of granulomas but occasionally they can be seen invading blood vessel walls (especially arterial). As a result, thrombosed vessels may be a prominent feature. Oomycetes are characterized by wide, thick-walled, occasionally septate, non-parallel, and irregularly branching hyphae. The hyphae are similar to those of Entomophthoromycetes and Mucoromycetes organisms. Pythium insidiosum will not stain or will appear basophilic with H&E stain. This helps differentiate this oomycete from Lagenidium spp., Paralagenidium spp., Entomophthoromycetes, and Mucoromycetes organisms, which generally stain with H&E. In contrast to Entomophthoromycetes and Mucoromycetes organisms, oomycetes stain poorly with periodic-acid-Schiff (PAS) but nicely with Grocott or Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain.

-

- Culture: It is the gold standard test but its sensitivity is low, therefore, false negative results are common. Oomycetes generally grow within 12 to 48h at 37◦C in blood agar or ideally peptone-yeast-glucose agar. In dogs and cats, small pieces of fresh, nonmacerated tissue are the preferred material for culture. Leeches vigorously washed in water or incisional biopsies are the preferred samples for culture in horse cases. Leeches are not present in other animal species. The collected samples have to be transported in water at room temperature within 24h of collection. Submit samples in cold packs if it will take more than two days to arrive at the laboratory. It is recommended to submit samples to veterinary diagnostic laboratories with expertise in identifying oomycetes (e.g. Clinical Bacteriology and Mycology Laboratory, University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine https://vetmed.tennessee.edu/vmc/dls/bacteriology/; University of Florida Veterinary Diagnostic Labs, Molecular Fungal ID Lab: https://cdpm.vetmed.ufl.edu/services/diagnostic-labs/molecular-fungal-id-laboratory/; Department of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University: https://www.vetmed.auburn.edu/academic-departments/dept-of-pathobiology/).

- Serologic Testing: An ELISA test for detection of anti-Pythium insidiosum serum antibodies has been reported to be sensitive and specific. However, a serum anti-Pythium insidiosum ELISA offered by the Auburn University has shown to have poor specificity. Sensitive and specific ELISA or immunochromatographic assays that use the bacterial protein A/G as a conjugate have been reported. ELISA tests can also be used to monitor response to therapy. Currently, there is no sensitive and specific ELISA test for the identification of Lagenidium spp. and Paralagenidium spp serum antibodies.

- Molecular Tests: A tissue species-specific PCR has been used to identify Pythium insidiosum and has shown to be sensitive and specific. Therefore, it is important that the amplicons are properly sequenced to confirm their identity as Pythium insidiosum. Amplification and sequencing of ribosomal DNA is currently the only diagnostic test that differentiates Lagenidium giganteum f. caninum, Paralagenidium karlingii, clade AG-2015a Paralagenidium isolates and Lagenidium deciduum. Fresh or frozen (-70°C) tissue or DNA extracted directly from culture isolates are the preferred samples. Moreover, amplification and sequencing of DNA from paraffin-embedded tissues using panfungal primers have become available. Sensitivities of these panfungal tests have ranged from 54% to 94%.

- Differential diagnoses include infectious granulomas, foreign-body granulomas, acral lick dermatitis (dogs), habronemiasis (horses), exuberant granulation tissue (horses), and neoplasia.

Important Facts

- The diagnosis of oomycosis is based on a characteristic history and clinical signs and one or more of the following tests: cytology, histopathology, oomycete culture, ELISA antibody test, and PCR test.

- Cytological examination of aspirates from lymph nodes and nodules and direct smear from exudates rarely demonstrate the organisms.

- Histopathology reveals a granulomatous to pyogranulomatous inflammation often rich in eosinophils and often associated with numerous wide, occasionally septate, irregularly branching hyphae.

- Pythium insidiosum usually requires Gomori or Grocott methenamine silver stain to be visualized in biopsy tissues.

- The hyphae of Entomophthoromycetes and Mucoromycetes organisms are similar to those of oomycetes.

- Oomycetes grow rapidly at 37ºC in blood agar or ideally peptone-yeast-glucose agar.

- Small pieces of fresh, nonmacerated tissue are the preferred material for culture. However, leeches vigorously washed in water are the preferred samples in horse cases. Leeches are not present in other animal species.

- Currently, there is no sensitive and specific ELISA test for the identification of Lagenidium spp. and Paralagenidium spp. serum antibodies.

- Species-specific PCR tests have been used to identify oomycete organisms. Fresh or frozen (-70°C) tissue and DNA extracted directly from culture isolates are the preferred samples.

-

Treatment and Prognosis

- Treat early to improve prognosis!

- If possible, wide surgical excision (ideally, 5cm margins) is the treatment of choice but recurrence is about 30%. Amputation of the affected limb may be indicated in dogs and cats. Because lesions have the potential to expand rapidly, surgical removal is recommended before confirming the diagnosis in typical cases. Success of surgical treatment correlates with size, location and duration of lesions. Lesions on the leg are difficult to remove completely. Intervene as soon as new foci of infection develop. They typically appear as black to red hemorrhagic spots in the new granulation bed. A typical case is treated with one major surgical intervention and two to three “retrims”. In infections caused by Lagenidium giganteum f. caninum occult systemic lesions are common; therefore, radiographic imaging of the chest and abdomen and ultrasound imaging of the abdomen are recommended to determine the extent of disease prior to attempting surgical resection of cutaneous lesions.

- Serum anti-Pythium insidiosum ELISA test can be performed at the time of surgery and 2 to 3 months later.

- Because Pythium insidiosum organism does not share cell wall components with true fungi (i.e. lack ergosterol and chitin), antifungal agents have been generally disappointing in the treatment of this disease. However, because local postoperative disease recurrence is common, combination of itraconazole (10 mg/kg, orally, q 24h) and terbinafine (5-10 mg/kg, orally, q 24h) is often recommended after surgery for 2-6 months.

- It has been noted that Pythium insidiosum lesions may shrink 10 to 25% during treatment with itraconazole but grow rapidly once therapy is withdrawn. However, medical therapy may be useful in shrinking some lesions to a size that is then surgically resectable.

- Mefenoxam has been used in combination with itraconazole and terbinafine in dogs with nonresectable or incompletely resected pythiosis. Anecdotal reports indicate that mefenoxam is not effective as sole therapy to treat pythiosis in dogs. In addition, pharmacokinetic and safety studies have not been done in dogs, thus, this drug is not currently recommended to treat pythiosis.

- Immunotherapy using a vaccine developed with antigen from Pythium insidiosum has been used with success in horses with early lesions (less than 2 weeks).

- In one study, 53% of horses with cutaneous pythiosis were cured with immunotherapy alone.

- Immunotherapy does not work well in chronic cases (lesions older than 2 months).

- The response to immunotherapy in dogs has been generally poor.

- One sheep recovered after being treated with potassium iodide at the dose of 7 mg/kg daily for 7 days.

- An in vitro and in vivo (rabbits) study showed that photodynamic therapy using chlorine was effective in inhibiting the growth of Pythium insidiosum. Experimentally infected rabbits showed signs of improvement 3 days after treatment. However, more studies need to be done before this treatment modality can be part of the treatment regimen of oomycosis.

- Currently, the best treatment modality may be a combination of surgery, antifungal drugs (azoles combined with terbinafine) and immunotherapy (horses with early lesions).

- Prognosis: Surgery can be curative in many animals with a distal limb lesion where the leg is amputated or with a midjejunal lesion assessed as completely excised with 5cm margins. Prognosis is worse for leg lesions of more than 2 months duration because bone involvement will likely be present. Prognosis is also poor in dogs with gastrointestinal involvement, disseminated disease, and lagenidiosis. Severe cases are often euthanized.

Important Facts

- Wide surgical excision (if feasible) is the treatment of choice but recurrence is common.

- In infections caused by Lagenidium giganteum f. caninum occult systemic lesions are common; therefore, radiographic imaging of the chest and abdomen and ultrasound imaging of the abdomen are recommended to determine the extent of disease prior to attempting surgical resection of cutaneous lesions.

- Because oomycetes do not share cell wall characteristics with true fungi, efficacy of antifungal chemotherapy has been generally disappointing in the treatment of this disease. However, the combination of itraconazole and terbinafine resulted in cure in a human patient and has been used in animals to decrease the risk of recurrence post-surgery and to reduce the size of lesions before surgery.

- Immunotherapy using a vaccine developed with antigen from Pythium insidiosum has been used with success in horses with early lesions. However, this treatment modality has not worked well in dogs.

- Immunotherapy does not work well in chronic cases.

- Mefenoxam is not currently recommended to treat oomycosis because of lack of evidence of efficacy as sole therapy and no pharmacokinetic and safety studies in animals.

- Currently, the best treatment modality may be a combination of aggressive surgery, antifungal chemotherapy (i.e. an azole plus terbinafine) and immunotherapy (horses with early lesions).

References

Barrs VR, Bęczkowski PM, Talbot JT et al. Invasive fungal infections and oomycoses in cats. 1. Diagnostic approach. J Fel Med Surg 2024; doI: 10.1177/1098612X231219696

Dedeaux A, Grooters A, Wakamatsu-Utsuki N, et al. Opportunistic fungal infections in small animals. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018;54: 327–37.

Dehghanpir SD. Cytomorphology of deep mycoses in dogs and cats. Vet Clin Small Anim 2023; 53: 155–173.

Do Carmo PMS Uzal FA, Riet-Correa F. Diseases caused by Pythium insidiosum in sheep and goats: a review. J Vet Diag Invest 2020; https://doi.org/10.1177/104063872096893

Greene CE. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier, Saunders, 2012.

Grooters AM. Miscellaneous fungal diseases. In: Sykes JE, editor. Greene’s infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 5 edition. Elsevier; 2022.

Grooters AM. Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, paralagenidiosis, entomophthoromycosis, and mucormycosis. In: Sykes JE, editor. Greene’s infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 5 edition. Elsevier; 2022.

Hensel P, Greene GE, Medleau L et al. Immunotherapy for treatment of multicentric cutaneous pythiosis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 223: 215-218.

Hoffmann AR, Ramos MG, Walker RT et al. Hyphae, pseudohyphae, yeasts, spherules, spores, and more: A review on the morphology and pathology of fungal and oomycete infections in the skin of domestic animals. Vet Pathol 2023; doi.org/10.1177/03009858231173715

Jaturapaktrarak C, Payattikul P, Lohnoo T, et al. Protein A/G-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of anti-Pythium insidiosum antibodies in human and animal subjects. BMC Res Notes 2020;1 3:135. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-04981-y

Mendoza L and Vilela R. The mammalian pathogenic oomycetes. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2013; 7:198-208.

Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier, Mosby, 2013.

Pires L, Bosco S MG, da Silva Junior NF et al. Photodynamic therapy for pythiosis. Vet Dermatol 2013;.24:130-136.

Rippon JW. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988.

Scott DW. Large Animal Dermatology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988.

Tabosa IM, Riet-Correa F, Nobre VMT et al. Outbreaks of pythiosis in two flocks of sheep in Northeastern Brazil. Vet Pathol, 2004; 41:412-415,.

Thomas RC, Lewis, DT. Pythiosis in dogs and cats. Compend Cont Educ 1998; 20: 63 – 75,.