4.3 Malassezia Dermatitis – Small Animals

Learning Objectives

- Know that Malassezia spp. are part of the skin and ear microbiota of dogs and cats.

- Remember to always look for an underlying condition when dealing with a case of Malassezia overgrowth/dermatitis.

- Learn the common predisposing diseases associated with Malassezia overgrowth/dermatitis.

- Know how to recognize clinically a case of Malassezia dermatitis.

- Remember that cytological examination is the most reliable diagnostic tool. Learn the diagnostic methods.

- Know how to manage a case of Malassezia dermatitis.

-

General Considerations

- Malassezia organisms are part of the skin microbiota of dogs and cats. However, they are known to produce various virulent factors. When Malassezia organisms overgrow on the skin surface, the accumulated virulent factors may induce dermatitis.

- Many primary diseases can predispose the animals to Malassezia overgrowth likely due to changes in the skin barrier and microenvironment. The following are some examples of predisposing factors:

- Atopic dermatitis.

- Food allergy.

- Irritant or allergic contact dermatitis.

- Endocrinopathies.

- Keratinization disorders.

- Ectoparasitism.

- Generalized Malassezia dermatitis in cats should alert the clinician to the presence of a systemic disease (e.g. cancer, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, etc.).

- Sphynx and Devon Rex cats carry larger numbers of Malassezia organisms on their skin and are predisposed to Malassezia dermatitis/overgrowth.

- The role of Malassezia organisms as a primary pathogen of the skin and ears is unclear.

-

Etiology

- Malassezia pachydermatis is the most common agent of Malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats. However, various other Malassezia species can also overgrow on the skin of cats and dogs and cause dermatitis.

- All species are lipophilic and lipid-dependent. However, in contrast to other Malassezia species, Malassezia pachydermatis can grow in Sabouraud’s dextrose agar because it is capable to utilize fractions of lipid within the peptone component of the agar.

- Malassezia organisms are commonly found in normal and abnormal skin, in normal and abnormal ear canals, and in the anal sacs, rectum, and vagina of normal dogs and cats.

-

Clinical Signs

- Clinical signs are quite variable:

- Pruritus is variable but it is usually severe. Remember that Malassezia dermatitis often aggravates the pruritus level associated with environment- or food-induced atopic dermatitis.

- Greasy seborrheic dermatitis (e.g. oily skin/coat, erythema with or without adhered yellowish scales) is more often seen in terriers (e.g. Yorkshire terrier), shih tzu, Lhasa apso, and hounds.

- Clinical signs are quite variable:

-

-

- Interdigital erythema and/or seborrhea oleosa are a common clinical presentation, especially in dogs with atopic dermatitis. It can be seen in many dog breeds, especially cocker spaniels and bulldogs. These dogs are often very pruritic. A brownish/rusty discoloration of the hair and skin can be seen and when present, be suspicious of Malassezia dermatitis/overgrowth. Dogs with chronic Malassezia pododermatitis may have a black discoloration of the nail plate indicating the overgrowth of Malassezia organisms.

-

-

-

- Mucocutaneous junctions (e.g. lip folds) can be affected and typically shows erythema and brownish discoloration of hairs and sometimes skin surface.

-

-

-

- Intertriginous areas such as, axilla, groin and perivulvar region, typically present with erythema with or without brownish discoloration of hairs and skin surface. Scales may also be present.

-

-

-

- In chronic cases, the skin becomes lichenified and hyperpigmented. Look for Malassezia overgrowth in lichenified skin!

-

-

Diagnosis

- Cytology is the most useful and readily available diagnostic tool.

- Skin surface samples are collected as described below. Notice that the method varies depending on the affected site and lesion characteristic (i.e. dry or oily).

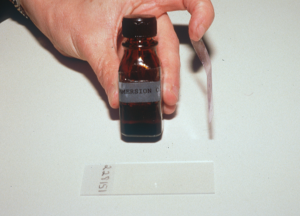

- Press a piece of transparent cellophane tape onto the lesional skin at least three times. This is the most used and most effective test. It is the ideal method if the skin surface is dry.

- Skin surface samples are collected as described below. Notice that the method varies depending on the affected site and lesion characteristic (i.e. dry or oily).

- Cytology is the most useful and readily available diagnostic tool.

-

-

-

- Dry superficial scraping (do not place oil on the scalpel blade) – this method is only useful if the affected skin is oily.

-

-

-

-

-

- Rub vigorously a cotton swab on the skin surface – this method is only useful if the affected skin is oily and has abundant surface material.

-

-

-

-

-

- Press a clean glass slide on the skin surface (i.e. direct imprint) – this method is only useful if the affected area is flat and oily.

-

-

-

-

- Staining methods:

- If using a swab or direct imprint, the material transferred to a glass slide is heat fixed and stained with all three Diff Quick stains or another Romanowsky stain. Thereafter, gently rinse and thoroughly dry the stained slide, cover the sample with immersion oil and microscopically examine it using the oil objective (i.e. 100x).

- Staining methods:

-

-

-

-

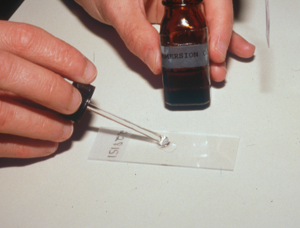

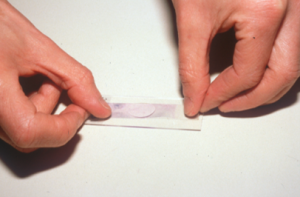

- If using a cellophane tape, do not use the first Diff Quick stain (light blue, fixative reagent) because it contains alcohol, which will damage the tape. Use the eosinophilic (Xanthene dye) and the basophilic (Thiazine dye) stains or solely the basophilic dye to stain (authors’ preference). Make sure to gently rinse the tape (both sides) to remove the excess stain and dry it thoroughly before adding the immersion oil.

-

-

-

-

-

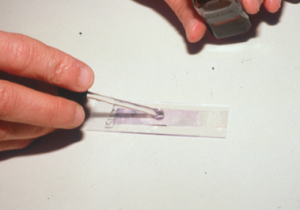

- The next step is to put first a drop of immersion oil on the glass slide then the stick part of the tape over the oil, and again another drop of immersion oil on the tape surface. You can also place the stick part of the tape directly on the glass slide and place the immersion oil solely on the top surface of the tape.

-

-

-

-

-

- Examine your samples under the immersion oil objective (100x).

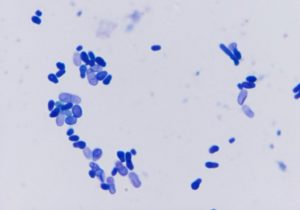

- Findings: budding yeast often associated with squamous cells (i.e. corneocytes).

-

-

-

- Culture –It is rarely needed to diagnose Malassezia dermatitis/overgrowth. Modified Dixon’s agar is the ideal medium to isolate Malassezia spp organisms. However, if this medium is unavailable, Sabouraud’s dextrose agar supplemented with 1% Tween 80 can be used. Some Malassezia pachydermatis strains may grow in Sabouraud’s dextrose agar without supplementation.

- Skin biopsy is only performed in cases where the clinical signs are unusual.

- Skin biopsy is less reliable to demonstrate Malassezia organisms than cytological examination because tissue processing can eliminate parts of the stratum corneum where the yeast organisms live.

- Yeast organisms may be also present in the infundibulum of hair follicles.

- Do not scrub or use alcohol on the skin surface before biopsying because Malassezia organisms may be mechanically removed.

-

Treatment: Remember! Identifying and treating an underlying disease is crucial to effectively manage Malassezia dermatitis and prevent recurrences.

- Topical shampoos:

- Degreasing shampoos – to be effective make a good lather and massage the shampoo into the skin for 5-10 minutes before rinsing it thoroughly. Products containing the following ingredients will remove the excess oil from the skin efficiently.

- 1.0% selenium sulfide in Selsun Blue® shampoo. Light color coats may acquire a temporary brownish/yellowish discoloration.

- Benzoyl peroxide.

- Coal tar.

- Dish soaps: Dawn – excellent to remove the excess oil/sebum; make a good lather, rinse it off thoroughly and follow with the medicated shampoo.

- Shampoos containing one or more of the following antifungal ingredients:

- Miconazole nitrate 2%, chlorhexidine 3% or 4% (2% if combined with another antifungal such as 2% miconazole) and ketoconazole.

- These shampoos are not degreasing.

- Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Degreasing shampoos – to be effective make a good lather and massage the shampoo into the skin for 5-10 minutes before rinsing it thoroughly. Products containing the following ingredients will remove the excess oil from the skin efficiently.

- Other topicals:

- When only the feet or a focal area is affected, you can use topical creams, ointments or lotions containing antifungal agents (such as clotrimazole, miconazole, nystatin, terbinafine, acetic acid, boric acid).

- Topical products containing a glucocorticoid and an antifungal (examples: clotrimazole + betamethasone or mometasone) are very efficacious to reduce inflammation; however, they should be used carefully to avoid undesirable side effects. Most of these commercial products will also have an antibiotic (e.g. gentamicin).

- Rinses, sprays, mousses, pads and wipes containing miconazole, chlorhexidine, or ketoconazole should be used in between baths to provide residual effect and prevent recurrences in animals predisposed to Malassezia dermatitis/overgrowth.

- When combined with shampoos these topicals can be used as sole therapy but in some cases systemic therapy will be needed.

- Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Systemic therapy – Can be considered in generalized cases and cases that do not respond solely to topical therapy. Combine with topical therapy to reduce the disease course.

- Ketoconazole 5 to 10 mg/kg q 24h for at least 30 days. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy. Give it with food to improve absorption.

- Itraconazole 5 mg/kg q 24h for at least 30 days. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Fluconazole 5 to 10 mg/kg q 24h for at least 30 days. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Terbinafine 40 mg/kg q 24h for at least 30 days. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Pulse therapy:

- Itraconazole (dog): 5 mg/kg q 24h for 2 consecutive days per week for 4 weeks or longer. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Itraconazole (cat): 5 mg/kg q 24h for 7 days alternating with 7 days without treatment for 4 weeks or longer. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Terbinafine (dog): 30-40 mg/kg q 24h for 2 consecutive days per week for 4 weeks or longer. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Advantages of pulse therapy include (i) less exposure to the drug; (ii) less risk for side effects; (iii) increase client compliance; (iv) reduce cost.

- Concern with pulse therapy is the risk for resistance development.

- Topical shampoos:

Important Facts

- Malassezia organisms are part of the skin and ear microbiota of dogs and cats.

- Always look for an underlying condition when dealing with Malassezia dermatitis!

- Common predisposing causes are allergies, endocrinopathies and keratinization disorders.

- An underlying disease may not be identified in some cases.

- Some dog and cat breeds are predisposed to Malassezia overgrowth/dermatitis.

- The affected skin can be dry or oily.

- Paws are a commonly affected site in dogs and they usually present with severe pruritus.

- Cytological examination is the most useful diagnostic tool.

- A dry scraping of oily areas and the cellophane tape preparation appear to be the most reliable methods to collect samples for cytology.

- Topical therapy with degreasing and/or antifungal shampoos is usually effective.

- Systemic therapy in combination with topical therapy may be required in generalized cases and cases that do not respond solely to topical therapy.

- Recheck the patient before discontinuing treatment.

References

Bajwa JJ. Canine Malassezia dermatitis. Can Vet J 2017; 58: 1119–1121.

Bond R, Morris D, Guillot J et al. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats. Vet Dermatol 2020; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12809.

Bond R, Morris D, Guillot J et al. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats. Clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol 2020; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12834.

Lee H, Koo Y, Yun T et al. A single-blind randomised study comparing the efficacy of fluconazole and itraconazole for the treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in client-owned

dogs. Vet Dermatol 2024; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13233.

Scott, Miller, Griffin. Small Animal Dermatology. In: Fungal Skin Diseases. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1995, p 351– 357.