1.5 Dermatophilosis

Learning Objectives

- Describe the etiologic agent of dermatophilosis.

- Can dermatophilosis be transmitted to humans?

- What are the two most important predisposing factors necessary for initiation and development of dermatophilosis?

- Describe the clinical signs in horses, cattle, sheep, goats and llamas.

- How do you manage dermatophilosis?

-

General Considerations

- Common infectious dermatitis of horses, cattle, sheep, goats and llamas.

- Worldwide distribution.

- The disease is rarely transmitted to man by contact with infected animals.

-

Etiology and Pathogenesis

- The disease is caused by Dermatophilus congolensis a gram positive, aerobic or facultative anaerobic actinomycete bacteria (i.e. filamentous or fungus-like bacteria).

- Subclinical carriers and crusts from affected animals are the primary sources of infection. Dermatophilus congolensis has not been isolated from soil. Therefore, it is believed that the organism lives in quiescent form in chronic but subclinical infections until favorable conditions release its infective form.

- Examples of mechanical modes of transmission include biting and non-biting flies and contaminated clippers.

- Rain or any other source of moisture results in the release of motile, flagellated zoospores, which is the infective stage of the organism. Moisture can macerate the stratum corneum facilitating skin damage.

- Infection does not occur until skin damaged occurs. Some sources of skin damage include flies and arthropode bites, and prickly vegetation. Skin maceration caused by moisture facilitates damage.

- Prolonged wetting of the skin by rain or other moistening sources and skin damage are the two most important predisposing factors. Concurrent disease(s) can also predispose to dermatophilosis.

- Some individuals appear to have natural resistance to the disease.

- Second infections tend to be less severe and resolve quicker than first infections.

- Tick infestation and immune suppression result in a more severe form of the disease.

-

Clinical Signs

- Equine:

- The disease is usually seen during wet, rainy seasons since moisture is an important predisposing factor. Other predisposing factors are skin damage and concurrent disease(s).

- The dorsal surfaces of the body are primarily affected.

- Acute lesions are painful, not pruritic.

- Thick crusts can be palpated under the hair coat.

- Equine:

-

-

- When these crusts are manually removed, the adhered hair shafts come with the crusts, exposing a pink, moist skin surface.

-

-

-

- The undersurface of the crusts is usually concave with the roots of hair shafts protruding.

- The crusts here described are not pathognomonic for dermatophilosis and may be seen with dermatophytosis, staphylococcal folliculitis or pemphigus foliaceus. These diseases should be considered as differential diagnoses for dermatophilosis.

- When horses graze in wet pasture, lesions may be confined to the muzzle and lower legs.

- Chronic lesions are characterized by patchy to coalescing alopecia and scaling.

-

-

-

- White-skinned and white-haired areas are more sensitive to infection. Photodermatitis may be associated with dermatophilosis in these depigmented areas, which will aggravate the disease.

-

-

- Bovine:

- Predisposing conditions include trauma, moisture, concurrent disease, and poor nutrition.

- Crusts will develop on the face and ears (milk scald in calves), rump and topline, brisket, axillae, groin, udder, teats, prepuce, scrotum, distal limbs, perineum, and tail.

- Bovine:

-

-

- Cutaneous horns can develop in chronic lesions.

- Animals with over 50% of their body affected will show rapid weight loss.

- Significant economic loss to hide.

-

-

- Sheep:

- Most common lesions include:

- Crusts on the ears, muzzle and face of lambs.

- Crusts on the topline over the back (known as lumpy wool).

- Crusts extending from the coronary band to the carpi and hocks.

- Lesions may be fleshy masses (known as strawberry foot rot).

- Seen primarily in UK and Australia.

- Breeds with fine wool such as Suffolk and Romney appear to be more predisposed.

- Loss of economic value due to damage to hide and staining of wool (yellow).

- May occur in conjunction with contagious ecthyma.

- Most common lesions include:

- Goats:

- Crusty lesions are more often seen on the tip of ears and the undersurface of tail of kids. In adults, lesions are typically localized to the following areas: dorsal midline, scrotum, ventral abdomen, and inside the thighs.

- Sheep:

-

-

- It may occur in conjunction with contagious ecthyma (i.e. orf).

-

-

- Llamas:

- Similar crusty lesions develop on the back, sides, and distal extremities.

- Llamas:

-

Diagnosis

- Differential diagnoses include other crusting dermatoses including dermatophytosis, bacterial folliculitis, pemphigus foliaceus (horses and goats), viral infections, and zinc responsive dermatitis.

- Dermatophilosis involving the pastern region, especially of horses, must be differentiated from contact dermatitis (both allergic and irritant), contact photosensitization, atypical dermatophytosis, and pastern folliculitis.

- For sheep, fleece rot (i.e. bacterial skin infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa because of excessive moisture of the skin surface) is also a differential diagnosis.

- Cytology can be diagnostic if performed properly. One or more crusts should be minced and mixed with a few drops of water on a glass slide and allowed to dry. Thereafter, the sample is gram stained (Giemsa stain has been recommended by some) and examined microscopically using the 100x oil objective. Touch impression of fresh exudate under the crust may also be useful.

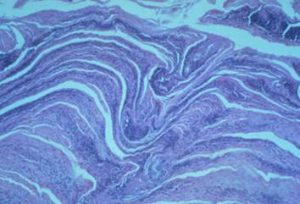

- Dermatophilus congolensis is a gram positive, branching, multiseptate filamentous bacteria, which divide transversally and longitudinally to form cuboidal packets of coccoid cells arranged in two to eight parallel rows within branching filaments. The bacteria arrangement resembles a “railroad track”.

Bacteria arrangement resembling a “railroad track”

-

- In the healing or dry chronic stages of the disease, direct smears are rarely positive.

- Occasionally, it is necessary to culture the organism if the direct microscopic examination is either negative or questionable. The organism grows well on blood agar in a microaerophilic atmosphere with increased carbon dioxide. Report to the laboratory that you are suspecting of dermatophilosis, so the lab can provide the necessary conditions for the organisms to grow.

- Histopathology shows the characteristic “palisading” crust with layers of orthokeratosis, parakeratosis, and inflammatory cells. Dermatophilus organisms can be found embedded in the palisading crust.

-

Therapy

- Horses:

- Although most cases of dermatophilosis will spontaneously regress with the advent of dry weather, certain measures are beneficial.

- Make sure the animal is kept dry.

- Improve the animal’s overall health by providing good nutrition, deworming, and biting insect and arthropod control measures.

- Grooming will remove any of the crusts and should be encouraged but it should be performed carefully to avoid discomfort and additional damage to the skin barrier. Crusts should be disposed of carefully.

- Penicillin G (22,000 IU/kg, IV, twice daily) with or without streptomycin (11 mg/kg) for 7 days seems to help in chronic infections.

- Topical chloramphenicol preparations (0.25-0.5% in cod liver oil) have been recommended for horses with pastern involvement associated with severely crusted and cracked focal lesions.

- Topical treatment options for multifocal to generalized lesions include iodophors, lime sulfur 2-3%, 0.5% zinc sulfate, 0.2% copper sulfate, 1% potassium aluminum sulfate (alum) or chlorhexidine. The recommended protocol involves applying the antiseptic/biocide daily for 3 to 5 days as total body washes, sprays or dips, then weekly. Vinegar has had some reported benefits.

- Previous episodes of dermatophilosis do not lead to significant immunity to re-infection (strain specific). Attempts to immunize animals with several Dermatophilus congolensis antigens were unsuccessful.

- Ruminants:

- Similar to horses, make sure to keep the animals dry and provide good nutrition, deworming, and adequate ectoparasite control.

- Topical treatment is not practical in many circumstances. If possible, lime sulfur 2-3%, iodophors, 0.5% zinc sulfate, 0.2% copper sulfate, and 1% potassium aluminum sulfate should be tried. The latter two have been recommended as preventative or for early treatment.

- Injectable options include a single dose of penicillin G (70,000 IU/kg IM) and 70 mg of streptomycin; daily procaine penicillin G (5,000 IU/kg) and 5 mg/kg streptomycin for 4 to5 days; and a single dose of long-acting oxytetracycline (20 mg/kg). These treatment protocols can be effective in halting outbreaks and allowing change in management.

- Oral organic iodine may be effective in severe cases in cattle.

- Intradermal vaccine has been used only in Africa:

- Reduces incidence and severity of disease.

- In general, unsuccessful in the control and prevention of the disease.

- No immunity to re-infection.

- Change management practice for sheep:

- Do not shear in wet weather.

- Do not dip long fleece.

- Practice tick and ectoparasite control.

- Horses:

Important Facts

- Dermatophilosis is caused by, Dermatophilus congolensis, an actinomycete (filamentous or fungus-like bacteria) organism.

- The two most important factors in the initiation and development of dermatophilosis are skin damage and moisture.

- The disease usually occurs during wet, rainy seasons.

- The typical lesion is a thick crust with a group of hairs embedded in it.

- Consider any crusting dermatosis in large animals to be dermatophilosis until proven otherwise.

- Most cases of dermatophilosis will spontaneously regress with the advent of dry weather. However, make sure to keep the animals dry and provide good nutrition, deworming, and adequate ectoparasite control.

- If treatment is required various topical and systemic treatment protocols have shown to be effective.

References

Scanlan CM, Garrett PD, Geiger DB. Dermatophilus congolensis Infections of cattle and sheep. Comp Cont Educ 1984;6: S 4.

Scheidt VJ, Lloyd DH. Dermatophilosis. In: Robinson NE ed..: Current Therapy in Equine Medicine II. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1986; 630.

Scott DW. Bacterial Diseases. In: Large Animal Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1988; 136-146.White AD. Equine bacterial and fungal diseases: A diagnostic and therapeutic update. Clin Tech Equine Pract 2005; 4:302-310.