3.25 Cutaneous Habronemiasis – Equine

Learning Objectives

- Know what cause habronemiasis in horses and the disease pathogenesis.

- Make a list of differential diagnoses.

- Learn how to diagnose habronemiasis.

- Learn how to manage habronemiasis.

-

General Considerations

- Cutaneous habronemiasis occurs in horses worldwide.

- Disease incidence has decreased with routine use of ivermectin and moxidectin.

- Although the prevalence varies considerably in different parts of the country, cutaneous habronemiasis is a common disease in California and Florida.

- Cutaneous habronemiasis is also commonly called “summer sores” and “swamp cancer.”

-

Cause and Pathogenesis

- Three nematode species are associated with cutaneous habronemiasis:

- Habronema muscae

- Habronema majus

- Draschia megastoma

- The adult nematode resides in the stomach where it causes little reaction with the exception of Draschia megastoma, which produces varying sized nodules that usually occur near the margo plicatus.

- Eggs or larvae, depending on the nematode species, are passed in the host feces.

- The eggs and larvae are ingested by the maggots of the flies, which serve as the intermediate host. Habronema muscae and Draschia megastoma develop in the house fly Musca domestica. Habronema majus develops in the stable fly Stomoxys calcitrans.

- The normal life cycle of these nematodes is completed when the infective larva is deposited by the flies around the horse’s lips where it is subsequently swallowed.

- Cutaneous habronemiasis results from an aberrant parasitism when the nematode larvae gain access to the deeper layers of the skin. Larvae deposited on mucous membranes (vulva, prepuce, eye) or on injured tissues induce a local inflammatory reaction with strong tissue eosinophilia causing cutaneous ‘‘summer sores’’ and/or ophthalmic habronemiasis.

- The infective larvae typically penetrate open wounds and moist areas where flies are feeding; however, larvae can also penetrate healthy skin.

- There is considerable evidence that a hypersensitivity disorder is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. Reasons that support this theory are the following: (i) few horses with wounds develop cutaneous habronemiasis; (ii) disease recurrence is common year after year, typically, in the same horse and (iii) systemic glucocorticoids may be curative as the sole therapy.

- Three nematode species are associated with cutaneous habronemiasis:

-

Clinical Signs

- The disease first appears in the spring and partially or totally resolves in the winter months (larvae do not overwinter in the skin).

- The lesion usually involves the medial canthus of the eye (conjunctiva may also be affected), the male genitalia (especially the urethral process), and the lower extremity (wounds).

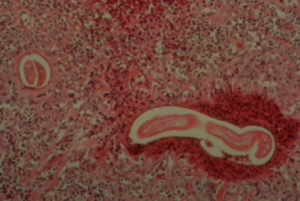

- Lesions consist of areas of ulceration and granulation tissue containing small gritty yellow nodules or granules (they represent necrotic, calcified tissue surrounding the nematode larvae). Lesions may be solitary or multiple.

- Donkeys and mules typically develop very large lesions.

- Pruritus varies from mild to severe.

-

Diagnosis

- The differential diagnoses usually include plain granulation tissue (proud flesh), fibroblastic types of sarcoid, pythiosis, zygomycosis, squamous cell carcinoma, and bacterial granulomas.

- The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous habronemiasis is based on the history, and the location and appearance of the lesions.

- The definitive diagnosis is based on larvae identification via histopathology or semi-nested PCR testing. A deep wedge skin biopsy can be used for both tests. Samples for the PCR test can also be collected through deep scrapings of the skin lesions.

- Impression smears from the surface of lesions or deep scraping of lesions are of little value. However, impressions of the cut surface of biopsy samples can be examined for the presence of eosinophils (eosinophils are also present in pythiosis and zygomycosis).

-

Treatment

- The following goals should be kept in mind:

- Reduce the lesion size.

- Reduce the inflammation.

- Prevent reinfection by eliminating the adult worm and by controlling the vectors.

- Kill the larvae. However, be aware that larval death may be part of the disease pathogenesis.

- Due to the unusual location of the lesions, complete surgical excision is rarely possible.

- Excessive amounts of granulation tissue should be removed.

- Topical therapies to kill the larvae and reduce granulation tissue include:

- Organophosphate containing mixtures:

- Thiabendazole, trichlorfon, DMSO, steroids:

- Habronema ointment used at the University of Tennessee:

- DMSO gel 4 oz

- 43% thiabendazole 150 mg tube

- Azium packets 100 mg

- Trichlorfon 10X10 mg compost paste 6 gm ½ tube

- Furacin Oil 2 oz

- Habronema ointment used at the University of Tennessee:

- Thiabendazole, trichlorfon, DMSO, steroids:

- Organophosphate containing mixtures:

- Ivermectin will kill larvae and adults. Two oral doses at 200 µg/kg administered in a 21-day interval have shown to be effective. However, most animals will need only one dose.

- Due to the recurrent nature of the disease, strict attention to fly control and immediate wound care should be exercised in the future to decrease the chances of re-infection.

- The use of either intralesional or oral corticosteroid (e.g. prednisolone at 1 mg/kg q 24h for 7 to 14 days) to reduce the inflammatory process is an essential part of the treatment regimen and it may be the sole therapy.

- The following goals should be kept in mind:

Important Facts

- Habronemiasis is a disease of horses more commonly seen in California and Florida.

- The disease is caused by the aberrant cutaneous penetration of the infective larvae of three different species of nematodes that parasitize the horse stomach.

- The larvae passed in the horse feces are ingested by the maggots of the flies Musca domestica and Stomoxys calcitrans.

- The larvae can be deposited around the horse’s lips and then be ingested to complete their life cycle or they can be deposited on the surface of previously damaged skin to cause habronemiasis.

- The disease is first seen in the spring.

- Lesions are usually present on the medial canthus of the eye, the male genitalia and lower extremity.

- Few horses with wounds will develop habronemiasis and recurrence in the same animal is common every year indicating the development of a hypersensitivity reaction to larva antigens.

- The definitive diagnosis is based on larvae identification via histopathology or semi-nested PCR testing.

- Three things should be kept in mind when managing this condition: reduce the lesion size, reduce the inflammatory reaction, and prevent reinfection.

- Ivermectin is an effective therapy and kills the nematode adult and larva.

- Glucocorticoid is an essential part of the treatment regimen.

References

Baldacchino F, Muenworn V, Desquesnes M et al. Transmission of pathogens by Stomoxys flies (Diptera, Muscidae): a review. Parasite 2013; 20: 26.

Fadok VA. Parasitic skin diseases of large animals. Vet Clin North Am Large Anim Pract 1984; 6(1):3-26.

Pusterla N, Watson JL, Wilson WD, et al. Cutaneous and ocular habronemiasis in horses: 63 cases (1988–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222: 978–982.

Scott DW. Parasitic Diseases. In: Large Animal Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1988; 251-255.

Traversa D, Iorio R, Petrizzi L et al. Molecular diagnosis of equid summer sores. Veterinary Parasitol 2007; 150(1-2):116-121.

Valentine BA. Equine cutaneous non-neoplastic nodular and proliferative lesions in the Pacific Northwest. Vet Dermatol 2005; 16: 425–428.

van den Top JG, de Heer N, Klein WR, et al. Penile and preputial tumours in the horse: a retrospective study of 114 affected horses. Equine Vet J 2008; 40: 528–532.

Vasey JR. Equine cutaneous habronemiasis. Compend Contin Ed Pract Vet 1981; 3: S290-298.

238: 993-995.