1.1 Canine Pyodermas

Learning Objectives

- What is the most common bacteria cultured from canine pyodermas?

- Considering that canine pyoderma is usually a secondary problem, what are the underlying conditions associated with canine pyodermas?

- What are the dermatoses classified under surface, superficial and deep pyodermas?

- How do you manage “hotspots”?

- In what circumstances should you perform culture and susceptibility when managing a canine pyoderma case?

- What antibiotics should you not use when managing empirically a canine pyoderma?

- Cite four antibiotic options used to treat canine pyodermas.

- How long do you treat a superficial pyoderma?

- How long do you treat a deep pyoderma?

-

General Considerations

- Main physical, physiologic, immunologic and microbial defense mechanisms against pathogenic bacteria :

- Physical: Hair coat and stratum corneum.

- Physiological: Epidermal turnover with exfoliation and epidermal lipids (fatty acids present in sebum have a bacteriostatic and fungistatic effect).

- Immunological: Immune cells, immunoglobulins, interferon, defensins and other antimicrobial peptides.

- Microbial: Normal nonpathogenic skin bacterial flora and other microorganism inhabiting the skin – The Skin Microbiome.

- Pyodermas should always be considered a secondary problem that complicates an underlying primary skin disease. Any skin disease can potentially alter one or more of the listed cutaneous defense mechanisms and open the door for the development of pyoderma. Rarely, a predisposing condition will not be identified. The pyoderma is then called: “idiopathic, primary, recurrent, superficial pyoderma”. It is important to educate the pet owner at the initial visit that an underlying primary skin disease is presdisposing the pet to develop the pyoderma and this disease needs to be identified and properly treated to prevent recurrences.

- Examples of common predisposing conditions include:

- Allergic diseases (atopic dermatitis, food allergy, flea bite allergy, contact allergy).

- Endocrinopathies (hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism, sex hormone imbalances).

- Poor nutrition status.

- Immunologic incompetence (sometimes related to neoplasia).

- Primary keratinization defects.

- Ectoparasites (demodicosis, scabies, cheyletiellosis, pediculosis).

- Anatomic defects (e.g. skin folds).

- Inappropriate prior therapy such as excessive and long-term use of glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive drugs.

- Trauma

- Environmental factors (high temperature and humidity).

- Abnormal weight bearing on feet due to musculoskeletal problems leading to the formation of comedonic and cystic hair follicles that eventually rupture (furunculosis) and cause chronic inflammation and deep infection.

- Main physical, physiologic, immunologic and microbial defense mechanisms against pathogenic bacteria :

-

Definition

- Pyoderma means “pus in the skin”, therefore, by strictest definition a pyoderma is any pus-producing bacterial skin disease. However, in a clinical setting the pustular or purulent lesion may not be present macroscopically. Therefore, for practical purposes pyoderma is a bacterial infection within the skin associated or not with pus-producing lesions.

-

Causes

- Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (formerly known as S. intermedius) is by far the most common pathogen in canine pyoderma (found in more than 90% of the cases).

- Staphylococcus aureus, S. coagulans, and S. schleiferi are found in a low number of cases. Staphylococcus schleiferi and S. coagulans are often a cause of canine otitis externa.

- Gram-negative bacteria such as Proteus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli may be found as primary causes or secondary invaders, especially, of deep pyoderma. These agents can also be found as causes of otitis.

Important Facts

- Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (previously S. intermedius), S. coagulans, S. schleiferi and S. aureus produce B-lactamase.

- B-lactamase destroys penicillin, amoxicillin, and ampicillin. In addition, S. pseudintermedius, S. coagulans, S. schleiferi , and S. aureus strains are often resistant to streptomycin and tetracycline.

- Do not empirically use these antibiotics to manage canine pyoderma.

- If systemic antibiotic is needed, the selection should be, ideally, based on culture and susceptibility test results and a “first choice drug” should be prescribed.

- “First choice drugs” include: clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

-

Classification of Pyoderma

- Primary or secondary: most pyodermas are secondary to an underlying primary skin disease, a systemic disease or a factor; therefore, consider most bacterial skin infections secondary until proven otherwise.

- Site: used to denote specific regional dermatoses caused by bacterial infection (e.g.: nasal pyoderma, interdigital pyoderma).

- Pathogen: used when it is caused by an unusual pathogen(i.e. nocardiosis, atypical mycobacteriosis).

- Depth of infection (i.e. superficial versus deep): a useful classification scheme because therapy is often based on depth of infection.

- Depth of infection: This classification will be used here because it best relates to treatment recommendations.

- Surface “pyoderma”: pyoderma is listed here in quotations because the diseases in this category do not constitute a true bacterial infection but, bacterial overgrowth/colonization after the skin barrier is disrupted. Only the most superficial layers of the epidermis are involved.

- Pyotraumatic dermatitis (acute moist dermatitis, “hot spot”).

- Skin fold pyodermas or intertrigo.

- Superficial pyoderma: the bacteria infection involves the primarily the hair follicles but also the epidermis:

- Impetigo (juvenile form [puppy pyoderma], adul form [bullous impetigo]).

- Bacterial folliculitis.

- Deep pyoderma: the bacterial infection involves tissues deeper than the hair follicle (typically associated with rupture of hair follicles [i.e. furunculosis]):

- Chin pyoderma (acne).

- Nasal pyoderma.

- Interdigital pyoderma.

- Generalized deep pyoderma (bacterial furunculosis/cellulitis).

- Deep “hotspot” (pyotraumatic folliculitis/furunculosis).

- Post-grooming furunculosis

- Surface “pyoderma”: pyoderma is listed here in quotations because the diseases in this category do not constitute a true bacterial infection but, bacterial overgrowth/colonization after the skin barrier is disrupted. Only the most superficial layers of the epidermis are involved.

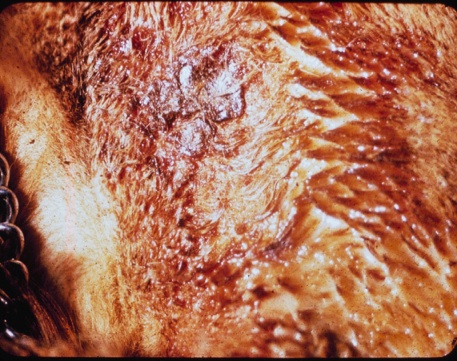

- Surface Pyoderma – Pyotraumatic Dermatitis (a.k.a. acute moist dermatitis, “hot spot”)

- Etiology: self-inflicted. Underlying problems cause the dog to lick, chew, and/or scratch. The trauma to the skin leads to mechanical removal of the stratum corneum resulting in exudation and secondary bacterial infection.

- Occurs especially in dogs with thick, long hair coats (e.g. Saint Bernards, golden retrievers etc) because water/moisture more readily accumulates on the skin surface. This leads to maceration (softening) of the stratum corneum, which facilitates the stratum corneum removal resulting in exudation and secondary bacterial infection.

- More common in hot, humid weather.

- Rapid onset.

- Common underlying diseases or initiating factors:

- Allergic skin diseases (flea allergy, atopic dermatitis, food allergy).

- Ectoparasites or pruritic ectoparasitic diseases (e.g. scabies, cheyletiellosis).

- Anal sac disease.

- Otitis externa.

- Bacterial folliculitis (often pruritic).

- Trauma, minor wounds.

- Dirty, matted hair coat.

- Foreign body trapped on the hair — can directly cause skin damage or prompt the dog to itch.

- Clinical Signs: self-trauma causes erythema, erosion, edema and serous-purulent exudate which covers the lesion surface and forms a thin yellow-brown crust when it dries. The lesion is painful and it is usually well demarcated and worsened by patient’s licking, chewing and scratching. Exudate is trapped in the haircoat and the lesion spreads peripherally.

-

-

- Diagnosis:

- History including signalment and clinical signs.

- Try to identify the underlying primary cause.

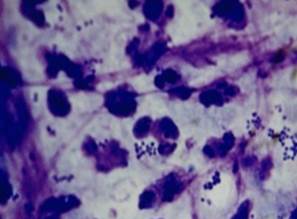

- Perform a cytologic exam. You should find cocci and degenerated neutrophils.

- Treatment:

- Treat the underlying primary disease to prevent or reduce the frequency of recurrences!

- Treat the lesion:

- Clip and remove matted hairs.

- Clean (e.g. dilute chlorhexidine).

- Topical corticosteroid/antibiotic cream or ointment work well because of the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. Use any topical product that contains glucocorticoids carefully to avoid skin atrophy, which could lead to systemic signs of hypercortisolism if the treated area is extensive and the glucocorticoid is applied for long periods of time. Avoid topical glucocorticoid products that contain alcohol; alchhol can dry the skin and cause irritation on an already inflamed skin.

- Systemic antibiotics may be necessary in cases associated with generalized bacterial infection (bacterial folliculitis) where topical therapy is not effective as sole therapy. If systemic antibiotic is required, perform a bacterial culture and susceptibility test and select a “first choice drug”, which includes clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid. Refer to “General Information Related to the Management of Pyoderma” in this section for more details regarding the use of systemic antibiotic.

- Diagnosis:

-

Important Facts

- Pyotraumatic dermatitis or acute moist dermatitis or “hot spot” is self-induced.

- Always look for an underlying primary condition and treat it properly to prevent recurrences.

- Dogs with thick and long hair coats will often develop “hot spots” during hot and humid weather.

- It is recommended to treat this condition topically.

-

- Surface Pyoderma – Skin Fold Pyodermas

- Pathomechanism: areas of skin folds, characteristic of certain breeds, predispose to maceration of the stratum corneum and bacterial overgrowth because of:

- Constant skin rubbing/friction.

- Poor air circulation.

- Accumulation of moisture from secretions and excretions (sebum, tears, saliva, urine).

- All skin fold pyodermas are characterized by exudative, odiferous, and erythematous lesions within skin folds:

- Lip fold pyodermas:

- Pathomechanism: areas of skin folds, characteristic of certain breeds, predispose to maceration of the stratum corneum and bacterial overgrowth because of:

- Surface Pyoderma – Skin Fold Pyodermas

-

-

-

-

-

- Lower lip folds in cocker and springer spaniels, setters and Saint Bernard dogs (other breeds can also be affected).

- Client complaint is usually severe halitosis.

- Treatment:

- Surgical ablation (cheiloplasty) offers the potential for permanent cure and should be considered in recurrent cases.

- Palliative therapy consists of clipping the hair, gentle daily cleansing with an antiseptic solution such as, diluted chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, or diluted hydrogen peroxide. Topical corticosteroid, antibiotic and/or antifungal cream or solution to treat the inflammation and infection (e.g. ophthalmic products are good options but expensive; various otic products).

- After the surface pyoderma is resolved, long-term regular therapy (i.e. at lest once weekly) to prevent recurrences is necessary. This consists of regular treatment of the area with wipes, pads, mousses or sprays containing chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, 2% acidic acid and 2% boric acid. Ear cleaning products containing organic acids such as, lactic acid, salicylic acid, acetic acid, boric acid, malic acid and benzoic acid can also be used and work well.

- Facial fold pyodermas:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Folds between eyes and nose in brachycephalic breeds (e.g. Boston terrier, bull dog, Pekingese, Pug, etc).

- Concurrent traumatic corneal abrasions or ulcerations are common and the associated epiphora will result in moisture accumulation in the folds leading to intertrigo.

- Treatment:

- Surgical ablation offers the potential for permanent cure and should be considered in recurrent cases (Note: absence of facial fold is considered a serious defect in show dogs).

- Palliative therapy consists of gentle daily cleansing with an antiseptic solution such as, chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, or diluted hydrogen peroxide. Topical corticoisteroid, antibiotic and/or antifungal cream or solution to treat the inflammation and infection (e.g. ophthalmic products are good options; various otic products).

- After the surface pyoderma is resolved, long-term regular therapy (i.e. at lest once weekly) to prevent recurrences is necessary. This consists of regular treatment of the area with wipes, pads, mousses or sprays containing chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, 2% acidic acid and 2% boric acid. Ear cleaning products containing organic acids such as, lactic acid, salicylic acid, acetic acid, boric acid, malic acid and benzoic acid can also be used and work well.

-

-

- Vulvar fold pyodermas:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Obese females which may have been spayed before the first estrus are more prone to this disorder. Vulvas are recessed, infantile.

- Client complaint is usually excess licking at vulva, foul odor and painful urination.

- Clinical signs may include perivulvar erosions to ulcerations and reluctance to having the affected area examined.

- Secondary ascending urinary tract infection may occur.

- Treatment:

- Surgical ablation (episioplasty) offers the potential for permanent cure and should be considered in recurrent cases.

- Palliative therapy consists of clipping the hair, gentle daily cleansing with an antiseptic solution such as chlorhexidine or diluted hydrogen peroxide. Topical corticoisteroid, antibiotic and/or antifungal cream or ointment to treat the inflammation and infection is very important. If significant erosion or ulceration is present, a short course of oral glucocorticoid (e.g. prednisone) at anti-inflammatory doses will be necessary.

- After the surface pyoderma is resolved, long-term regular therapy (i.e. at lest once weekly) to prevent recurrences is necessary. This consists of regular treatment of the area with wipes, pads, mousses or sprays containing chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, 2% acidic acid and 2% boric acid. Ear cleaning products containing organic acids such as, lactic acid, salicylic acid, acetic acid, boric acid, malic acid and benzoic acid can also be used if erosions or ulcerations have resolved.

- Weight reduction if obese.

- Oral prednisone if the skin is eroded or ulcerated (0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg q 24hrs for 10 to 14 days on a reducing schedule).

-

- Tail fold pyoderma:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- It occurs in breeds with “corkscrew tails” such as English bulldogs, Boston terriers, Pugs, etc.

- Treatment:

- Surgical amputation or reconstruction offers the potential for permanent cure. These cases can be challenging to treat medically and most will require surgery.

- Palliative therapy consists of gentle daily cleansing with an antiseptic solution such as chlorhexidine or diluted hydrogen peroxide. A topical corticoisteroid, antibiotic and/or antifungal cream or solution to treat the inflammation and infection (e.g. ophthalmic products, otic products) is often needed for moderate to severe cases.

- After the surface pyoderma is resolved, long-term regular therapy (i.e. at lest once weekly) to prevent recurrences is necessary. This consists of regular treatment of the area with wipes, pads, mousses or sprays containing chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, 2% acidic acid and 2% boric acid. Ear cleaning products containing organic acids such as, lactic acid, salicylic acid, acetic acid, boric acid, malic acid and benzoic acid can also be used and work well.

-

-

-

Important Facts

- All skin fold pyodermas are exudative, odiferous and erythematous lesions within skin folds localized on or around the lip, face, vulva and tail.

- Surgical ablation of the affected fold offers potential for permanent cure and should be considered in recurrent cases where the skin fold is not a breed characteristic.

- It is recommended to treat this condition topically.

-

- Superficial Pyoderma – Impetigo (juvenile form [puppy pyoderma], adult form [bullous impetigo])

- Lesions develop in sparsely haired skin (groin, abdomen, and axillae) in the juvenile form but often develops along the dorsum in the adult form. The juvenile form affects dogs less than 1 year old. The adult form develops in middle age to old dogs.

- In the juvenile form, lesions include pustules, papules, honey-colored crusts, and epidermal collarettes. The adult form typically presents with large and flacid pustules and/or honey-colored crusts. Pruritus may be present in some cases.

- Superficial Pyoderma – Impetigo (juvenile form [puppy pyoderma], adult form [bullous impetigo])

-

-

- The juvenile form is often seen in healthy dogs without any identifiable associated condition. However, it may develop in dogs with endo- or ectoparasitism, poor nutrition, dirty environment, and viral infections (distemper).

- The adult form typically develops in immunocompromised dogs.

- Diagnosis:

- History and clinical signs.

- Cytologic exam – degenerated neutrophils and intra- and extra-cellular cocci bacteria.

- Treatment:

- No treatment may be required for the juvenile form if lesions are mild and the dog is otherwise healthy. In these cases, the disease is usually self-limiting.

- If treatment is necessary, topical therapy is recommended such as, antibacterial shampoos (e.g.: benzoyl peroxide, chlorhexidine, ethyl lactate, acetic acid + boric acid); sprays, wipes and mousses containing antiseptics such as chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid and organic acids (e.g. salicylic acid, malic acid, acetic acid, lactic acid etc.). An antibacterial ointment may be needed for persistent cases. Make sure to search for an underlying factor (e.g. poor nutrition, end/ecto parasites etc) and address it. Maintain general health care.

- It is crucial to identigy and address the condition leading to immunodeficiency in adult dogs with bullous impetigo. As for the juvenile form, topical treatment should be tried first. In these cases, not only topicals containing antiseptics but also an antibiotic cream or ointment will likely be needed. If topicals are not effective as sole therapy, if the disease is widespread or if there are patient or client limitations (e.g. owner cannot apply, aggressive dog, lack of facilities etc), systemic therapy will be required. Ideally, the antibiotic should be selected based on culture and susceptibility and “first choice drugs” such as, clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid should be prescribed. If the antibiotic is selected empirically only the “first choice drugs” should be prescribed. Refer to “General Information Related to the Management of Pyoderma” in this section for more details regarding the use of systemic antibiotic.

- Remember! Pyoderma should be considered a secondary problem until proven otherwise. Therefore, it is very important to explain to the pet owner during the first visit that the underlying primary disease needs to be identified and treated properly to prevent recurrences.

-

Important Facts

- Pustules, papules, crusts and epidermal collarettes in sparsely haired skin of the groin, abdomen and axillae are the signs of juvenile impetigo.

- Large and flacid pustules typically along the dorsum are the signs of bullous impetigo in immunodeficient adult dogs.

- Treatment of impetigo usually only requires topical therapy.

- If systemic therapy is needed, perform culture and susceptibility test. If culture and susceptibility cannot be done, select a “first choice antibiotic”, which include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

- It is crucial to look for an underlying primary disease or factor and treat it properly to prevent or reduce the frequency of recurrences.

-

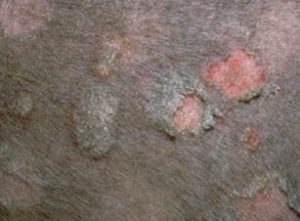

- Superficial Pyoderma – Bacterial Folliculitis

- Bacterial folliculitis is a bacterial infection limited to the hair follicle. Most cases of superficial bacterial skin infection in dogs are associated with the hair follicle.

- Bacterial folliculitis is considered the most common form of canine bacterial skin infection, as it will eventually develop in almost every skin disease.

- Clinical signs:

- Any breed:

- Papules, pustules, erythema, epidermal collarettes, circumscribed areas of alopecia with or without central pigmentation.

- Any breed:

- Superficial Pyoderma – Bacterial Folliculitis

-

-

-

-

- Pruritus may be non-existent to intense.

- Short-coated breeds:

- “Moth-eaten” alopecia (can mimic ringworm and follicular demodicosis).

- Some dogs will develop papules, pustules, and/or crusting.

- It is not uncommon to see short-coated breeds with small tufts of hair standing up in areas of bacterial folliculitis.

- Pruritus may or not be present. If present, it will aggravate the pruritus associated with pruritic underlying diseases such as, atopic dermatitis, or be a complicating sign of a non-pruritic underlying disease such as, hypothyroidism.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Pathogenesis of pruritus:

- Most likely caused by large numbers of infiltrating inflammatory cells (mainly neutrophils), which release pruritogenic substances such as, proteases.

- True bacterial hypersensitivity reactions have not been well documented.

- Distribution on the body:

- Usually trunk, ventral abdomen, and inner thighs.

- Rarely affects the face, pinnae or distal extremities; if these sites are affected, re-evaluate your diagnosis.

- Pathogenesis of pruritus:

-

-

- Bacterial folliculitis is usually secondary to an underlying primary disease.

- Bacterial folliculitis can be a recurrent problem if the underlying primary condition is not identified and treated properly, if the underlying condition is chronic, or if it doesn’t respond well to the appropriate treatment protocol.

-

-

Important Facts

- Bacterial folliculitis is typically secondary to an underlying primary disease.

- Address the underlying disease to prevent or reduce the chances for frequent recurrences.

- It can present as one or more of the following lesions: papules, pustules, epidermal collarettes, crusts and moth-eaten alopecia.

-

-

- The underlying diseases associated with bacterial folliculitis can be classified into pruritic and non-pruritic diseases.

- Pruritic diseases –“the itch that rashes” (if pruritus is present before skin lesions associated with pyoderma develop, or if pruritus remains after the existing pyoderma has resolved with appropriate therapy):

- Atopic dermatitis.

- Food allergy.

- Flea allergy.

- Sarcoptic mange.

- Cheyletiellosis.

- Demodex mange caused by Demodex injai.

- Non-pruritic diseases – “the rash that itches” (if pruritus occurs after the skin lesions associated with pyoderma develop, or if pruritus disappears when the pyoderma resolves):

- Hypothyroidism.

- Hyperadrenocorticism.

- Sex hormone imbalances.

- Follicular dysplasias.

- Primary keratinization disorders.

- Follicular demodicosis caused by Demodex canis.

- Pruritic diseases –“the itch that rashes” (if pruritus is present before skin lesions associated with pyoderma develop, or if pruritus remains after the existing pyoderma has resolved with appropriate therapy):

- The underlying diseases associated with bacterial folliculitis can be classified into pruritic and non-pruritic diseases.

-

Important Facts

- Bacterial folliculitis is a common complication of underlying primary skin disorders.

- It is considered the most common form of canine bacterial skin infection because it will eventually develop in almost every skin disease.

- If the primary disease is successfully managed, the chances for recurrences will likely decrease.

-

-

- Differential diagnoses for bacterial folliculitis:

- Follicular demodicosis (moth-eaten alopecia, papules, pustules, crusts).

- Dermatophytosis (moth-eaten alopecia, epidermal collarettes, pustules, crusts).

- Pemphigus foliaceus (pustules, crusts, papules).

- Differential diagnoses for bacterial folliculitis:

-

Important Facts

- If a lesion in a dog looks like ringworm, it is probably a bacterial folliculitis manifesting as epidermal collarettes, or moth-eaten alopecia.

-

-

- Diagnosis:

- History and clinical signs.

- Skin scrapings – important to rule in parasitic diseases as underlying causes.

- Cytology of pustules and/or exudate underneath a crust (cocci bacteria and degenerated neutrophils).

- Culture for ringworm – perform in cases with history and clinical signs suggestive of dermatophytosis.

- Biopsy: rarely necessary.

- Response to therapy. Use the proper antibiotic, in the proper dose, for the proper period of time. Evaluate the response to therapy yourself (i.e. recheck).

- Treatment: For more details refer to “General information related to the management of pyodermas” below

- Identify and treat any underlying primary skin disease.

- Always consider the use of topical therapy (i.e. antiseptics and topical antibiotic) as sole therapy before prescribing systemic antibiotic to treat bacterial folliculitis. Photobiomodulation using fluorescent light energy (e.g. Phovia™; Vetoquinol) has been shown to resolve bacterial folliculitis when applied as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic or as sole therapy (refer to “General information related to the management of pyoderma” below for details).

- If the infection is extensive, solely topical therapy is not effective, or there are limitations to the use of topical therapy, systemic antibiotic will likely be required.

- Use the proper antibiotic, in the proper dose, for the proper period of time. Ideally bacterial culture and susceptibility should be performed in all cases. If it is not possible, perform culture and susceptibility in the following circumstances: (i) recurrent bacterial folliculitis, (ii) new lesions developing during treatment, (iii) deep pyoderma, (iv) when cytology reveals rod-shaped bacteria, (v) any time there has been poor response to empirical therapy and (vi) history of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) and multi-drug resistant (MDR) infections.

- Proper antibiotic: Select the “first choice drugs” whenever possible and independent if the antibiotic selection is based on bacterial culture and susceptibility (ideally) or empirical. First coice antibiotics include: clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

- Treatment duration: Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy and treat bacterial folliculitis until complete resolution of all skin lesions. Typical duration of therapy for first time infection: 2 to 3 weeks. Plan to schedule the first recehck visit in 2 weeks.

- If systemic antibiotic is required, shampoos, mousses and srays containing antiseptics such as, chlorhexidine and hypochlorous acid, should be used concurrently and as frequently as daily in some cases. These treatments should be instituted at least once weekly as maintenance therapy to help prevent recurrences.

- Diagnosis:

-

Important Facts

- Always consider solely topical therapy (i.e. antiseptics and topical antibiotic) before prescribing systemic antibiotic, especially, when the infection is mild and localized.

- If systemic antibiotic is required, use the proper antibiotic (i.e. “first choice dogs”) in the proper dose until complete resolution of clinical signs.

- “First choice drugs” include: clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

- If treating with systemic antibiotic, add topical therapy with antiseptics to the treatment regimen to reduce the duration of therapy.

- Maintenance therapy with antiseptics (e.g. chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid etc.) is important to help prevent recurrences.

-

- Deep Pyoderma – Canine Acne

- The pathomechanism of canine acne is not well understood. However, it likely starts with a bacterial folliculitis, which typically involves various hair follicules. Eventually, affected follicles rupture (known as furunculosis). When furunculosis occurs, fragments of hair shafts and bacteria are exposed to the dermis and act as foreign bodies attracting large numbers of inflammatory cells. In an attempt to expel the hair fragments and bacteria, draining tracts are formed.

- Canine acne occurs more often in short-coated breeds.

- It typically starts at a young age (3 to 12 months) but may persist throughout adulthood. It can also start in dogs older than 1 year of age.

- Clinical signs:

- Erythematous papules, nodules, and/or hemorrhagic bullae develop on chin but can extent to the lip margins and upper muzzle. With time, papules and nodules erode or ulcerate. Draining tracts are formed to eliminate hair shaft fragments and bacteria lodged in the dermis after the rupture of hair follicles. These tracts discharge a sanguineo-purulent exudate (suppurative folliculitis or furunculosis present).

- Deep Pyoderma – Canine Acne

-

-

-

- Differential diagnosis:

- Localized demodicosis associated with furunculosis.

- Juvenile cellulitis if acne cases are severe/extensive; however, this is a sterile disease that can be secondarily infected. Juvenile cellulitis typically affects dogs less than four months of age and is characterized by the presence of edema, papules, nodules and draining tracts localized to the muzzle, chin and perioccular region. Other areas of the body are also typically affected such as the concave aspect of the pinnae and mucocutaneous junctions. Lymphadenomegaly is a hallmark of the disease.

- Diagnosis:

- History and clinical signs.

- Skin scrapings to rule out demodicosis.

- Cytology of exudate from draining tracts and/or erosions/ulcers and exudate underneath a crust (a few cocci, degenerated neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, +/- eosinophils).

- Biopsy: rarely necessary.

- Treatment:

- None if mild.

- Periodic cleaning with benzoyl peroxide shampoo (reduces the surface bacterial population and keeps the hair follicle open) and wipes or mousse containing a antisepts such as, chlorhexidine or hypochlorous acid. Be careful, as overuse of benzoyl peroxide can irritate the skin and aggravate the existing condition.

- Systemic antibiotic only if severe. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy and deep infections should be treated until complete resolution of all skin lesions. Choose antibiotic therapy for deep pyoderma based on culture and susceptibility results. Select the “first choice drugs” whenever possible. They include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid.

- Topical antibiotic: mupirocin ointment (save this treatment for cases of methicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections) or ointments that contain a glucocorticoid and antimicrobials (e.g. ophthalmic or otic products).

- Photobiomodulation using fluorescent light energy (e.g. Phovia™; Vetoquinol) has been shown to resolve deep pyoderma when applied as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic or as sole therapy (refer to “General information related to the management of pyoderma” below for details).

- Differential diagnosis:

-

- Deep Pyoderma – Nasal Pyoderma

- Uncommon, but seen more often in German shephard dogs, collies, pointers and hunting-type dogs.

- Rapid onset.

- Clinical signs:

- Erythematous papules, nodules, and/or hemorrhagic bullae develop. With time, papules and nodules erode or ulcerate. Draining tracts are formed to eliminate hair shaft fragments and bacteria after the rupture of hair follicles. These tracts discharge a sanguineo-purulent exudate (suppurative folliculitis or furunculosis present). Crusting is often formed after the exudate dries out.

- Lesions typically occur at the dorsal aspect of the nose and the area around the nostrils.

-

-

-

-

- Differential diagnoses:

- Dermatophyte infections (ringworm) associated with rupture of hair follicles (kerion = very inflamed lesion associated with draining tracts).

- Facial eosinophilic furunculosis. Think of this condition if large numbers of eosinophils are present on cytology.

- Diagnosis:

- History and clinical signs.

- Cytology of exudate from draining tracts and/or ulcers and exudate underneath a crust (a few cocci, degenerated neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, +/- eosinophils).

- Trichogram to try to rule in dermatophytosis (look for arthrospores and hyphae around the hair shaft, positive in about 50% of cases).

- Fungal culture if highly suspicious of dermatophytosis.

- Skin biopsy to rule out facial eosinophilic furunculosis or dermatophytosis associated with rupture of follicles (kerion). Biopsies should also be performed if no response to appropriate antibiotic therapy is noted.

- Response to therapy. Use proper antibiotic based on culture and susceptibility results, in the proper dosage, for the proper period of time. Evaluate response to therapy yourself (recheck).

- Treatment:

- Rule out any underlying problem.

- Gently soak and clean the affected area with antiseptic shampoos (benzoyl peroxide, chlorhexidine, ethyl lactate).

- Systemic antibiotics is often needed. Choose the antibiotic based on the culture and susceptibility results. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy. Deep bacterial infections should be treated until complete resolution of all skin lesions. Select the “first choice drugs” whenever possible. They include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid.

- Topical ointments containing a glucocorticoid and an antibiotic (e.g. ophthalmic or otic products) can be used in milder and localized cases as adjunctive therapy or alternative to systemic antibiotic therapy.

- Photobiomodulation using fluorescent light energy (e.g. Phovia™; Vetoquinol) has been shown to resolve deep pyoderma when applied as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic or as sole therapy (refer to “General information related to the management of pyoderma” below for details).

- Differential diagnoses:

-

-

- Deep Pyoderma – Interdigitial Pyoderma

- Interdigital deep pyoderma can occur at any age, sex, or breed but it is more common in short-coated dogs (e.g. English and French bulldogs, Staffordshire bull terriers, mastiff-types).

- Many cases of interdigital pyoderma result from abnormal weight bearing on one or more paws as a result of musculoskeletal problems (e.g. osteoarthritis, cruciate ligament disease etc) or excessive body weight. These predisposing factors lead to the formation of numerous comedones in between the pawpads. A thick whitish, cheesy material extrudes from the comedonic follicles when pressure is applied (this is kerato-sebaceous material!). These hair follicles with comedones will become quite dilated. Papules, nodules, hemorrhagic bullae and draining tracts will develop when these follicles become inflamed and eventually rupture. Those cases typically respond only partially to antibiotic therapy because fragments of hair shafts present in the dermis after the follicules rupture will trigger perpetuation of the inflammatory process.

- Clinical signs:

- Inflamed papules, nodules, and hemorrhagic bullae interdigitally. With time, draining tracts are formed due to rupture of the hair follicle and discharge of a sanguineo-purulent exudate (suppurative folliculitis or furunculosis present). Papules and nodules may erode or ulcerate.

- The paws may become swollen in chronic and severe cases. One or more paws may be involved.

- Pain is often present and is manifested by paw licking and limping in severe cases.

- Deep Pyoderma – Interdigitial Pyoderma

-

-

-

-

- Differential diagnoses:

- Parasitic: follicular demodicosis, pelodera, hookworm.

- Fungal: mycetoma, blastomycosis (primary cutaneous inoculation).

- Foreign body, local injury and neoplasia: typically one paw affected.

- Sterile pyogranulomas.

- Diagnosis:

- History and clinical signs.

- Skin scrapings to rule out follicular demodicosis, and rule in pelodera or hookworm.

- Cytology of exudate from draining tracts and/or ulcers and exudate underneath a crust (a few cocci, degenerated neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, +/- eosinophils).

- Fungal culture if highly suspicious of mycetoma or blastomycosis.

- Skin biopsy to rule out mycetoma, blastomycosis, sterile pyogranulomas, neoplasia, foreign body (perform if no response to antibiotic therapy).

- Response to therapy. Use a proper antibiotic, in the proper dosage, for the proper period of time. Evaluate response to therapy yourself (recheck).

- Treatment:

- Systemic antibiotic until complete resolution of clinical signs. Choose an appropriate antibiotic based on culture and susceptibility results. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy. Deep bacterial infections should be treated until complete resolution of all skin lesions. Select the “first choice drugs” whenever possible. They include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid. Lesions may only improve partially in cases associated with abnormal paw weight-bearing due to excessive body weight or musculoskeletal problems (see above). These cases may need surgical treatment.

- Topical mupirocin cream or ointment can be tried as sole therapy or in conjunction with systemic antibiotic. However, save it for cases of methicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections.

- Antiseptic soaks once to twice daily (e.g. chlorhexidine, povidone iodine) will help remove the exudate and crusts but will have minimal to no effect in treating the deep infection.

- Photobiomodulation using fluorescent light energy (e.g. Phovia™; Vetoquinol) has been shown to resolve deep pyoderma when applied as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic or as sole therapy (refer to “General information related to the management of pyoderma” below for details).

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation has been described as a promising treatment option for cases that do not respond to proper antibiotic therapy or that relapse frequently.

- Surgical fusion podoplasty can be considered when all other treatment options fail.

- When surgery cannot be performed, consider a course of oral glucocorticoid (e.g. prednisolone) after the infection is resolved to reduce the inflammation caused by fragments of hair shaft in the dermis acting as foreign material.

- It is crucial to identify and address the predisposing factors (e.g. excessive body weight, musculoskeletal problems) to decrease the changes for recurrences.

- Differential diagnoses:

-

-

- Deep Pyoderma – Generalized Deep Pyoderma

- Generalized deep pyoderma may occur in any age or sex. However, German shepherd dogs are predisposed.

- Clinical signs:

- Inflamed papules and nodules, hemorrhagic bullae, and hemorrhagic crusts develop in many parts of the body. With time, papules and nodules erode or ulcerate. Infected and inflamed hair follicles eventually rupture and hair shaft fragments and bacteria lodge in the dermis and act as foreign materials. Draining tracts are then formed to attempt expelling the foreign materials. A sanguineo-purulent exudate (suppurative folliculitis or furunculosis present) is discharged through the tracts.

- Lesions can develop anywhere but, especially the trunk, lateral thighs, chest and legs.

- The condition is often painful.

- Deep Pyoderma – Generalized Deep Pyoderma

-

-

-

-

- Dogs with chronic and severe disease may develop fever, lethargy/depression and lymphadenopathy.

- Be sure to rule out any possible underlying diseases such as allergies, endocrinopathies, immunodeficiencies, parasitic diseases (i.e. demodicosis).

- Differential diagnoses:

- Generalized demodicosis associated with furunculosis.

- Deep fungal infections (e.g. sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, coccidiodomycosis) if systemic signs are present.

- Atypical bacterial infections such as, nocardiosis, actinomycotic mycetoma, mycobacteriosis, especially, if systemic signs are present.

- Diagnosis:

- Skin scrapings to rule out demodicosis.

- Cytology of exudate from draining tracts and/or ulcers and exudate underneath a crust (a few cocci bacteria, degenerated neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, +/- eosinophils).

- Bacterial culture and sensitivity tests: perform on all deep pyoderma cases.

- Fungal culture: if highly suspicious of deep fungal infection.

- Biopsies to rule out deep or subcutaneous fungal and atypical bacterial infections.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Treatment:

- Identify and treat an underlying primary disease.

- These cases will require systemic antibiotic therapy. Antibiotic selection has to be based on culture and susceptibility results. Treatment has to be continued until complete resolution of clinical signs. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy. Select the “first choice antibiotics” whenever possible. These include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid.

- Adjunctive therapy: topical antiseptic soaks, whirlpools, or shampoos containing benzoyl peroxide or chlorhexidine. Clip long hair coat for better efficacy of topical therapy.

- Treatment:

-

- Deep Pyoderma – ” Deep Hotspot” or Pyotraumatic Folliculitis/Furunculosis

-

- “Hotspot” is typically a surface form of pyoderma. However, deep lesions may uncommonly develop if the infection extends to hair follicles and the affected follicles eventually rupture. In these cases, bacteria and hair shafts will lodge in the dermis resulting in a deep infection. Severe inflammation will issue because bacteria and hair fragments will act as foreign bodies.

- “Deep hotspot” can occur in any breed.

- Clinically and at a first glance, the lesion looks like a “hotspot”; however, the affected skin feels thick and when the lesion is squeezed, draining tracts will be noticed exuding a sanguineous-purulent material. In addition, a “deep hotspot” does not solely respond to topical therapy in most cases.

- Biopsy will show severe inflammation associated with folliculitis and furunculosis.

- Rule out: true “hotspot”, deep or subcutaneous fungal and bacterial infections.

- Identify an underlying primary cause, especially pruritic diseases (e.g. allergies, scabies etc) as these lesions are self-inflicted and often caused by pruritus.

- Treatment:

- Identify and properly treat an underlying primary disease.

- Systemic antibiotic based on culture and sensitivity results will be required. Treat until complete resolution of clinical signs. Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy. Select a “first choice antibiotic” whenever possible. These include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid.

- Clip and remove matted hair.

- Topical antiseptic soaks (e.g. chlorhexidine, benzoyl peroxide, povidone iodine).

- Photobiomodulation using fluorescent light energy (e.g. Phovia™; Vetoquinol) has been shown to resolve deep pyoderma when applied as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic or as sole therapy (refer to “General information related to the management of pyoderma” below for details).

- Oral prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day for 7 to 14 days may be necessary to reduce severe inflammation if lesions do not resolve with systemic antibiotic therapy.

Important Facts

- If you are presented to a dog with nodules, hemorrhagic bullae, erosions and ulcerations and draining tracts exuding a serous-sanguineous exudate, think of deep pyoderma.

- Deep pyoderma is rarely a primary problem so, look for an underlying primary cause. Properly treating the underlying disease will reduce the changes of recurrence.

- Systemic antibiotic therapy will be required in the management of deep pyoderma. However, the addition of topical therapy may be beneficial and can help reduce the duration of therapy.

- The antibiotic to treat deep pyodermas has to be selected based on culture and susceptibility results.

- Treat deep pyodermas until complete resolution of clinical signs.

- Recheck the patient before discontinuing therapy.

- Select a “first choice antibiotic” whenever possible. These include clindamycin, cefalexin, cefadroxil and amoxicillin clavulanic acid.

- General information related to the management of pyodermas

- Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pyoderma have recently been revised and can be freely accessed at www.iscaid.org. The reference is also available below.

- Recommendations are based on three categories of antimicrobial prescribing:

- First choice antibiotics:

- Antibiotics in this category include first generation cephalosporins (cefalexin, cefadroxil), clindamycin (culture to make sure the bacterial strain is also susceptible to erythromycin, otherwise, induced resistance may develop during treatment), and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

- Antibiotic selection based on culture and susceptibility is always preferred. However, empirical selection can be considered in (i) uncomplicated and non-recurrent cases, (ii) no history of exposure to multiple courses of antibiotic, (iii) no history of methicillin and multi-drug resistant infections and (iv) risk factors for the likelihood of antibiotic resistance are not present.

- Where compliance is an issue or gastrointestinal upset is uncontrollable, cefpodoxime and cefovecin (third generation cephalosporins) can be considered; however, their selection has to be based on culture and susceptibility test results.

- Second choice antibiotics:

- Antibiotics in this category include cefovecin, cefpodoxime, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and potentiated sulfonamides.

- Antibiotic selection has to be based on culture and susceptibility test results. The antibiotics in this category can NOT be used empirically.

- Prescribed when there is culture-based evidence that first choice drugs will not be effective, and topical antimicrobial therapy is not feasible or effective as sole therapy.

- Reserved antibiotics:

- Antibiotics in this category include rifampin, amikacin, gentamicin, and chloramphenicol.

- Antibiotic selection has to be based on culture and susceptibility test results.

- Only prescribe an antibiotic in this category if first and second choice drugs are not suitable and topical antimicrobial therapy is not feasible or effective as sole therapy.

- All drugs in this category have greater potential for adverse side effects and increased monitoring will be needed.

- Culture and susceptibility:

- Ideally, bacterial culture and susceptibility testing should be performed in all cases of bacterial skin infections. Circumstances where they are required include (i) recurrent superficial pyoderma, (ii) history of previous antibiotic therapy, (iii) new lesions developing during treatment, (iv) deep pyoderma, (v) when cytology reveals rod-shaped bacteria, (vi) any time there has been poor response to empirical therapy and (vii) in cases of methicillin-resistant staphylococcal or multi-drug resistant infections.

- Use mini-tip culturette (e.g. Marion Scientific, Kansas City, Mo) to avoid touching the skin around the lesions. Ideally, a swab that comes in a container with transport medium should be used.

- If lesions are deep, clean their surfaces with 70% alcohol, let the areas dry and, thereafter, pinch the skin to bring fresh exudate to the surface for sampling.

- Ideally, a tissue culture should be performed in cases of deep pyoderma. After cleaning the skin surface, take a 2mm sterile punch biopsy sample of the affected tissue. Thereafter, remove the epidermis with a sterile scalpel blade and place the tissue in a vial with just enough sterile saline to cover the sample.

- Empirical therapy (culture and susceptibility is not performed to select the antibiotic):

- Empirical selection can be considered in cases of first episode of infection and no history of antibiotic therapy.

- Remember!!! Staphylococcus spp produce B-lactamase. Therefore, DO NOT use: penicillin, ampicillin and amoxicillin to treat staphylococcal skin infections because most Staphylococcus strains are resistant to these antibiotics. In addition, most bacterial strains will be resistant to tetracycline and streptomycin, so avoid these drugs to treat staphylococcal infections.

- Select “first choice antibiotics” when treating empirically. They include cefalexin, cefadroxil, clindamycin and amoxicillin clavulanic acid.

- Factors to consider when choosing an antibiotic:

- Antibiotic spectrum of action – it is the most important factor to consider when selecting an antibiotic (consider the categories above)

- Potential side effects.

- Route and frequency of administration

- Client compliance.

- Cost

- Systemic antibiotics according to tiers

- First choice antibiotics

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (Clavamox®; Zoetis):

- 13.75 mg/kg PO q 12 h to q 8 h.

- Bacteriocidal.

- Higher doses (15-20 mg/kg q 12 h) may be necessary to achieve efficacy.

- First generation cephalosporins (cephalexin, [Keflex®; Flynn Pharma], cefadroxil, [Cefa-Drops®; Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc]):

- 22-33 mg/kg PO q 12 h to q 8 h.

- Bacteriocidal.

- Erythromycin: 11-17.6 mg/kg PO every (q) 8 hours:

- Bacteriostatic.

- Gastrointestinal upset

- Lincomycin: 22 mg/kg PO q 12 h.

- Clindamycin: 11 mg/kg PO q 12 h.

- Bacteriostactic.

- Gastrointestinal upset less likely.

- Cross resistance with erythromycin.

- A publication reported that you can use clindamycin once daily at the dose of 11mg/kg to treat deep pyodermas, however, the authors utilize and recommend twice daily therapy.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (Clavamox®; Zoetis):

- Second choice antibiotics

- Cefpodoxime proxetil (third generation cephalosporin): 5 – 10 mg/kg PO once daily.

- Bacteriocidal.

- Cefovecin sodium (third generation cephalosporin): 8mg/kg subcutaneously every two weeks.

- Bactericidal.

- Doxycycline: 5 mg/kg PO q 12 h.

- Bacteriostatic.

- Doxycycline is becoming more difficult to obtain. Compounded options are available, but can be more costly.

- GI upset (giving with food may decrease these effects); increased liver enzymes.

- Milk or dairy products do not seem to significantly alter the amount of drug absorbed.

- Bone and teeth abnormalities less likely, but still best to avoid in pregnant and young animals.

- May induce photosensitivity.

- If using tablets in cats, be sure to follow with at least 6 mls of water (due to risk of esophageal strictures).

- Minocycline: 5-10 mg/kg PO q 12 h.

- Best given on an empty stomach.

- Well tolerated; minimal GI upset. Rarely increased liver enzymes.

- If using capsular form, follow with 6-12ml’s of water to ensure medication is swallowed.

- Bone and teeth abnormalities less likely, but still best to avoid in pregnant and young animals.

- May induce photosensitivity.

- Enrofloxacin: 5-10 mg/kg PO once daily.

- 11 mg/kg, may be necessary for Pseudomonas spp.

- Bacteriocidal.

- Cartilage damage in young dogs (small and medium breeds up to 8 months of age, large breeds up to 12 months of age and giant breeds up to 18 months of age).

- Retinopathy leading to blindness may occur in cats at doses which exceed 5 mg/kg/day.

- Marbofloxacin: 2.75 – 5.5 mg/kg PO once daily (dogs and cats).

- Bactericidal.

- Cartilage damage in young dogs (small and medium breeds up to 8 months of age, large breeds up to 12 months of age and giant breeds up to 18 months of age).

- Ciprofloxacin:

- Given the poor oral bioavailability in dogs (33 to 40%), the authors do not recommend the use of this antibiotic.

- Even with an increased dosage, rates of absorption are nonlinear and the absorption prolonged and variable.

- Trimethoprim-sulfadimethoxine: 15.4 mg/kg to 30 mg/kg PO q 12 h

- Bacteriocidal in combination.

- Side effects include keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), polyarthritis, fever, drug eruption (type III hypersensitivity in dobermans), hypothyroidism (if used long-term).

- Ormetoprim-sulfadimethoxine: 27.5 mg/kg q 12 h -day 1, then 27.5 mg/kg PO once daily thereafter.

- Bacteriocidal in combination.

- Ataxia and aggression have been rarely observed side effects.

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), polyarthritis, fever, drug eruption (type III hypersensitivity in dobermans), hypothyroidism (if used long-term)

- Rifampin: 2.5-5 mg/kg PO q 12 h.

- Side effects include gastrointestinal upset (give with food) and hepatotoxicity.

- The owner should be advised to monitor closely for a decrease in appetite.

- Chemistry or liver profile should be performed as often as weekly to monitor for hepatoxicity.

- Owners should be advised of the potential for a reversible orange-red discoloration of the urine, tears and sclera.

- Cefpodoxime proxetil (third generation cephalosporin): 5 – 10 mg/kg PO once daily.

- Reserved antibiotics

- Chloramphenicol: 40-50 mg/kg PO q 8 h.

- Bacteriostatic.

- Be careful of human exposure (aplastic anemia).

- Gastrointestinal(GI) disturbances are common.

- Potentially bone marrow suppressive.

- Hepatotoxicity.

- Paresis especially of the hind limbs in large breed dogs may occur.

- Baseline bloodwork and monthly re-evaluation is recommended depending upon duration of therapy and patient considerations

- Aminoglycosides (e.g. amikacin and gentamicin):

- Bacteriocidal.

- Ototoxic, nephrotoxic.

- Parenteral only.

- Rarely needed.

- When needed, amikacin is used most frequently (15-30 mg/kg SC).

- Monitoring during treatment is advised as follows:

- Pre-treatment renal panel and urinalysis

- Evaluate urine sediment weekly in hourse (tubular casts degrade on their way to laboratory)

- BUN and creatinine q 2 weeks.

- If used greater than 10 to 14 days, monitor more frequently.

- Dose should be based on lean body weight since it is not lipophilic; dose older patients lower

- Rifampin: 2.5-5 mg/kg PO q 12 h.

- Side effects include gastrointestinal upset (give with food) and hepatotoxicity.

- The owner should be advised to monitor closely for a decrease in appetite.

- Chemistry or liver profile should be performed as often as weekly to monitor for hepatoxicity.

- Owners should be advised of the potential for a reversible orange-red discoloration of the urine, tears and sclera.

- Chloramphenicol: 40-50 mg/kg PO q 8 h.

- First choice antibiotics

- Topical therapy: Should always be used to treat pyodermas, as sole therapy or as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic

- The current guidelines recommend treating surface and superficial pyodermas with topical therapy. Systemic therapy can be considered in dogs with superficial pyoderma that failed to respond to topical therapy or topical therapy cannot be used due to patient or client limitations such as, an aggressive dog, owner cannot apply, facilities are not available, or the pyoderma is generalized and the dog’s hair coat is very dense.

- Clip affected areas if needed to increase treatment effectiveness.

- Whirlpools and wet soaks are very good for deep pyodermas:

- Povidone iodine solution.

- Chlorhexidine solution.

- Hypochlorous acid.

- Antibiotics:

- Mupirocin 2% ointment or cream: only use this topical antibiotic in multidrug or methicillin resistance cases to avoid resistance.

- Gentamicin, florfenicol, or orbifloxacin: these are common antibiotics in otic ointments and are typically combined with an antifungal and a steroid. These products are often used to treat localized bacterial and/or fungal skin infections or overgrowth.

- Antiseptics with residual effect:

- Hypochlorous acid (various formulations)

- Chlorhexidine 3-4% spray, mousse, wipes, or rinse

- Benzoyl peroxide gel: use carefully because it can be irritant to the skin

- Photobiomodulation using fluorescent light energy (e.g. Phovia™; Vetoquinol) has been shown to resolve superficial and deep pyoderma when applied as adjunctive therapy to systemic antibiotic or as sole therapy. The Phovia™ system uses a blue light-emitting diode length and a chromophore containing hydrogel. This system produces light in the range of 500-700 nm (i.e. green to red light). The manufacturer of Phovia™ recommends two treatments per week that is either one treatment every 3 to 4 days or two treatments back to back. After mixing the chromophore with the hydrogel, the mixture is applied to the affected area (about 2 mm thick layer). Thereafter, apply the lamp as close to the skin as possible without touching the hydrogel. The lamp has a two-minute timer. If treating back to back, remove the hydrogel after the first treatment and re-apply it before the next treatment. Read carefully the manufacturer’s instructions before use.

- Antiseptic shampoos:

- Chlorhexidine 3-4%: antibacterial, antifungal, non-staining.

- Benzoyl peroxide 2.5-3%: antibacterial, anti-seborrheic (keratolytic, degreasing), may bleach fabrics, drying.

- Ethyl lactate: antibacterial, antiseborrheic, non-drying.

- Triclosan: antibacterial.

- Sulfur, salicylic acid: antibacterial, antifungal, antiseborrheic, antipruritic. Remember! A medicated shampoo will only be effective if it is massaged on the skin for at least 10 minutes. It is also very important to rinse the shampoo off very well. The frequency of bathing varies with each case. Daily baths may be initially indicated for severe cases

- Duration of therapy:

- Surface and superficial pyoderma: If using systemic antibiotics treat until complete resolution of lesions. The previous recommendation to treat for one week past clinical resolution is not recommended by the current guidelines.

- Deep pyoderma: Treat until complete resolution of lesions. The previous recommendation to treat for two weeks past clinical resolution is not recommended by the current guidelines.

- The veterinarian is the individual responsible to determine when the antibiotic is to be discontinued. Recheck the patient as many times as you judge necessary!

- Inadequate therapy duration is a common reason for pyodermas to fail to respond to treatment

- Immune modulation:

- Remember! Immunomodulatory therapy will not cure an existent bacterial infection. You must treat the infection concurrently.

- Be sure to control an underlying disease (e.g. allergic or endocrine disorders) prior to resorting to using immunomodulators.

- Bacterins: contain various cellular products of Staphylococcus or other bacteria. Use commercially available bacterins or make autogenous bacterins.

- The immune modulation mechanism is not understood.

- Use in cases that respond to proper antibiotic therapy but relapses occur shortly after therapy is discontinued. They may help increase the interval between recurrences.

- Bacterins are not effective in treating an infection; therefore, treat the infection properly and after the infection is completely resolved, the bacterin can be used alone on a long-term basis.

- Examples of commercial bacterins:

- Staphage Lysate® (Delmont Laboratories, Swarthmore, PA):

- 0.5 mL subcutaneously twice weekly. Because the product is packaged in 10 ml vials, at least 2 vials (20 weeks) should be used to determine any efficacy.

- Helps up to 77% of recurrent cases of pyodermas. Improvement is determined by a decrease in either frequency or severity of infection. If efficacy is noticed, lifelong therapy is needed; however, the maintenance dose can be tentatively reduced to the minimum necessary to control the condition.

- ImmunoRegulin® (Neogen Corporation; Lexington, KY):

- Propionibacterium acnes.

- Recurrent pyodermas: a study reported 80% improvement (complete remission 53%) with antibiotic and ImmunoRegulin® versus 38% improvement (complete remission 30%) with antibiotic and placebo over 12 week period.

- Dose:

<7 kg:0.25 ml

7 to 20 kg:0.50 ml

1 to 34 kg:1.00 ml

34 kg: 2.00 ml

Intravenous administration twice weekly for 2 weeks, then once weekly for 10 weeks.

- Staphage Lysate® (Delmont Laboratories, Swarthmore, PA):

- First choice antibiotics:

Important Facts

- Coagulase– positive Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is the most common infective agent in canine pyodermas.

- Other agents include Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus coagulans, and Staphylococcus schleiferi .

- Remember Staphylococcus organisms produce B-lactamase, which will limit the antibiotic options to manage pyodermas. Do not use empirically penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, streptomycin and tetracycline.

- Proteus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Escherichia coli may be found as secondary invaders in deep pyoderma cases.

- Pyoderma only occurs after the cutaneous defense mechanisms are disrupted and should always be considered secondary to an underlying primary cause. Therefore, discuss with the pet owner on the first visit the importance of looking for an underlying primary cause to reduce the risks for recurrences.

- Allergic diseases are the major underlying primary cause in most cases of pyoderma.

- Endocrinopathies are probably the second most common category of underlying primary problems.

- Pyodermas usually recur. Any plan for controlling the pyoderma without serious consideration of the predisposing disease will fail.

- Current guidelines recommend treating surface and superficial pyodermas solely with topical therapy. However, systemic therapy can be considered in dogs with superficial pyoderma that failed to respond to topical therapy or topical therapy cannot be used due to patient or client limitations.

- Deep pyoderma will require the use of systemic antibiotic, which should be selected based in culture and susceptibility.

- Ideally, perform culture and sensitivity in all pyoderma cases needing systemic antibiotic.

- Circumstances where bacteria culture and susceptibility are required include (i) recurrent superficial pyodermas, (ii) new lesions developing during treatment, (iii) presence of deep pyoderma, (iv) poor response to empirical therapy, (v) cytology reveals rod-shaped bacteria, and (vi) presence of MRSP and MDR infections.

- If systemic antibiotic therapy is required, topical treatment with shampoos and various formulations (e.g. wipes, mousses, sprays) containing antiseptics (e.g. chlorhexidine, hypochlorous acid, organic acids etc), should be used in conjunction with oral antibiotic in all cases.

- Current guidelines recommend treating surface, superficial and deep pyoderma until resolution of all active lesions, in contrast to previous recommendation of treating beyond resolution of clinical signs.

References

Duclos DD, Hargis AM, Hanley PW. Pathogenesis of canine interdigital palmar and plantar comedones and follicular cysts, and their response to laser surgery. Vet Dermatol 2008; 19(3):134-41.

Hillier A, Lloyd DH, Weese JS et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (Anitmicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Cmpanion Animal Infectious Diseases). Vet Dermatol 2014; 25(3): 163-75.

Ihrke PJ. Bacterial Skin Disease in the Dog. A Guide to Canine Pyoderma. Trenton: Veterinary Learning Systems, 1996.

Kwochka KW. Recurrent Pyoderma. In: Griffin CE, Kwochka KW, MacDonald JM eds. Current Veterinary Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book,1993; 3-21.

Lundberg AT, Hathcock T, Kennis RA, et al. In vitro evaluation of bactericidal effects of fluorescent light energy on Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and S. aureus. Vet Dermatol 2024; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13235.

Marchegiani A, Spaterna A, Cerquetella M. Current application and future of fluorescent light energy biomodulation in veterinary medicine. Vet Sci 2021; 8:20.

Marchegiani A, Fruganti A, Spaterna A, et al. The effectiveness of fluorescent light energy as adjunctive therapy in canine deep pyoderma: a randomized clinical trial. Vet Med Int 2021; 6643416.

Marchegiani A, Fruganti A, Bazzano M, et al. Fluorescent light energy in the management of multidrug resistant canine pyoderma: a prospective exploratory study. Pathogens 2022; 11: 1197.

Marchegiani A, Spaterna A, Cerquetella M, et al. Fluorescence biomodulation in the management of canine interdigital pyoderma cases: a prospective, single-blinded, randomized and controlled clinical study. Vet Dermatol 2019; 30: 371-e109.

Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Small Animal Dermatology, 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2013; 418-419.

Scott DW, Miller WH, Griffin CE: Small Animal Dermatology. 5th edn. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1995279-310; 883-887.

-

-