3.22 Pelodera Dermatitis – Small Animals

Learning Objectives

- Know the cause of pelodera dermatitis.

- Learn the predisposing factors associated with peolodera dermatitis.

- Know to diagnose pelodera dermatitis.

- Learn how to manage pelodera dermatitis.

-

General Considerations

- Pelodera or rhabditic dermatitis is an erythematous, nonseasonal pruritic dermatitis caused by the cutaneous infestation with the third-stage larva of Pelodera strongyloides.

- Pelodera strongyloides is a free-living nematode that completes its entire life cycle in organic matter.

- The adult parasite lives in damp soil or moist, decaying organic matter such as straw, leaves, hay, and rice hulls.

- Larvae may invade skin, which contacts the contaminated soil or organic material and initiates cutaneous inflammation.

- Various mammalian species can be affected including humans.

-

Cause

- Third stage larva of the free-living nematode Pelodera strongyloides.

-

Clinical Signs

- Lesions associated with this infestation are typically present in areas of the skin that contact the ground, such as feet, legs, perineum, ventral chest, abdomen and tail.

- Focal or diffuse alopecia, erythema, papules and nodules are initially present.

-

- Later, crusts, scales and secondary bacterial infection may occur.

- The skin may become lichenified and hyperpigmented in chronic cases.

- Pruritus can vary from mild to intense.

- Differential diagnoses include sarcoptic mange, atopic dermatitis, primary contact dermatitis, demodectic mange, hookworm dermatitis, and dirofilariasis.

-

Diagnosis

- History and clinical signs.

- Deep skin scrapings will demonstrate the small motile nematode larvae (625 to 650 µm in length and 25-40 µm in diameter) in most cases.

- Trichoscopy may show the larva. Pluck various hairs from affected areas, place a few drops of mineral oil, cover with a coverslip, and look under the microscope.

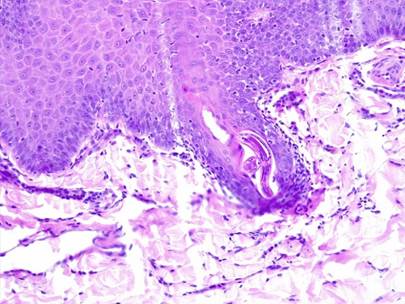

- Skin biopsy can also reveal nematode segments within hair follicles and within pyogranulomatous reactions in the dermis when hair follicles rupture.

-

- If deep skin scrapings are negative, perform trichoscopy. If trichoscopy and skin scrapings are negative, perform a skin biopsy.

-

Treatment

- Treatment is effective and simple.

- Change the animal’s environment, which is harboring the larvae.

- After cleaning the environment, spray all ground surfaces with malathion (one ounce of 57-59% malathion per gallon of water).

- New bedding consisting of wood chips, old blankets, or shredded paper can be utilized.

- Animals should be bathed with a medicated shampoo to remove the scales and crusts.

- The infestation is self-limiting and resolves spontaneously after the animals are removed from the source of contamination. However, two applications of moxidectin + imidacloprid (Advantage Multi®) has been shown to be effective. Other ectoparasiticides may also be efficacious but it is questionable if their use is needed.

- Appropriate antibiotic therapy should be used if secondary pyoderma is present (ideally topical treatment if feasible).

- Prednisone can be given for a few days if pruritus is intense.

Important Facts

- Pelodera dermatitis is caused by the skin penetration of larvae of the free-living nematode Pelodera strongyloides.

- The adult nematode lives in damp soil or moist decaying organic matter such as straw, hay and leaves.

- Lesions consist of alopecia, erythema, papules and crusts and are located to the body sites that contact the ground.

- Pruritus can be mild to severe.

- Diagnosis can be confirmed based on deep skin scrapings, trichoscopy, or skin biopsy.

- Treatment consists of cleaning the animal’s environment and using a parasiticide such as, malathion.

- Once the environment is cleaned, the lesions should be self-limiting.

- Ectoparasiticides may be needed in some cases and two applications of moxidectin+imidaclorid has been effective

- Pelodera dermatitis has also been reported in cattle, horses, and sheep.

- The clinical signs, diagnosis and treatment are the same as described for dogs.

References

Capitan RGM and Noli C. Trichoscopic diagnosis of cutaneous Pelodera strongyloides infestation in a dog. Vet Dermatol 2017; 28: 413-e100.

Di Bari MA, Di Pirro V, Ciucci P et al. Pelodera strongyloides in the critically endangered Apennine brown bear (Ursus arctos marsicanus). Res Vet Sci 2022; 145: 50–53.

Rasmir-Raven AM, Black SS, Richard LG et al. Papillomatous pastern dermatitis with spirochetes and Pelodera strongyloides in a Tennessee Walking horse. J Vet Diagn Invest 2000; 12: 287-91.

Saari SAM and Nikander SE. Pelodera (syn. Rhabditis) strongyloides as a cause of dermatitis – a report of 11 dogs in Filand. Acta Vet Scandin 2006; 48:18.

Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE: Parasitic Skin Diseases. Small Animal Dermatology. 5th edn. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1995; 395-398.

Scott DW. Parasitic Diseases. Large Animal Dermatology. 1st edn. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1988; 265-266.

WB Willers. Pelodera strongyloides in association with canine dermatitis in Wisconsin. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1970; 156: 319-320.