3.4 Canine Sarcoptic Mange

Learning Objectives

- Describe the typical history of a patient with sarcoptic mange.

- Know the characteristic clinical signs of scabies and specially the distribution of lesions.

- Learn how sensitive is skin scraping to diagnose sarcoptic mange.

- Learn the next step if multiple skin scrapings are negative but your index of suspicion for scabies is high.

- Learn the treatment options for sarcoptic mange and the potential side effects associated with the various treatments.

- Learn the recommendations regarding treating the environment and the cat in a household that has a dog with scabies.

-

General Considerations

- Canine scabies or sarcoptic mange is a nonseasonal and intensively pruritic inflammatory skin disease.

- It is highly contagious by contact with infected dogs and, uncommonly, with infested premises, fomites, foxes and coyotes.

- Occasionally, only one dog in a household will have clinical signs. Therefore, lack of contagion should not rule out scabies.

- The incubation period is typically 30 days after a first exposure. However, months can lapse before another dog in the household shows clinical signs.

- Humans exposed to infested dogs can develop clinical signs of scabies. Presented signs are erythematous, pruritic papules on arms, neck and beltline, which usually regress in 12 to 14 days. Signs can persist for longer periods if the numbers of mites are large and contact with the affected animals is prolonged and repeated. Do not rule out scabies if people in contact with diseased pets do not show clinical signs

- It will rarely cause disease in cats because the mite is species specific to some degree.

-

Cause

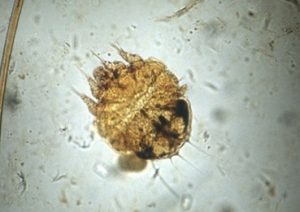

- Sarcoptes scabei var. canis

- The mite spends its entire life cycle on the host.

- The egg-larva-nymph-adult cycle is completed in 17 to 21 days.

- Male mites live on the skin surface while females burrow into the superficial layers of the epidermis to lay eggs.

- At room temperature (68 to 77°F), all stages can survive off the host for 2 to 6 days. Low temperature and high humidity prolong survival.

- Mites in the environment can be point sources of infection for other animals; however, the most important source of infection is the direct contact with the infected dog.

-

Clinical Signs

- No age, sex or breed predilection.

- The hallmark of the disease is PRURITUS. This is one of the most pruritic skin diseases of dogs.

- Pruritus can often be elicited during the examination (i.e. pinnae-pedal reflex – you scratch the lesions on the pinna and the dog moves the hind leg wanting to scratch the pinna). This itching reflex can also be noted when you scrape other affected areas such as the abdomen.

- Pruritus can be caused by:

- Mechanical irritation by the mite (burrowing).

- Pruritogenic substances produced by the mites.

- Hypersensitivity reaction to mite antigens as few numbers of mites can cause generalized pruritus.

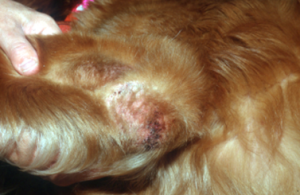

- Lesions are characteristically present at the edge of the pinnae, elbows, hocks, and ventral chest and abdomen. Not always all these areas will be affected in a dog. In chronic cases, the lesions extend to other areas and can become generalized.

-

- Primary lesions are pruritic erythematous papules. Later, these lesions become associated with thick, yellow-gray scales/crusts, especially on the pinnae margins.

-

- Diffuse erythema and multiple papules are the lesions most commonly seen on the ventral chest and abdomen.

-

- Self-inflicted alopecia, lichenification and hyperpigmentation can develop as the disease progresses and becomes chronic.

-

- Excoriations due to severe pruritus are seen. Erythema can become generalized.

- Lymphadenopathy may be present in severe cases.

- Norwegian scabies – very thick, yellow-gray scales/crusts with many mites. It occurs in dogs receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Rare.

-

Diagnosis

- History and clinical signs are very important parts of the diagnosis equation:

- A very pruritic dog non-responsive to corticosteroid therapy.

- Other dogs and people in the same home with suggestive clinical signs.

- Be very suspicious of scabies if you are presented with a middle age to old dog that has never had skin problems and suddenly develops a very pruritic skin condition.

- Do not rule out scabies if other dogs or people in the same home do not show clinical signs at the time you are examining a very itchy dog.

- Classical distribution of lesions – pinnae margins, elbows, hocks, ventral chest and/or ventral abdomen. The disease can generalize in chronic cases.

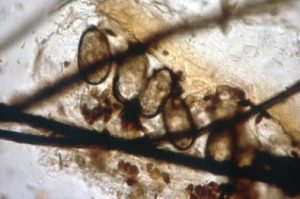

- Skin scrapings:

- The demonstration of mites, ova or feces on multiple skin scrapings is often difficult. Scrapings are negative in about 50% of the cases!

- History and clinical signs are very important parts of the diagnosis equation:

-

-

- Any dog that has classical clinical signs but negative skin scrapings should be treated. Response to appropriate therapy is a diagnostic test. If you suspect it, treat it!

- Multiple broad skin scrapings will increase your chances of finding mites. Scrape until capillary bleeding is obtained. Avoid excoriated areas. Pinna margins and erythematous papules on ventral chest and ventral abdomen are good sites to scrape.

- This is a commonly misdiagnosed disease. Do not miss this curable disease!

-

-

- Pinnae-pedal scratch reflex

- A positive pinnae-pedal-scratch reflex supports your presumptive diagnosis but it is not definitive.

- One study showed a positive predictive value for the pinnae-pedal-scratch reflex of 57% and a negative predictive value of 98%.

- A separate study found that 81.8% of dogs with scabies demonstrated the pinnae-pedal-scratch reflex. The specificity was 93.8%, indicating that rarely other diseases may also result in a positive reflex.

- A serum ELISA test for scabies is available in Europe. Reported sensitivity varies between 84% to 92% and specificity between 90% to 96%. Seroconversion can take up to 5 weeks. Detectable antibodies disappear within 30 days of treatment.

- Pinnae-pedal scratch reflex

-

Treatment

- Remember! You cannot use results of skin scrapings to determine the duration of therapy (the rule of thumb used for canine follicular demodicosis) because mites are not consistently found on skin scrapings.

- Isoxazolines – The drugs in this class are the first treatment choice of the authors because they are effective, generally safe and easy to administer. The main concerning, but uncommon, side effect is seizure. Do not use these drugs in dogs with a history of seizures.

- Afoxolaner (NexGard™; Merial): A randomized controlled trial showed significant decrease in mite numbers and clinical signs after treatment of 67 dogs with afoxolaner administered orally on days 0 and 28. It was given at the same dose protocol recommended for the treatment of flea and tick infestations. No mites were found on multiple skin scrapings on days 28 and 56. Pruritus was absent on days 28 and 56.

- Sarolaner (Simparica™; Simparica Trio™; Zoetis). A randomized controlled trial showed the efficacy of sarolaner for the treatment of canine scabies given at the same dose recommended for the control of fleas and ticks. The dogs received two doses at 30-day interval. After 60 days of therapy, there were no mites found on multiple skin scrapings and pruritus had resolved in the large majority of dogs. Another randomized controlled trial showed that two monthly doses of Simparica Trio® (sarolaner + moxidectin + pyrantel) was very effective to treat scabies in dogs. The dose recommended by the manufacturer to treat flea and tick infestations was used in the trial.

- Fluralaner (Bravecto™; Merck). A study showed the efficacy of fluralaner for the treatment of 17 dogs with scabies. Fluralaner was given once at the same dose protocol recommended for the treatment of flea and tick infestations. No mites were found after 14 days of therapy and significant improvement in pruritus and skin lesion scores were noted between days 14 and 21 of the study. Another study evaluated the efficacy of fluralaner administered orally and topically once at the same dose used for tick and flea control. No mites were seen after 4 weeks and significant decrease in clinical signs, including pruritus, was noted at week 4.

- Lotilaner (Credelio™; Elanco GmbH): Eight dogs with scabies were treated successfully with lotilaner at the dose recommended by the manufactur. The dogs received three monthly doses. Pruritus resolved in 14 days and skin lesions resolved after two months.

- Ivermectin (Ivomec®; Merial) at 300 to 400 µg/kg (0.3 to 0.4 mg/kg) orally for three doses at 1-week intervals or subcutaneously at 2-week intervals for three treatments. When performing a treatment trial to rule out scabies in cases with negative skin scrapings, expect improvement in 10 to 14 days after the first ivermectin treatment because most dogs respond within this period of time. If no significant improvement is noted, give the second dose and if still no improvement reconsider your diagnosis.

- Do not use ivermectin in the following breeds: collie, Shetland sheepdog or their crosses; Australian shepherd; white Swiss shepherd, longhaired whippet, silken windhound, McNab, and Border collie dogs. Breeds that the allele for the mutated ABCB1 gene has been detected but no homozygote for the mutated has been reported include old English sheepdogs, Waller, and the English shepherd. Ideally, avermectins should not be used in these breeds. Currently, there is a genetic test available at the Washington State University (https://vcpl.vetmed.wsu.edu/) that can identify the ABCB1- 1 gene mutation associated with avermectin toxicity. This gene encodes for P-glycoprotein, which is responsible for pumping-out substances that cross the blood-brain barrier.

- Milbemycin oxime (Interceptor™; Elanco). One study showed 98-100% success with 1 mg/kg of milbemycin oxime given orally q 48h for eight treatments or 2 mg/kg, orally, twice weekly for three consecutive weeks. Another protocol is 2 mg/kg, orally, once weekly for four weeks. However, failure has been reported with this protocol and the recommendation is to extend treatment to six to eight weeks. It can be used in “ivermectin-sensitive breeds” but do not use doses higher than 2 mg/kg and monitor closely for potential side effects. Ideally, test for the ABCB1-1 mutation and if the dog is homozygous for the mutation consider another treatment option.

- Selamectin (Revolution®; Zoetis): This is a licensed drug for the treatment of scabies in the U.S. The labeled dosage of one application every 30 days for two treatments is used. However, for best results most dermatologists recommend one application every 2 weeks for four treatments. In ivermectin sensitive breeds, apply it four times at a 30-day interval. In some cases, improvement may only be noticed after the third application.

- Imidacloprid 10%/moxidectin 2.5% spot-on (Advantage Multi™, Bayer Health Care): A dose of 0.1 mL/kg applied twice at a 4-week interval has been approved for the treatment of scabies. However, three treatments applied every 3 weeks has been anecdotally reported as more efficacious. Significant decrease in pruritus may not be seen before the second or third treatment.

- Fipronil (Frontline® Spray; Merial): Spray to soak the skin and hair coat two to three times at 2-week intervals (dogs and cats). Do not use this product if doing a treatment trial because it has been associated with failure and you may erroneously rule out the disease if the treatment does not work. DO NOT USE FIPRONIL IN RABBITS. IT HAS BEEN ASSOCIATED WITH FATALITY.

- Must treat all in-contact dogs and the environment (premises flea spray). Discard bedding. Cats are rarely infested with Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis. Only treat cats if they show clinical signs.

- Oclacitinib (Apoquel®; Zoetis) at the doses of 0.5 mg/kg q 12h for 14 days followed by 0.5 mg/kg q 24h for 14 days was very effective in reducing pruritus in 31 dogs with scabies. A significant decrease in pruritus was reported by pet owners within 24h of the first dose. This report suggests that oclacitinib can be used to alleviate the pruritus associated with scabies until the effect of the parasiticidal is noted.

Important Facts

- Canine scabies is a very pruritic skin condition.

- Pinnae margins, elbows, hocks, ventral chest and ventral abdomen are the body sites typically affected.

- It is contagious to other dogs and people, however, do not rule out scabies if dogs and people in the same household do not show clinical signs.

- Be suspicious of scabies if a pruritic dermatosis is steroid responsive.

- Be suspicious of scabies if a middle age to old dog develops a severely pruritic skin condition for the first time.

- Skin scrapings are negative in about 50% of the cases.

- If you suspect it, treat it!

- Treat all dogs in the house and treat the environment.

References

Becskei C, Liebenberg J, Fernandes T, et al. Efficacy of a chewable tablet containing sarolaner, moxidectin, and pyrantel (Simparica Trio®) in the treatment of sarcoptic mange caused by Sarcoptes scabiei mite infestations in dogs. Parasit Vectors 2023; doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-06049-9.

Becskei C, De Bock F, Illambas J, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel oral isoxazoline, sarolaner(SimparicaTM), for the treatment of sarcoptic mange in dogs. Vet Parasitol 2016; 222: 56-61.

Cornegliani L, Guidi E, Vercelli A. Use of oclacitinib as antipruritic drug during sarcoptic mange infestation treatment. Vet Derm 2020; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12920.

Hampel V, Knaus M, Schafer J, et al. Treatment of canine sarcoptic mange with afoxolaner (NexGard) and afoxolaner plus milbemycin oxime (NexGard Spectra) chewable tablets: efficacy under field conditions in Portugal and Germany. Parasite 2018; 25:63.

Hawkins JA, McDonald RK, Woody BJ. Sarcoptes scabiei infestation in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 190: 1572-1573.

Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Small Animal Dermatology, 7th edn. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2013; 315-319.Becskei C, De Bock F, Illambas J, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel oral isoxazoline, sarolaner (SimparicaTM), for the treatment of sarcoptic mange in dogs. Vet Parasitol 2016; 222:56-61.

Moog F, Brun J, Bourdeau P, et al. Clinical, parasitological, and serological follow-up of dogs with sarcoptic mange treated orally with lotilaner. Case Rep Vet Med 2021; doi.org/10.1155/2021/6639017.

Romero C, Heredia R, Pineda J, et al. Efficacy of fluralaner in 17 dogs with sarcoptic mange. Vet Derm 2016; 27:353-e88.

Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE. Small Animal Dermatology. 5th edn. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1995; 434-441.

Taenzler J, Liebenberg J, Roepke R et al. Efficacy of fluralaner administered either orally or topically for the treatment of naturally acquired Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis infestation in dogs. Parasit Vectors 2016; 9:392.