2.1 Atopic Dermatitis – Dogs

Learning Objectives

- How is atopic dermatitis diagnosed?

- Describe the historical and clinical features of canine atopic dermatitis.

- Describe the principle, advantages and disadvantages of the different ways allergy testing can be performed.

- How do you manage atopic dermatitis with medical therapy?

- What are the principles and procedure of allergen-specific immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis?

-

General Considerations

- In 2006, the American College of Veterinary Dermatology Task Force on canine atopic dermatitis revised the definition of canine atopic dermatitis as follows: “A genetically predisposed inflammatory and pruritic allergic skin disease with characteristic clinical features associated with IgE antibodies most commonly directed against environmental allergens. This definition accounts for the fact that other allergens such as, food, can trigger or worsen the clinical signs of atopic dermatitis.

- Atopy and atopic dermatitis are often used interchangeably in animals. However, because dogs do not frequently develop concurrent upper respiratory signs or asthma like their human counterparts, atopic dermatitis is a more appropriate disease name for dogs.

- Atopic dermatitis is a common allergic skin disease of dogs and is frequently seen in small or mixed animal practices.

- Reported incidence are:

- 15% of canine population.

- 3 – 8% of skin disorders at a university practice.

- 30% of skin disorders at a private specialty practice.

- The ACVD Task Force on atopic dermatitis also defined the subset of dogs with clinical signs identical to the ones with atopic dermatitis sensus stricto but that have negative skin and serum allergen-specific IgE tests. These dogs have been referred as atopic-like and the definition of cases that fall within this category is as follows: “Atopic-like dermatitis is an inflammatory and pruritic skin disease with clinical features identical to those seen in canine atopic dermatitis in which an IgE response to environmental or other allergens cannot be documented”.

-

Etiology and Pathogenesis

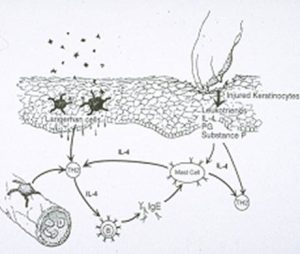

- The pathogenesis of canine atopic dermatitis is complex and new concepts are still emerging.

- Studies have demonstrated an abnormal skin barrier in patients with atopic dermatitis facilitating environmental allergen penetration and sensitization. Studies have also shown that the skin of dogs with atopic dermatitis has a predominance of Th2 lymphocytes, especially in the acute phase of the disease. Th2 lymphocytes favor an allergic status. It is not known, however, if the skin barrier is primarily defective or if an allergic inflammation comes first and causes a defective skin barrier subsequently. We cannot answer this question with certainty at this time; however, we can say that both, a skin barrier defect and an immunologic dysfunction, play a role. It is important to know that environmental and genetic factors also participate in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis.

- The route of allergen exposure and sensitization can be oral, respiratory, and percutaneous/epicutaneous; however, the percutaneous/epicutaneous route appears to be most important.

- Proposed mechanism of T lymphocyte sensitization:

- Allergens enter the body by inhalation, ingestion, or percutaneous/epicutaneous absorption

- Allergens are taken up by antigen presenting cells such as, Langerhans cells, which bring the antigen to the regional lymph node.

- After being processed by Langerhans cells, the allergens are presented to naïve T lymphocytes, which are activated to release IL-4 and IL-13, among other cytokines.

- IL-4 stimulates B cells to release allergen-specific IgE immunoglobulins.

- The activated allergen-specific T lymphocytes clonally expand and these cells home to the skin.

- After the sensitization phase, the process of antigen presentation and activation of allergen-specific T lymphocytes is much faster and effective.

- These activated T lymphocytes release many cytokines

- IL-31, which induces pruritus.

- L-5, which recruits eosinophils.

- And many others to cause skin thickening, inflammation, and disruption of the skin barrier.

Important Facts

- Canine atopic dermatitis is a common inflammatory and pruritic skin disease associated with high levels of IgE antibodies against common environmental allergens.

- The pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis is complex and not yet completely understood.

- Increasing evidence support the participation of skin barrier defect, immunologic dysfunction, environmental and genetic factors in the pathogenesis of canine atopic dermatitis.

- Allergen sensitization can occur via oral, respiratory, and percutaneous/epicutaneous routes; however, the percutaneous/epicutaneous route appears to be most important.

-

Allergens Involved in Canine Atopic Dermatitis

- Pollens (glycoprotein antigens):

- Somewhat regional.

- Season varies with the pollen; trees pollinate first, then grasses and weeds.

- House Dust Mites:

- Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae are the most common dust mites in many parts of the world.

- Mostly nonseasonal allergens

- House Dust:

- Complex substances consisting of breakdown products from clothing, furniture, animal and human dander, molds, insect parts, and house dust mites.

- Mostly nonseasonal allergens.

- Molds:

- Found in all areas of the U.S. in soil and decaying organic matter, damp basements, etc.

- Peak in U.S. depends on weather, but usually is in June through September. Some indoor molds can be present year-round.

- Epidermal Antigens (cat, horse, etc) – less common allergens:

- Hair is not a major antigen; rather, it is the dander (desquamated epidermal cells) and dried saliva that has high concentrations of substances to which allergy develops. Animals do not appear to be often allergic to other animals or to humans.

- Feathers (pillows, birds).

- Wool.

- Miscellaneous – less common:

- Household insects.

- Furniture stuffing.

- Tobacco

- Pollens (glycoprotein antigens):

Important Facts

- Allergens commonly involved in canine atopic dermatitis are pollens and house dust mites.

-

History Findings in Atopic Dermatitis

- A detailed history is the single most important factor in the diagnosis and management of a patient with atopic dermatitis.

- Important History Facts:

- The hallmark clinical sign of canine atopic dermatitis is pruritus. It is the initial sign noticed by the pet owner, as skin inflammation is typically subtle at the beginning. When investigating the presence of pruritus or itch, ask the owner if the dog scratches, bites/nibbles at the skin, licks and rubs the body as any of these signs can be a response to pruritus.

- The disease usually starts at 1 to 3 years of age, but onset can be from 6 months to 6 years of age. After 3 years of age the incidence of atopic dermatitis decreases and it occurs infrequently in dogs older than 6 years of age.

- Clinical signs can be seasonal or nonseasonal. Many initially seasonal cases progress to a year-round condition after 3 to 4 years. A dog allergic to year-round and seasonal allergens will have a history of clinical signs present throughout the year but that exacerbate during one or more season.

- In general, the pruritus and skin inflammation associated with atopic dermatitis respond well to corticosteroid therapy.

- Breed Predisposition:

- Atopic dermatitis can occur in any breed but because of the genetic predisposition, the disorder is recognized more frequently in certain breeds or families. Breed predilection varies according to the geographic region.

- Examples of breeds with reported high incidence of atopic dermatitis include Boston Terrier, Cairn Terrier, English Bulldog, Miniature Schnauzer, Pug, Wirehaired Fox Terrier, West Highland White Terrier, Golden and Labrador Retrievers, Lhasa Apso, Dalmatian, Irish and English Setter.

Important Facts

- A thorough history is the single most important factor in the diagnosis and treatment of canine atopic dermatitis.

- The hallmark clinical sign of canine atopic dermatitis is pruritus responsive to corticosteroid therapy.

- Signs typically start at 1 to 3 years of age, but onset can occur in dogs as young as 6 months or as old as 6 years of age.

- Clinical signs can be seasonal or nonseasonal and correlate with the allergens that the dog becomes allergic to.

- Because of the genetic predisposition, the disorder is recognized more frequently in certain breeds or families.

-

Physical Examination Findings in Atopic Dermatitis

- As mentioned before, dogs with atopic dermatitis are pruritic and pruritus is typically the first sign observed by the owner. Many of the findings during thorough physical examination of the skin will be related to the severity of pruritus, presence of secondary infections and disease duration.

- The disease distribution correlates to where the dog itches.

- Face (periocular and perioral pruritus).

- Feet licking and chewing.

- Axilla, ventrum, lateral thorax, flanks.

- Caudal aspects of the carpal joints, cranial aspects of the elbows (i.e. flexor cubital) and flexural surfaces of the tarsi.

- Chronic pruritic otitis with inflamed pinnae (often recurrent).

-

-

-

- Perianal pruritus occurs relatively often and can be mistaken by anal sacculitis.

-

-

-

- What lesions do we see?

- Diffuse erythema that can be mild or severe depending on disease severity and duration. As the disease progresses, primary and secondary lesions occur as a result of secondary disorders (such as bacterial skin infection or overgrowth, seborrhea, Malassezia overgrowth causing dermatitis) and chronic trauma from itching.

- Secondary lesions:

- The photos below show moderate to severe erythema due to Malassezia and/or bacterial overgrowth and self-inflicted alopecia due to chronic pruritus in three dogs with different stages of atopic dermatitis.

- What lesions do we see?

-

-

-

- Excoriations and self-inflicted alopecia are common signs in dogs with chronic pruritus.

-

-

-

-

-

- Hyperpigmentation and lichenification are classical signs of chronic inflammation.

-

-

-

-

- Secondary superficial pyoderma is VERY common in canine atopic dermatitis.

- Papules, pustules, yellowish crusts, epidermal collarettes, and moth-eaten-alopecia are all signs of superficial pyoderma.

- Secondary superficial pyoderma is VERY common in canine atopic dermatitis.

-

a dog with superficial pyoderma secondary to atopic dermatitis

-

-

-

- Some predisposing factors for the development of secondary superficial pyoderma in dogs with atopic dermatitis include:

- Keratinocytes of atopic dogs have shown to bind Staphylococcus organisms more easily.

- In dogs with atopic dermatitis, the stratum corneum is deficient in ceramides, which is an important lipid component of the intercellular lipid lamellae. This results in a skin barrier defect.

- Other components of the skin barrier can be altered in dogs with atopic dermatitis because of inflammation, changes in the microenvironment, and self-trauma from pruritus. Some of these components include the skin pH and microbiota.

- Some predisposing factors for the development of secondary superficial pyoderma in dogs with atopic dermatitis include:

- Secondary seborrhea is also commonly seen in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Excessive scaling is the hallmark sign of seborrhea. If the scales are associated with excessive sebum secretion, the patient has seborrhea oleosa. If the scales are not associated with excessive sebum secretion, the patient has seborrhea sicca.

- Seborrhea oleosa occurs more often in uncontrolled atopic dermatitis.

- Remember! Excessive sebum provides a good environment for bacteria (Staphylococcus spp. and yeast (Malassezia spp.) to overgrow.

-

-

-

-

- Secondary Malassezia dermatitis due to Malassezia overgrowth is commonly seen in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Clinical signs are variable and include one or more of the following: erythema, scaling, brownish discoloration, lichenification, excessive sebum accumulation.

- Malassezia overgrowth often occurs in dogs with oily skin but it can also be associated with dry skin.

- Be suspicious of Malassezia overgrowth in the presence of lichenified skin with erythema, alopecia and scales. Perform cytology!

- Malassezia overgrowth cause inflammation, thus, it is often referred as Malassezia dermatitis and these terms are used interchangeably

- Secondary Malassezia dermatitis due to Malassezia overgrowth is commonly seen in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

-

-

-

-

- Ventral neck, axillary regions, inguinal area and interdigital spaces are sites often affected by Malassezia dermatitis.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Malassezia dermatitis is often pruritic thus, in most cases it significantly aggravates the pruritus caused by atopic dermatitis.

- One study demonstrated IgE antibodies against Malassezia spp. organisms. This finding suggests an allergic response to some Malassezia antigens, which can explain the severe pruritus present in many dogs.

- Be suspicious of secondary Malassezia dermatitis if a dog is chewing (not licking) at his feet.

- Malassezia overgrowth is often associated with Staphylococcus overgrowth because the growth factors secreted by each stimulate the growth of both.

-

-

-

ix. Otitis Externa:

-

-

-

-

-

- Otitis externa is reported in 16.8% to 55% of dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Atopic dermatitis is the most common cause of chronic otitis externa and recurrent otitis externa can rarely be the sole sign of atopic dermatitis.

- Initially, erythema may be the only sign of otitis.

- Eventually, bacteria and/or yeast infections will occur and other signs will develop.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Other Facts:

- Acute moist dermatitis (“hot spots”) can be a sign of severe pruritus in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Ocular signs can be present in some cases (conjunctivitis, lacrimation, rubbing at eyes). Conjunctivitis and rhinitis have been reported to occur in 30 to 50% of atopic dogs.

- Respiratory signs are rare in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Anal pruritus can be a sign of atopic dermatitis.

- Remember!

- Recognizing and treating secondary problems will significantly improve the animal’s allergic condition in most cases.

- Fleabite hypersensitivity can concur as often as 80% in areas of the country where fleas are a common problem.

- Food allergy is reported to occur in up to 30% of dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Other Facts:

-

-

Important Facts

- Pruritus in atopic dermatitis is typically localized to the face, axilla, ventrum, lateral thorax and feet.

- Otitis externa is very common in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Secondary staphylococcal pyoderma, secondary seborrhea and secondary Malassezia dermatitis are VERY common in atopic dogs and often aggravate the pruritus and inflammation primarily related with atopic dermatitis.

-

Differential Diagnoses and Diagnosis in Canine Atopic Dermatitis

- Differential diagnosis for pruritus without primary lesions:

- Food allergy – you cannot differentiate atopic dermatitis from food allergy based on clinical signs because food antigens can trigger signs of atopic dermatitis. For this reason, it is recommended to use the terminology “environmental-induced atopic dermatitis” or “food-induced atopic dermatitis”, when applicable.

- Differential diagnoses for pruritus with papules:

- Superficial pyoderma (secondary to atopic dermatitis and food allergy but it can be primary idiopathic in a few cases).

- Flea allergy.

- Sarcoptic mange.

- Other ectoparasitic diseases (e.g. pediculosis, cheyletiellosis).

- Contact allergy.

- Drug eruption.

- Differential diagnosis for pruritus without primary lesions:

Important Facts

- Atopic dermatitis and food allergy cannot be differentiated based on clinical signs because food allergens can trigger atopic dermatitis. Thus, food allergy should be ruled out in every dog with year-round signs compatible with atopic dermatitis.

- Other than food allergy, other pruritic dermatoses should be included in the differential diagnoses list when suspecting of atopic dermatitis. These include scabies, fleabite allergy, cheyletiellosis, contact allergy, pediculosis etc.

- The list of differential diagnoses should be prioritized according to the patient’s history and clinical signs to determine which diagnostic tests should be performed.

-

- Diagnosis:

- Currently, there is no specific test to diagnose atopic dermatitis.

- The diagnosis should be based on a compatible history, suggestive clinical signs and the exclusion of other pruritic skin disorders (such as food allergy, fleabite allergy, sarcoptic mange, cheyletiellosis). The intradermal and serum allergen tests are best used to determine the allergens that will be included in the mixture for the allergen-specific immunotherapy and a negative result should not rule atopic dermatitis. Therefore, these tests should not be used as sole diagnostic tests. However, positive results that correlate with the patient’s history will support a presumptive diagnosis of atopic dermatitis.

- A good history is extremely important!

- Signalment (breed, age of onset).

- Seasonal or non-seasonal pruritus.

- Itch before rash:

- If the client reports that the pruritus came before the skin lesions, atopic dermatitis and/or food allergy is a likely diagnosis.

- Atopic dermatitis should be responsive to anti-inflammatory doses of corticosteroids.

- Discuss with the pet owner doing a food elimination trial if clinical signs are year-round. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy can look the same. When food allergens trigger signs of atopic dermatitis, we can refer these dogs as having “food-induced atopic dermatitis”.

- Skin Biopsy:

-

- It is not typically performed because the findings are non-specific.

- Findings: superficial perivascular to interstitial lymphocytic-histiocytic dermatitis – eosinophils are usually absent or present in small numbers.

-

- Diagnosis:

Important Facts

- There is no specific diagnostic test for atopic dermatitis.

- The diagnosis of atopic dermatitis should be based on a compatible history, suggestive clinical signs and the elimination of other pruritic skin diseases.

- The main pruritic disease that needs to be ruled out when suspecting of atopic dermatitis is food allergy because food allergens will trigger signs of atopic dermatitis.

- Other causes of pruritic dermatitis that should be included in the list of differential diagnoses include scabies, fleabite allergy, cheyletiellosis, contact allergy, pediculosis and pruritic pyoderma.

- The prioritization of the list of differentials based on the patient’s history and clinical signs will determined which of these diseases should be pursued.

- The intradermal and serum allergen tests should not be used to diagnose atopic dermatitis.

- Atopic dermatitis typically responds to anti-inflammatory doses of corticosteroids.

-

Treatment

- Canine atopic dermatitis is a complex, lifelong disease with various degrees of severity, which will require treatment regimens according to each patient. Every patient is different!

- Client education is very important and should be implemented at the time the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis is established. Owners must know what to expect!

- Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease.

- It is a controllable, but not curable disease.

- Periodic relapses and secondary problems (mainly staphylococcal pyoderma and Malassezia dermatitis) are to be expected. It is important that you contact our office immediately when a disease flare occurs.

- No one treatment is universally effective and we will work as a team to determine the best treatment regimen for your pet. This may entail many office visits.

- The “Pruritic Threshold” concept in managing atopic disease:

- Every animal will tolerate a certain amount of pruritic stimulus without scratching. Once this threshold is exceeded, clinical signs result.

- Therefore, all possible contributing pruritic stimuli must be evaluated in each patient, and treated as necessary. Examples:

- Identify the secondary complications: staphylococcal pyoderma, Malassezia dermatitis, seborrhea, etc. VERY important!

- Are concurrent food allergy present?

- Is concurrent fleabite allergy dermatitis present?

- Personality of the animal may influence mode and response to treatment.

- Avoidance is possible for some allergens (examples: avoiding wool, limiting outdoor time in pollen-sensitive animals, various manipulations to keep dust mite populations down) but it is often impractical. Moreover, the evidence that avoidance significantly impacts disease severity is currently weak.

- Allergen testing: intradermal and/or serum allergen tests are discussed under treatment because the main reason to perform these tests is to formulate the allergen-specific immunotherapy.

-

-

- Intradermal Testing (IDT):

- Intradermal testing is currently the accepted “gold standard” for selecting allergens for the allergen-specific immunotherapy in animals, though this may change with the improvement in serum tests and additional studies comparing the outcome of immunotherapy based on each test.

- Drugs can interfere with the test IDT results

- Drug withdrawal prior to IDT testing:

- Antihistamines should be discontinued 7-14 days prior to testing.

- Injectable corticosteroids should be discontinued 8 to 12 weeks prior to testing depending on the strength of the steroid.

- Oral prednisone should be discontinued at least 2 weeks but prolonged use requires a 4-week withdrawal.

- Topical glucocorticoids can have a profound effect on the IDT test results and should be stopped 2 to 4 weeks depending on the strength of the steroid and duration of therapy.

- Essential fatty acids should be discontinued 7 days prior to IDT testing.

- No withdrawal time is needed for cyclosporine and Apoquel (oclacitinib) if these drugs have been given for only 30 days before the skin test.

- No withdrawal needed for Cytopoint (IL-31 monoclonal antibody).

- In vitro allergen testing:

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), liquid-phase immune-enzymatic assay and the radio-allergoabsorbent test (RAST) are used more often in veterinary medicine. These tests measure allergen-specific IgE concentrations in serum.

- Advantages:

- Little patient preparation (only requires a blood sample).

- No training.

- Useful for those dogs that cannot be skin tested.

- Fewer false negatives from exogenous drugs (though some companies recommend steroid withdrawal).

- Disadvantages:

- No standardization of allergen extracts.

- Methodology between laboratories are different

- Poor correlation with IDT test.

- High incidence of false positive reactions. However, studies have shown that the presence of antibodies against cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) is responsible for the false positive reactions to plant and insect allergens. Therefore, some laboratories have developed methods to block CCD-IgE antibodies to reduce the number of false positive reactions.

- Not reproducible.

- When should you consider IDT or in vitro testing for patients with atopic dermatitis:

-

- If pet owners are willing to try their pets on allergen-specific immunotherapy.

- After ruling out other pruritic diseases, especially food allergy and scabies.

- When medical management is unsatisfactory.

- Ideally, clinical signs have been presented for at least 1 year, which will determine if the signs are seasonal or year round. This will allow for more accurate selection of allergens to compose the allergen-specific immunotherapy.

- Pet can tolerate the allergen-specific immunotherapy administration method (i.e. subcutaneous or sublingual protocols).

-

- Intradermal Testing (IDT):

-

F. Allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT, also called hyposensitization or desensitization) and Regionally-specific immunotherapy (RESPIT):

-

-

-

- It is the only treatment that can modify the allergic response in favor of desensitization or hyposensitization. Therefore, it should be offered to all patients with atopic dermatitis, especially young dogs with year-round clinical signs.

- The mechanism of action is not well-known but may include the following:

- Induction of regulatory T lymphocytes which secrete the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGβ) reducing the inflammatory response.

- Shift from a TH2 predominant response to a TH1 response resulting in a reduced synthesis of IL-4, IL-13 and IL-5 by TH2 cells. The change in the cytokine milieu will ultimately lead to a decrease in allergen-specific IgE antibodies.

- Selection of allergens:

- In general, no more than 15-20 aqueous allergens are included in an ASIT allergen mixture. If the dog reacts to more than 15-20 allergens, prepare two or more vial sets.

- In a dog with numerous positive reactions, select those allergens that are most prevalent in the dog’s environment and that correlate with the seasonality of clinical signs.

- Molds are high in proteases and may inactivate other allergens. They should be ideally placed in separate vials. This is currently up for debate!

- Subcutaneous immunotherapy dose regimen: extracts of the offending allergens are administered in gradual-increasing amounts.

- Three sets of vials with increasing concentrations of allergen extracts (i.e. vial #1 least concentrated and vial#3 most concentrated) are administered according to a protocol that will ultimately lead to the maintenance regimen of 1 mL of the most concentrated vial (#3) administered subcutaneously every 3 weeks.

- Frequency of administration should be tailored to the patient’s response to therapy. For example: the allergen mixture can be given every 14 days instead of every 21 days if owners notice a pattern of worsening of clinical signs 2 weeks after the last injection. The volume can be reduced in animals that develop side effects such as, increase in itching, lethargy etc. Animals that develop an anaphylactic reaction should be pre-treated and closely monitored as mentioned under “adverse reactions”.

- Response rate:

- Most authors report 60 to 70% response in dogs, if response is defined by at least a 50% improvement in clinical signs. A small subset of atopic dogs become asymptomatic with immunotherapy therapy; however, it must be given lifelong until scientific evidence dictates otherwise.

- The 30 to 40% of atopic animals that do not respond to subcutaneous immunotherapy can be given the option of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT; see below) or medical therapy as the sole long-term treatment regimen (e.g. antihistamines, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, oclacitinib, monoclonal antibody against IL-31 etc.).

- In general, with aqueous extracts a response is not seen before 3 months and may not be observed until 9 to 12 months.

- If the immunotherapy helps control the atopic disease, it must be continued for life until scientific evidence dictates to the contrary.

- Additional medical therapy is often necessary to control pruritus while waiting for ASIT to work.

- Animals on immunotherapy should be followed up after 3, 6 and 12 months on therapy. If no improvement is noted after 12 months, discontinuation is recommended.

- Adverse reactions: extracts of the offending allergens are injected in gradual increases in concentration.

- Mild reactions occur in approximately 10% of the patients. They include intensification of clinical signs for a few hours, local edema or pruritus at the injection site.

- Anaphylaxis occurs in less than 1% of the dogs treated. Signs in dogs are generally depression, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, and collapse. Facial swelling and hives can also be seen.

- If signs of anaphylaxis occur, for the next and subsequent injections, pretreat with 2 mg/kg of oral diphenhydramine, one dose 1 to 2 hours prior to the injection.

- After the episode, the next few injections should be given in the veterinarian’s office (with diphenhydramine pretreatment) and the dog observed for one hour after the injection.

- If the immunotherapy mixture contains more than 15 allergens, the authors proactively recommend pretreating the pet long-term with an antihistamine 1 to 2 hours before each injection.

- Sublingual Immunotherapy (SLIT)

- The information provided above is related with administering the immunotherapy subcutaneously. SLIT involves giving the allergen extract under the tongue or more realistically in the cheek pouch. This method is an option for owners that do not feel comfortable administering injections to their pets.

- Dose: follow the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. However, the authors consistently recommend twice-daily administrations even when the manufacturer’s instruction is once daily therapy. The frequency of administration is the same during the induction and maintenance phases for the duration of therapy. This may be an inconvenience to some clients. In contrast, the maintenance protocol for allergens administrated subcutaneously is one injection every 21 days (it starts with every-other-day, then every 10 days, then every 3 weeks). In humans, it is recommended to hold the solution under the tongue for 1 minute. In dogs, the recommendation is to not allow the animal drink or eat for a short period after administration.

- Response rate: The experience with SLIT in dogs with atopic dermatitis is limited at this time. However, studies show a success rate of about 60%, which is similar to the response observed with subcutaneous therapy. In addition, anecdotal reports have indicated that response to SLIT can be noted in some dogs that did not respond to the conventional (i.e. subcutaneous) immunotherapy. Frequent follow-up visits are recommended to evaluate response to therapy (3, 6, 12 months after initiation). If no improvement is noted after 12 months, discontinuation is recommended.

- Adverse reactions: Most animals tolerate SLIT very well. Possible adverse reactions include scratching at the mouth, which tends to disappear after few treatments and occasional vomiting that also tends to resolve after a few doses. Anaphylactic reactions have not been reported in dogs.

- Intra-Lymphatic Immunotherapy (ILIT)

- ILIT has been used by some dermatologists in Europe. A study from Germany (Fisher et al 2020) compared the efficacy of the SCIT, SLIT and ILIT protocols. Interestingly, the ILIT was the most effective in reducing the pruritus and inflammation associated with atopic dermatitis in dogs. However, in this study, the authors switched to the SCIT maintenance protocol after four monthly ILIT treatments. This was done because a previous study showed that the effect of ILIT wanes shortly after treatment discontinuation.

- Protocol: The allergen mixture is combined with aluminum hydroxide and injected into the popliteal lymph node once monthly under ultrasound guidance. The injections should be given by veterinarians. For more detail regarding the treatment protocol, refer to the studies by Fisher et al 2020 and Timm et al 2018 included in the references.

- Response rate: The study by Fisher et al showed that four intralymphatic monthly doses of allergens mixed in aluminum hydroxide followed by monthly subcutaneous injections of the same allergen mixture, resulted in 60% of the atopic dogs returning to normal state. In comparison, 17% of the dogs on solely subcutaneous therapy and 14% of the dogs on sublingual therapy returned to normal state. The authors’ definition of normal included a CADESI-04 ≤12, PVAS ≤2.5 and medication score ≤10, with no systemic immunomodulatory drug being used.

- Adverse reactions: Most dogs appear to tolerate ILIT very well. Reported adverse reactions included swelling of the lymph node post-injection and increased pruritus.

- More studies are needed to determine the best protocol for ILIT, and its long-term safety and efficacy

- Regionally-specific immunotherapy (RESPIT)

- The allergenic extract mixtures in RESPIT are formulated according to the dog’s geographic location rather than the dog’s individual response to an allergen test. Therefore, it is not a patient-specific immunotherapy.

- Protocol: Follow the treatment protocol recommended by the company (https://nextmune.shop/pages/respit). The mixture is available in injectable and oral forms.

- Response rate: A retrospective study enrolling 103 dogs with atopic dermatitis, reported good or excellent response in 57% of the cases. This is similar to rates reported in studies investigating the effect of allergen-specific immunotherapy.

- Adverse reactions: RESPIT’s safety profile is anecdotally reported to be similar to that of allergen-specific immunotherapy. .

- An advantage of RESPIT over allergen-specific immunotherapy is that allergen testing is not required, which may reduce costs for pet owners. In addition, withdrawal of immunomodulatory drugs is not an issue.

-

-

G. Medical Management of Atopic Dermatitis:

-

-

-

-

-

- Antihistamines. At this time, few well-designed randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial have shown that antihistamines do not improve significantly the pruritus and/or lesions associated with canine atopic dermatitis. However, most dermatologists still use antihistamines in patients with atopic dermatitis primarily for their sedative effect. It has been reported to be useful in 10 to 20% of the cases.

- Antihistamines should be used with caution in dogs with a history of seizures.

- Perform a trial using several antihistamines and ask the owner to determine which one worked the best, if any. Try each one for 7 to 14 days.

- Hydroxyzine: 2.2 mg/kg every 8 to 12 hours.

- Diphenhydramine: 2.2 mg/kg 8 to 12 hours.

- Chlorpheniramine 0.5 to 2 mg/kg every 12 hours.

- Amitriptyline: 2.2 mg/kg every 12 hours – may cause arrhythmias – check heart first.

- Clemastine: The bioavailability of this antihistamine in dogs is very poor. AVOID IT!

- Be sure to eliminate any secondary problem (e.g. pyoderma, Malassezia dermatitis) before starting an antihistamine trial:

- The beneficial effect of antihistamines is reduced or eliminated when secondary problems are present.

- Do not start an antihistamine trial and treat a secondary pyoderma concurrently. Any beneficial effect observed could be a result of the resolution of the pyoderma and not the antihistamine treatment.

- Do not start an antihistamine trial if a dog’s pruritus level is moderate to severe because owners most likely will not perceive a response. Reduce the pruritus level first by treating any secondary infections and/or administering anti-pruritic/anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Essential fatty acids:

- Very few well-designed clinical trials standardizing the diets before trial initiation and supplementing the dogs for an adequate period of time have been conducted to support the use of essential fatty acids to manage dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- The few studies have shown that essential fatty acids may allow for a reduction of steroid dosage by 30% or more.

- Omega-3 fatty acids including eicosapentanoic acid (EPA), docosapentanoic acid, and docosahexanoic acid (DHA) inhibit production of the pro-inflammatory mediators prostaglandins 2 (PG2) series and leukotrienes 4 (LT4) series.

- The ideal dose and ratio of omega-6:omega-3 fatty acids to be used is currently unknown. Dose of EPA and DHA in one study was 180 mg and 120 mg /10 lbs. of body weight, respectively. This dose accounts for 66 mg/kg per day of combined EPA and DHA, However, doses as high as 100-150 mg/kg/day of combined EPA and DHA may be more beneficial. Make sure to select the product from a reputable company. Diarrhea may occur when doses are high.

- It may take up to 2-3 months before any result can be seen. Therefore, try essential fatty acids for at least 3 months before evaluating their benefit.

- Fatty acids may work synergistically with antihistamines and allow for a dose reduction of glucocorticoids or other immunomodulatory drugs.

- Glucocorticoids:

- Inhibits inflammation and pruritus very effectively.

- Good efficacy for most atopic dogs, but many will eventually develop undesirable adverse effects.

- Glucocorticoid may be an appropriate therapy if the animal has signs of atopic dermatitis for only a few months and if the pet owner can tolerate the side effects!

- The drug of choice is a short-acting glucocorticoid such as prednisone, prednisolone or methylprednisolone, which should be administered on an alternate-day therapy if given long-term. Avoid the use of more potent drugs.

- Starting dose is 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg/day of prednisone or prednisolone and 0.4 to 0.8 mg of methylprednisolone PO, daily until remission then 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg every-other-day as maintenance therapy if used long-term.

- Avoid injectable glucocorticoids to treat cutaneous allergic diseases in the dog. Dogs are very susceptible to the side effects of systemic glucocorticoids and many injectable forms have a potent and long-lasting effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Moreover, their anti-pruritic effect only last about 7 to 14 days. Therefore, use only oral glucocorticoids to manage canine allergies (ideally the short-acting ones such as, prednisolone, prednisone or methylprednisolone).

- Glucocorticoids can be combined with antihistamines and/or fatty acid supplements; this may decrease the required dose of oral glucocorticoids.

- Before considering the use of glucocorticoids to manage dogs with atopic dermatitis, treat any staphylococcal infection and Malassezia and/or Staphylococcus overgrowth, if they are present. These secondary problems usually aggravate the pruritus and inflammation primarily caused by atopic dermatitis. Glucocorticoid therapy may be unnecessary or needed at a lower dosage if you successfully resolve the infection/overgrowth.

- Perform chemistry profile, urinalysis and urine culture at least once a year if corticosteroids will be used as maintenance therapy to monitor for potential side effects.

- Other immunomodulating options:

- Cyclosporine (Atopica®, Cyclavance® – microemulsion formulations):

- Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor that suppresses T-cell activation and proliferation by preventing the transcription of genes responsible for interleukin-2 production. This will ultimately result in the inhibition of various cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. No difference in treatment efficacy was noted between prednisolone and cyclosporine in one study. Cost can be a limiting factor.

- Dose: 5mg/kg q 24h, orally, given at least 2 hours apart from feeding. The bioavailability of cyclosporine in dogs is quite variable but is typically only about 45% and food may reduce it to 25%.

- Cyclosporine can be given in combination with ketoconazole to reduce treatment cost. Ketoconazole inhibits liver cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of cyclosporine resulting in its increased blood and skin concentrations. It also inhibits P-glycoprotein in the gastrointestinal tract allowing for higher absorption of cyclosporine. Therefore, if given in combination with ketoconazole at 2.5 or 5 mg/kg/day, the dose of cyclosporine should be reduced in half (i.e. 2.5 mg/kg q 24h). It is important to remember that ketoconazole, in contrast to cyclosporine, should be ideally given with food. Prescribing this combination can be tricky to owners!

- A study looked at the accuracy and precision of compounded cyclosporine capsules and solutions and found that the compounded cyclosporine solution may deviate by more than 10% from the labelled strength. The authors recommend that compounded cyclosporine should only be prescribed when the commercial product cannot be used since the bioavailability and clinical efficacy of compounded cyclosporine is currently unknown.

- Perform a 4-6-week treatment trial before evaluating response to therapy as it can take this long for an effect to be noticed. Prednisolone or oclacitinib can be used to control the pruritus and inflammation during the 4-6 weeks cyclosporine lag time.

- Side effects: Reported side effects associated with cyclosporine administration in dogs include vomiting (most common), diarrhea, gingival hyperplasia, hypertrichosis and papillomatosis. Given frozen and before bedtime may help reduce vomiting episodes.

- For monitoring, perform urinalysis, urine culture and chemistry profile once a year if the dog will be maintained on long-term cyclosporine therapy.

- Oclacitinib maleate (Apoquel®):

- Oclacitinib is a selective inhibitor of primarily Janus kinase (JAK) 1 enzyme, a signal transducer important in the signaling of cytokines involved in inflammation and pruritus. It is approved by FDA for the control of canine allergic dermatitis and, specifically, atopic dermatitis. It is labeled for dogs at least 12 months of age.

- Two large blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed that Apoquel® significantly reduced skin lesions and pruritus in dogs with atopic dermatitis and allergic dermatitis compared to dogs treated with placebo. Improvement in pruritus was noticed in most dogs during the first day of treatment.

- Studies have also shown that the efficacy of oclacitinib in treating canine atopic dermatitis is comparable to that of prednisolone and cyclosporine.

- More than 80% of dogs have shown to benefit from this treatment modality.

- Dose: 0.4 to 0.6 mg/kg orally, q 12h for up to 2 weeks, then once daily as maintenance. Because the half-life of Apoquel® is short (about 4 to 6 hours), dividing the daily dose into two administrations, 12 hours apart, may be more beneficial than giving it once daily. However, avoid using 0.4 to 0.6 mg/kg q 12h long-term because JAK2 enzyme may be also inhibited, which can result in reduced hematopoiesis. Apoquel® can be administered with or without food. The film-coated and flavored chewable tablet strengths include 3.6 mg, 5.4 mg and 16 mg.

- Side effects: The most frequent side effects, which occurred uncommonly in the field trials, include vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia and lethargy. These side effects resolved with discontinuation of the drug. Other side effects included decreased leukocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes) counts, serum globulin, and increased cholesterol and lipase compared to the placebo group.

- Bloodwork (CBC and chemistry panel) is recommended prior to starting therapy, after 2-3 months of therapy, and yearly if therapy is ongoing.

- Ilunocitinib (Zenrelia®) :

- Ilunocitinib is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor. It is approved for use in dogs of at least 12 months to control the pruritus associated with allergic dermatitis and to control the pruritus and skin lesions associated with atopic dermatitis.

- Randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled field trials including dogs with atopic dermatitis (268 dogs) and allergic dermatitis (306 dogs) showed that significantly more dogs treated with ilunocitinib had at least 50% decrease in pruritus scores (PVAS) from baseline and at least 50% reduction in skin lesions scores (CADESI -4) from baseline compared to dogs treated with placebo.

- Another study compared the effects of ilunocitinib (Zenrelia®) and oclacitinib (Apoquel®) for the control of pruritus and skin lesions in dogs with atopic dermatitis. In this study, subjective measurement of overall response was significantly better for ilunocitinib after 14 days, which corresponds to the time that the dose of oclacitinib is reduced to half per label recommendation. In contrast, the recommended starting dose of ilunocitinib is maintained throughout the treatment period.

- Dose: The ilunocitinib dosage ranges from 0.6 to 0.8 mg/kg (0.27 to 0.36/lb) administered orally, once daily, with or without food. Table sizes include 4.8 mg, 6.4 mg, 8.5 mg, and 15 mg.

- Adverse events: The most common side effects in the field trials include vomiting or nausea (22.1%), diarrhea (19.9%), lethargy (12.2%), and anorexia (9.4%). Other side effects worth mentioning include elevated liver enzymes (5.5%), urinary tract infection (5.5%), and leukopenia (4.9%).

- Warning: The manufacturer recommends discontinuing ilunocitinib 28 days to 3 months prior to vaccination and not giving ilunocitinib for at least 28 days after vaccination. This recommendation is based on the fact that a vaccine response study showed that dogs treated with ilunocitinib are at risk of fatal vaccine-induced disease from modified live virus vaccines and of inadequate immune response to any vaccine.

- Lokivetmab (Cytopoint®):

- Cytopoint® is a caninized monoclonal antibody against canine IL-31.

- IL-31 has been shown to cause pruritus in dogs when administered subcutaneously, intravenously or intradermally.

- Randomized controlled trials in client-owned dogs with atopic dermatitis showed that the subcutaneous administration of Cytopoint® at the dose of 2.0 mg/kg significantly reduced the pruritus associated with the disease within 1-3 days and subsequently improved skin lesions after 7 days. The effects can last for 3-8 weeks (most commonly 30 days).

- More than 80% of dogs have shown to benefit from this treatment modality. It is important to know that lokivetmab has minimum effect in reducing inflammation and that it works best if given proactively, in other words, before a disease flare occurs.

- If the first dose of Cytopoint® worked well but the second did not, increase the dose to 3-4 mg/kg and try two additional treatments. A few dogs may respond to this change in treatment protocol.

- Side effects: Most dogs tolerate Cytopoint® very well. The most common side effect is mild lethargy for a day or two after the injection. Vomiting and other gastrointestinal signs have been reported but these adverse effects are rare. Long-term side effects are not known.

- Some advantages of lokivetmab over the discussed immunomodulating drugs include no need for withdrawal before allergen testing, no drug interactions, improve compliance due to its long effect, and no risk for immunosuppression.

- Some dogs may experience loss of treatment efficacy after a few doses. The cause for the ensuing lack of response is unknown at this time but may be related to the development of neutralizing antibodies to lokivetmab

- Topical therapies:

- In general, topical therapy for patients with atopic dermatitis entails using various products that aim to moisturize the skin, reduce the inflammation and pruritic response, and repair the skin barrier. For more details regarding the use of topical therapies in the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis, refer to the review article by Santoro, 2019.

- Antiinflammatory and antipruritic agents:

- Glucocorticoids (GCs). GCs have excellent antiinflammatory and antipruritic effects. When used topically, GCs have less side effects but can cause skin atrophy and form comedones. Prolonged application on large skin areas can eventually lead to systemic absorption and cause iatrogenic Cushing’s disease. Many topical ointments and creams contain potent GCs such as triamcinolone acetonide, betamethasone, and dexamethasone. GCs in the form of diester like mometasone furoate, hydrocortisone aceponate and prednicarbate, have been developed with the goal of minimizing the side effects. Hydrocortisone aceponate and prednicarbate are metabolized in situ into inactive molecules, which eliminates or significantly reduces systemic signs. However, some degree of skin atrophy can occur with these GCs. Products in the form of shampoo and leave-on formulations containing 0.5-1% of hydrocortisone or 0.0584% hydrocortisone aceponate, can be effectively used as adjunctive therapy or sole therapy in mild disease. Products containing potent GCs such as triamcinolone acetonide, betamethasone, and dexamethasone should be ideally used to treat focal areas of severe inflammation and patients should be closely monitored for potential side effects.

- Calcineurin inhibitors. Tacrolimus 0.1% and 0.3% ointment have shown to effectively reduce the clinical signs of dogs with atopic dermatitis when applied to localized lesions. Mild skin irritation can occur. Because a fourfold increase in blood tacrolimus concentration was observed in the study investigating the 0.3% formulation, it is prudent to use the 0.1% ointment until more studies are done to refute this finding. A placebo-controlled trial showed that a nanotechnology formulation of cyclosporine significantly improved the clinical signs of dogs with atopic dermatitis compared to placebo, when used to treat localized moderate to severe lesions. More studies are needed to help determine the cost/benefit of using topical calcineurin inhibitors to treat focal lesions of atopic dermatitis in dogs.

- Local anesthetics. Pramoxine has been an active ingredient of shampoo and cream rinse formulations. Only one crossover open trial evaluated the effect of two pramoxine-containing cream rinses in dogs with atopic dermatitis treated for 4 weeks. Forty-one percent of pet owners judged the products effective in reducing pruritus and their effect lasted for two days. Blinded, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trials are needed to critically evaluate the effect of pramoxine in reducing pruritus in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Skin barrier-repairing agents. A few clinical trials have shown the benefit of using topical products containing essential oils, sphingosines, fatty acids, cholesterols and ceramides in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Commercially available formulations can have one or more of these ingredients. These studies have demonstrated the skin barrier-repairing and anti-inflammatory/-pruritic effects of some products. However, more randomized, placebo controlled clinical trials are needed to support their used as sole or adjunctive therapy in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

- Cyclosporine (Atopica®, Cyclavance® – microemulsion formulations):

-

-

-

-

H. Client Education:

-

-

- Clinical education is very important for a successful management of this chronic allergic disease.

- Pet owners need to know that like in people allergies in animals cannot be cured but can be controlled.

- It is very important that the pet owner understands that he/she have to be a partner in the treatment of this disease.

- Pet owners have to understand that multiple therapies may be need to control the pet’s allergic condition and the ultimate goal is to find the treatment regimen that controls well the disease with minimal side effects. However, it may take a while to achieve this goal.

- Dogs with atopic dermatitis are prone to develop bacterial skin infections and/or yeast and bacterial skin and ear overgrowth, which often aggravate the disease.

- Infections frequently recur and need to be treated properly; therefore, expect multiple recheck visits.

- Call immediately if at any time the disease flares.

-

Important Facts

- Treat every case as a single patient!

- Multi-modal therapy will be required to control the allergic condition in most cases.

- Remember to tell your client that atopic dermatitis cannot be cured but only controlled with continuous or intermittent therapy.

- Staphylococcal pyoderma, Malassezia dermatitis and seborrhea often aggravate the pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis. So, identify and treat them appropriately!

- The only mode to treat atopic dermatitis specifically is the allergen-specific immunotherapy.

- The success rate of allergen specific immunotherapy is about 60-70%. In general, response is not observed before 3 months of therapy, and may not occur until 9 to 12 months.

- Medical therapy should be instituted if the animal is not a candidate for allergen-specific immunotherapy, when waiting for the allergen-specific immunotherapy to work, or if the animal does not respond to allergen-specific immunotherapy.

- Medical therapy includes antihistamines, fatty acid supplements, corticosteroids, other immunomodulating drugs such as cyclosporine (Atopica®, Cyclavance®), oclacitinib (Apoquel®) and Lokivetmab (Cytopoint®).

- Topical therapy with the goal of moisturizing the skin, reducing the inflammation and pruritic response, and repairing the skin barrier are often used as adjunctive therapy in dogs with atopic dermatitis. These products come in various formulations containing a variety of active ingredients.

- Client education is essential for the successful treatment of atopic dermatitis.

References

Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of the Janus kinase inhibitor oclacitinib (Apoquel) in client-owned dogs with

atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2013; 24: 587–e142.

Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2013; 24: 479–e114.

Canning P, Brame B, Stefanovski D, et al. Multivariable analysis of the influence of cross-reactive carbohydrate determinant inhibition and other factors on intradermal and serological allergen test results: a prospective, multicentre study. Vet Dermatol 2021; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12974.

Favrot C, Steffan J, Seewald W, Picco F. A prospective study on the clinical features of chronic canine atopic dermatitis and its diagnosis. Vet Dermatol 2010; 21:23–31. Vet Dermatol 2020; 31: 365–e96.

Fischer NM, Rostaher A, Favrot C. A comparative study of subcutaneous, intralymphatic and sublingual immunotherapy for the long-term control of dogs with nonseasonal atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2020; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12860.

Foster S, Boegel A, Despa S, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of ilunocitinib and oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2025; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13319.

Gadeyne C, Little P, King VL, et al. Efficacy of oclacitinib (Apoquel) compared with prednisolone for the control of pruritus and clinical signs associated with allergic dermatitis in client-owned

dogs in Australia. Vet Dermatol 2014; 25: 512–e86.

Gedon NKJ, Boehm TMSA, Kinger CJ, et al. Agreement of serum allergen test results with unblocked and blocked IgE against cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) and intradermal test results in atopic dogs. Vet Dermatol 2019; 30:195-e61.

Gray AA, Hillier A, Coe LK, et al. The effect of ketoconazole on whole blood and skin ciclosporin concentrations in dogs. Vet Dermatol 2013; 24: 118–e28.

Hensel P, Santoro D, Favrot C, Hill P, Griffin C. Canine atopic dermatitis: detailed guidelines for diagnosis and allergen identification. BMC Vet Res 2015; 11:196.

Klotsman M, Anderson WH, Wyatt D, et al. Treatment of moderate-to-severe canine atopic dermatitis with modified-release mycophenolate (OKV-1001): A pilot open-label, single-arm multicentric clinical trial. Vet Dermatol 2024; DOI: 10.1111/vde.13283.

Little PR, King VL, Davis KR, et al. A blinded, randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of oclacitinib and ciclosporin for the control of atopic dermatitis in client-owned dogs. Vet Dermatol 2015; 26: 23–e8.

Marsella R, Doerr K, Gonzales A, et al. Oclacitinib 10 years later: lessons learned and directions for the future. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2023; doi.org/10.2460/javma.22.12.0570.

Marsella R, De Benedetto A. Atopic dermatitis in animals and people: an update and comparative review. Vet Sci. 2017; 4:37.

Marsella R., Nicklin C., Lopez J. Studies on the role of routes of allergen exposure in high IgE-producing beagle dogs sensitized to house dust mites. Vet Dermatol 2006; 17:306-312.

Michels GM, Ramsey DS, Walsh KF et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose determination trial of lokivetmab (ZTS-00103289), a caninized, anti-canine IL-31 monoclonal antibody in client owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2016; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12376.

Michels GM, Walsh KF, Kryda KA et al. A blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety of lokivetmab (ZTS-00103289), a caninized, anti-canine IL-31 monoclonal antibody in client owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2016; DOI: 10.1111/vde.12364.

Miller, Griffin, Campbell. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th Edition. In: Hypersensitivity Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013 p 365—388.

Olivry T., Banovic F. Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: time to revise strategy? Vet Dermatol 2019; 30:87-90.

Olivry T, DeBoer DJ, Favrot C, Jackson HA, Mueller RS, Nuttall T, et al. Treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: 2015 updated guidelines from the international committee on allergic diseases of animals (ICADA). BMC Vet Res 2015; 11:210.

Olivry T, Foster AP, Mueller RS, McEwan NA, Chesney C, Williams HC. Interventions for atopic dermatitis in dogs: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Vet Dermatol 2010; 21:4–22.

Piccione ML, DeBoer DJ. Serum IgE against cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCD) in healthy and atopic dogs. Vet Dermatol 2019; 30: 507-e153

Plant JD, Neradilek MB. Effectiveness of regionally-specific immunotherapy for the management of canine atopic dermatitis. BMC Vet Res 2017; 13: 4. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0917-z

Reedy, Miller, Willemse: Urticaria, Angioedema, and Atopy. In: Allergic Skin Diseases of Dogs and Cats, 2nd ed, W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1997, p 33 – 49.

Santoro D. Therapies in canine atopic dermatitis: an update. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2019; 49:9-26.

Scott, Miller, Griffin: Immunologic Skin Diseases. In: Small Animal Dermatology, 5th ed, W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1995, p 500 – 518.

Timm K, Mueller RS, Nett-Mettler CS. Long-term effects of intralymphatic immunotherapy (ILIT) on canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2018; 29:123-e49.

Umstead ME et al. Accuracy and precision of compounded ciclosporin capsules and solution. Vet Dermatol, 2012; 23: 431-439.